These are the show notes to an audio episode. You can listen to the show audio by clicking here: http://traffic.libsyn.com/airspeed/AirspeedGliderRating2.mp3. Better yet, subscribe to Airspeed through iTunes or your other favorite podcatcher. It’s all free!

This is the second part of a two-part series covering my glider rating. To bring you up to speed, in March of this year, I began training in the TG-7A motorglider to add a glider rating. In May, I soloed the aircraft for the first time. Part 1 covered events up through the solo. On to Part 2.

After the solo, things move more quickly. You’ve proven that you can operate the aircraft without the instructor aboard. Or at least that you’re so lucky that you don’t need the instructor. Same result.

Now it’s all about the checkride. It’s not as though you haven’t been preparing for the checkride since your very first flight. But now is when you think about it a lot more.

I bought Bob Wander’s commercial checkride guide. I borrowed some of John’s Harte’s materials. I looked (briefly) for commercial glider knowledge test prep software or online courses, but that was futile. I can perhaps forgive Gleim and the other test prep companies for not having a course tailored for commercial glider guys. We can’t be much of a market. So I paid for Gleim’s regular airplane commercial pilot ground school. It’s geared toward airplane pilots, but the regulatory review was bound to be helpful and I’ll probably go after the commercial for ASEL and AMEL soon anyway.

John and I started hitting the training once a week or so, usually first thing in the morning at the crack of dawn. Sunrise was coming earlier and earlier and we made it a point to turn the prop as soon after sunrise as possible on each of those flights. Mostly, we explored other parts of the glider PTS. We did stalls and slow flight and went looking for crosswinds to work on that technique.

One morning, we headed down to Grosse Isle (KONZ) and beat up the pattern hard. If there’s a more beautiful airport at which to do pattern work just after sunrise, I don’t know which one it might be. Plus, if you work your pattern just right, you can stick a wing into Canada on the downwind for Runway 4/22.

We worked on no-spoiler landings and using slips to get the glider down.

Quick technical note: Most or all gliders are equipped with some kind of drag and/or lift-spilling devices. If they’re on top of the wings, they’re usually spoilers. If they’re on the bottom of the wings, they’re usually dive brakes. The TG-71 has both and they’re both operated by the brake handle to the pilot’s left.

Heck, some gliders even have flaps. But, when glider pilots in my community talk about landing without these devices, the usually lump all such devices together and call such landings “no-spoiler” landings. Just wanted to get that laid out before you headed to the comment section of the show notes to needle me. In any case, your hate mail will be graded.

Gliders are slippery, slippery things if you don’t use spoilers. They don’t like to get down and stopped without spoilers. They are, after all, gliders. Remember when you first learned about ground effect? And you learned that ground effect usually exists within a wingspan of the ground? Think about the wingspan of a glider. That’s a pretty deep region above the runway. And I can tell you from personal experience that, when the induced drag gets reduced to nearly zero, the aircraft just wants to go forever.

You as a glider pilot need to be able to get the aircraft down and stopped if your spoilers don’t work. They could get stuck or you might end up with only one side working and you’d need to land with the spoilers put away.

If you get into this situation, you have only a couple of tools in your tool kit. One is to get as slow as you can before crossing the runway threshold. Each additional knot of excess airspeed adds to your float in an exponential (or at least definitely not linear) way.

The other option is to slip. I’m certainly used to slips in airplanes. I have no problem rolling out on final, judging the altitude, putting the downwind pedal on the floor, and feeding in upwind aileron to coordinate until I’m ready to straighten it out and land normally. But the glider guys take it a little further. Whereas I generally don’t slip airplanes until I’m on final and it’s a true forward slip, the glider guys slip it all the way around the corner from downwind to final, keeping a close eye on airspeed to both avoid building up speed and to avoid stalling on the base-to-final turn at low altitude with nearly full-cross-controlled inputs.

John started out by taking away my spoilers and having me land normally. I came in way too fast and ended up floating down nearly the entire length of the runway at three feet AGL or so. We ended up going around because there’s no way that I could have made the end of the runway.

The next time around, in right traffic, we hung it out a little further on downwind, then John had me put the left pedal all the way to the floor and make a big, sweeping right turn to final. It takes an amazing amount of pull to keep the nose up and the airspeed down. You’re watching the runway slip under the nose and you want like heck to point the nose at it, but, if you do that, you’re going to put on an extra 20 mph of airspeed in a hurry and destroy your chances of getting a decent landing out of it.

I did that a couple of times. We kept the slip control inputs in even in ground effect. It’s really weird to be there with the gear three feet off the ground with the nose pointed 30 degrees off centerline and waiting for the lift to bleed off. I managed to get it down each of those times, but not with enough runway remaining to make a touch-and-go out of it. On those occasions, we just took off downwind and did a 180 abort to get turned back around, then launched upwind to do another no-spoiler landing.

This is one of those areas of training in which I managed to get it right a couple of times purely by mistake. I got the result, but didn’t fully understand how I had done it. Not in a repeatable way that would put the technique squarely in my tool box. Thus, I fooled John and myself into thinking that I had the maneuver down. This becomes important later in ways that I’m sure you can already imagine.

We also talked a lot about glider operations. Any glider DPE is almost certainly going to come from the aerotow or ground launch worlds and, in any case, his or her allegiance is very likely going to be to aircraft that keep their motors in other aircraft. Accordingly, the oral is going to have some aero-tow and ground launch content in it.

We talked through aero-tow procedures. We talked about the two main kinds of releases and hardware. He lent me a Tost ring set to carry as a good-luck talisman.

The requirements to add on a glider rating to a private certificate are pretty basic. A certain amount of training, 10 solo flights (which I already had under my belt), the endorsement, the knowledge test, and the ability to pass the checkride.

John had said something during the training about the commercial PTS being not a lot different from the private PTS. The only addition is an accuracy landing, which, with an engine and wheel brakes, in addition to spoilers, seemed like cheating. In exchange, the standards for the stalls get diluted. You only have to go to the first indication of a stall, instead of going into full stall. If you’ve listened to Part 1 of this piece, you know about the history of this aircraft in stall-spin situations, including the amorts at the academy. The rule in the flight manual is no bank below 75 mph. I had stalled the TG-7A several times in level flight and had no problem with the procedure or the recovery. But I wasn’t nuts about stalling it in a turn, as required by the PTS. The ability to recover early from the turning stall seemed to be a more than fair tradeoff.

Truth be told, I have the IP supplement to the Air Force technical order and academy IPs were required to go out every so often and spin their lips off in the TG-7A. So I know that one can do it and that the aircraft itself is fully functional for the checkride. I’m also pretty sure that, with enough altitude, I could recover the thing. I just didn’t want to do it if I didn’t have to.

Of course, going for the commercial certificate meant that I’d have to take a commercial written exam (no additional knowledge exam is required for a private add-on) and that I’d have to go through a much more comprehensive oral. Sure, it’d be a time-suck, but written and oral exams have never really bothered me. I can knock them out pretty easily and I was going to have to take and pass a knowledge test for my power commercial certificate anyway.

Plus, although I didn’t spend any time researching it, it wouldn’t surprise me if doing my ASEL and AMEL as add-ons to an existing commercial certificate turns out to be easier in some respect.

A few flights later, John signed off my logbook for the knowledge test and thus kicked off the running game for the checkride. I used that most powerful of tools: The deadline.

The Tuskegee Airmen Flight Demo Team was heading to Battle Creek for the Battle Creek Field of Flight Airshow and Balloon Festival and all three aircraft were therefore going to be on the ramp all weekend. My uncle, a Viet Nam -era air cavalry pilot, lives in town and I really wanted to be able to give him a ride. If I could knock out the checkride before Battle Creek, I could do it. Plus, the idea of having aircraft on the flight line at an airshow that I could climb into and go fly whenever the box wasn’t hot was practically irresistible.

(Think about that for a minute. You’re at an airshow. And you can walk onto the performer ramp, grab one of the airshow aircraft, and go fly it. If you don’t have chills going up your spine right now, we can’t be friends.)

So I scheduled the checkride on the Tuesday before the show. And I committed to passing the knowledge test before the end of the preceding weekend.

There are several points in this episode where I’ll say nice things about Kerry Brown, an FAA designated examiner working out of the Michigan East FSDO. Apparently, it’s pretty common for pilots and pilot candidates to schedule checkrides and then call them off at the last minute or not show up at all. Thus, a guy like Kerry could be forgiven for insisting on some indicia of preparedness before scheduling a checkride. And Kerry didn’t know me from a stack of hay. But he agreed to schedule the checkride even though I didn’t have the knowledge test complete and wouldn’t have it complete until a couple of days before the ride.

Thursday of the week before the checkride, I went down to the Tuskegee hangar to meet with John and with Mark Grant. John signed me off for the knowledge test. I also went through the maintenance records for N26AF, the aircraft that I’d be flying to make sure that I could walk Kerry through them during the oral.

I studied through Saturday and Sunday morning, then went to Pontiac Air Center and took the knowledge test. I scored something like a 93%. Not as good as some, but about my average for an FAA knowledge test. A high enough score to show the examiner that I’m walking in with a good handle on the information but not so high that I’ve wasted time on the knowledge test that I could have spent doing other checkride prep.

When I got home Sunday night, I began preparing for the checkride itself. Getting all of the manuals together, making my folders, and things like that. Just for giggles, I pulled out the FAR and went through the requirements for the commercial glider certificate. I knew that the PTS was very similar to the private PTS, but it had been gnawing at the back of my mind that I hadn’t checked out the experience and other prerequisites. Walking through the requirements, I realized that I needed 20 – not 10 – solo glider flights. It was already 10:00 at night by that time, but I dialed up John and we both verified that that was the case. I think that I was the first of John’s students to go straight to commercial as the ab initio certificate in the glider category, so no flies on John. And, besides, I’m an experienced pilot and a lawyer to boot, so I should have caught that.

The museum’s insurance requires that an instructor be present for all student solos. So we made arrangements to meet at the airport at sunrise. I turned the prop as soon as John arrived and banged out 10 takeoffs and landings. Then I got in the car and headed for Ann Arbor.

I had realized earlier in June that I was due for a flight review by the end of the month. And, for that matter, I had flown the gliders so much that I was actually out of currency to carry passengers in airplanes. I hate not being current to exercise all of the privileges of my certificates and ratings. You work hard for them in the first place and, even if you’re not actually using them to go places, you still want to be current. You never know when you might have the chance to fly something and you sure as heck don’t want to have to turn down an opportunity if it arises.

In truth, I was planning on the new commercial certificate to take the place of the flight review. In fact, that’s my favorite way to stave off a flight review. Not that I have any aversion to flight reviews. I have to do a CAP Form 5 every year anyway. But it says something about you when you add new certificates or ratings. And I like what it says.

Earlier in the month, I had flown Solo Aviation’s DA-20 with Nick Demski, who, it turns out, is a listener. (Hi, Nick!) We got more than an hour in the air and I suggested that we turn the time into a flight review. Nick didn’t have adequate time to get the ground portion of the flight review done on the day we flew, so I had arranged to go in and do the hour on the ground on that Monday.

I have nothing but respect for a CFI who endures a flight review with a guy who just passed his commercial knowledge test and who is absolutely wired for his commercial checkride. I don’t even remember much of what Nick talked about. By the time any question was halfway out of his mouth, I was blurting out an answer. I’m not even sure that the answer was intelligible. But I was in blurt mode and drooling-ready to get the checkride over with. So Nick barely had a chance to talk during the flight review. I still feel kind of bad about that.

But Nick did fill me in on what subjects were on the FSDO’s mind. Oddly enough, that included avoiding guy wires on tall antennas. I guess that there’s been a rash of aircraft getting wrapped up in antenna guy wires. Who knew?

So I had a fresh flight review and I was good to go in airplanes for another two years. Could I have used that time more profitably preparing for the checkride? Sure. But such is the tortured calculus of a ratings and currency whore.

*****

Tuesday dawned with perfect weather for a checkride. Kerry was going to meet me at Livingston County Airport (KOZW) in Howell for the ride at 0900L. John had offered to go with me for some last-minute warm-up. We turned the prop at around 0730L and skirted the Detroit Bravo airspace before pointing the nose at Howell.

On the way over, I did some air work. A couple of full 360s at different airspeeds and bank angles to get an idea of how much altitude I’d burn and useful information when setting up for an emergency landing pattern or “ELP.”

I shut down the engine at altitude a few miles north of the field and spent some time in true glider mode. I also wanted to practice the shutdown and restart procedures. This turned out to be a good thing. I figured out where the restart checklist was among the emergency procedures and made a mental note to have that part of the flip book cued up before putting the checklist away after the climb and cruise checklist. We turned toward the airport and I went through the restart checklist. When I turned the key, the starter engaged and the prop turned, but no restart. John suggested a couple of shots of prime. I gave the plunger a couple of strokes and locked it back in place, then tried the key again. The engine turned over and we proceeded inbound.

Once in the pattern, I did a few trips around, just practicing straightforward landings. Simple stuff to get in the groove and give myself a few successful maneuvers to boost my confidence. After a few landings, we taxied in, shut down, and pushed the aircraft back so the tailwheel was in the grass. I visually checked the fuel and oil, then pulled the logbooks and other materials out of the back.

Kerry was waiting at the fence and greeted us warmly. We headed in to the terminal building.

We started upstairs where the WiFi reception was good, checked my IACRA application, verified my credentials, and made sure that the logbook endorsements were correct. Then Kerry and I left John in the lounge and went to the meeting room downstairs to do the oral.

I spread out the engine and airframe logbooks, my own logbook, a FAR/AIM, my iPad, and several other references on the table. I popped open a Diet Coke and bade the oral begin.

The oral lasted three hours. The first hour or so was verification of my credentials, going over my logbook, and walking through the aircraft logbooks. The rest was refreshingly practical in its approach. Kerry didn’t ask a lot of pure information questions. He might spread out a sectional chart and ask me about a flight from this airport to that airport and ask me to talk about what airspace we’d fly through, how I’d keep us safe, and how I’d find the destination or alternate airports.

We walked out to the aircraft. It was warm outside, but not too warm, and Kerry told me to do my preflight inspection. He climbed into the aircraft and strapped in. I took my time and did a thorough preflight, checking the oil, visually verifying the quantity of gas, and generally making sure that the bird was fit to fly. Having already operated the aircraft for awhile that morning, I wasn’t especially worried about airworthiness. This preflight was mostly cursory, although it included all of the checklist items and I made sure that I demonstrated to Kerry that I knew what I was doing.

I did the preflight from memory as a counterclockwise flow around the aircraft. Then I stood at the nose with the checklist and verified that I had completed every item. One last walk around looking for macro items. Rod Rakic likes to call it his “last, best chance” inspection and I think that it makes sense to do that.

Y’know. For tow bars.

I climbed into the right seat and strapped in. I offered Kerry the chance to read the checklists, not because I thought that he’d take me up on the offer, but to show him that I valued CRM and that I was willing to use even a putatively non-pilot passenger to best advantage if it would help with the efficiency and safety of flight.

I dutifully went through the checklist. I won’t spoil Kerry’s routine by telling you exactly what he did, but he futzed with one item in the cockpit while I was outside preflighting and I noticed it. I probably wouldn’t have noticed it if I hadn’t used the checklist and used both visual and tactile senses. I did ask him whether he had futzed with the thing and he answered in the affirmative. It was the kind of thing about which you’d think twice before flying if you didn’t know that the check airman had futzed with it.

We had briefed the flight to include launching to the south, doing the airwork, and then coming back in for the landings. The airwork would consist largely of steep turns, stalls, and other basic airmanship, as well as shutting down the engine, maneuvering while in true glider mode, and then restarting the engine to return to the airport for the landings. The landings would include a no-spoiler landing, an emergency landing, an accuracy landing, and a 180-abort from 350 AGL.

The 180 abort is to a standard traffic pattern as a turd is to a punchbowl, so we discussed the possibility of doing the 180 abort whenever the pattern was the least busy – on the first takeoff if need be.

Start-up and taxi were normal. I did my run-up and then took off on Runway 31. There was at least one aircraft in the pattern, so we elected to just head out and do the airwork and save the 180 abort for later. Heck, I’m spring-loaded for the 180 abort on every takeoff, so he could have decided to spring it on me on the initial takeoff and it wouldn’t have mattered. And I guess it’s a little difficult to surprise a guy with a 180 abort at anything other than a glider field. At a regular GA airport, you probably want to announce on the radio what you’re doing and it’s hard to announce a 180 abort on the radio without the guy in the other seat hearing it.

Power up with stick back, let the stick come forward and let the tail come up. Helicopeter along in ground effect to 68 mph. Climb out. Cheat downwind. Be prepared to abort upwind. Straight, straight, straight. 350 AGL. Abort possible. Continue climb.

A left turn took us south of I-96 and soon we were six or seven miles south of the airport at three or four thousand feet. I did the high airwork first.

Steep turns went fine. To be honest, I didn’t know whether the TG-7A would maintain altitude with 45 degrees of bank at that density altitude, so I had pre-briefed with Kerry that I’d hold altitude if I could do so and maintain 80 mph of airspeed. If I couldn’t keep the altitude at 80, we’d descend at whatever rate maintained the 80 knots in the turn. I guess I needn’t have worried. If anything, I climbed. In fact, I was a little disappointed in my altitude tolerance for the maneuver. Not something that I would have been proud of in an airplane.

We did the slow flight and stalls. The straight-ahead stall was fine. In the turning stall, I entered the proper attitude in a measured, efficient, and graceful way. Then I recovered as soon as I felt the controls get genuinely soft. “First indication of a stall” and all. I’m pretty sure that I got some stall horn, too, but I gauged the recovery based on control effectiveness. After all, that’s a much better indicator of what’s going on aerodynamically. I felt a little sheepish and asked Kerry whether he wanted me to take it deeper, but he said that he was satisfied with the stalls, so I shut up.

Kerry told me to shut down the engine. I pulled the throttle to idle and began bringing the nose up to bleed off airspeed. Carb heat on. Throttle to idle. Verify fuel pump off. Pull mix to idle. Slow the aircraft to best glide, which is between 59 and 62 mph. I shot for 60 mph. The engine shut down and the prop came to a stop. Mags off. Carb heat off, throttle to halfway, and mix to full rich in anticipation of restart.

I held the aircraft at the proper airspeed on a heading. Kerry assigned several turns. Each time, I let the nose come down and got 75 mph of airspeed before turning to the assigned heading and pitching back up for best glide.

Kerry asked what speed I should fly if I was heading back to the airport. The wind was generally on the nose in the direction of the airport at around 10 knots, So I answered with the best glide speed plus half of the headwind.

Satisfied, Kerry told me to restart the engine. I had the checklist ready to go. Primer locked. Fuel pump on. Starter. Blades pass in front of the windshield. But no noise. Hmmmm.

Now, we’re right over two private grass strips. Cloud Nine East and West. We’ve got a place to land and plenty of altitude. And if it all goes to crap, I’ve still trained for this and I’ve got a guy in the left seat who is well motivated to avoid death or dismemberment even if his intervention means a discontinued checkride. So I’m pretty calm.

I reach over and give her two shots of prime. Then starter again. And my favorite noise in the world wells up from the nose of the aircraft. Yeah, baby!

We head back to the airport to do the landings. The first one is the no-spoiler landing. Howell’s 5,000-foot runway is intersected by two taxiways at roughly even intervals. Kerry tells me that there’s an imaginary fence crossing the runway at the second taxiway and I need to get her down and stopped prior to that imaginary fence. That’s essentially fair. In an emergency situation, a commercial glider pilot ought to be able to get a glider down and stopped in the 3,500 or so feet represented by that much runway.

I make all of the appropriate radio calls and get onto the downwind. Kerry informs me that the spoilers are not functioning and that I need to make a no-spoiler landing. I hang it out on downwind a little longer than usual, then pull carb heat, turn on the fuel pump, pull the throttle to idle, and turn base.

I suppose that I should have sensed the gasp of horror that Kerry was emitting over there in the left seat. I got lucky on the last few no-spoiler landings that John and I had done weeks ago and now it was going to come back and haunt me.

I put the right rudder all the way to the floor and kept the turn coming. I let the nose get low and we picked up a bunch of airspeed. Not good. I pulled back up and the airspeed decreased, but I wasn’t descending. I’m maybe a quarter mile out and still at 500 feet. And every thermal in Livingston county converged there on the numbers and shot straight up under my wings. At one point, I was completely cross-controlled at 80 mph and actually climbing.

Somehow, I got her down into ground effect about halfway down the runway.

I’ve commented before on the shortcomings of the TG-7A as a glider. Even basic gliders tend to have glide ratios that begin around 30:1 and some of the high-performance models out there push or exceed 70:1. The TG-7A has a 19:1 glide ratio, about the same as the state of the art in the gliders of the 1930s. The “Gimli Glider,” the Boeing 767 that ran out of fuel mid-flight and landed in Gimli, Manitoba, had a glide ratio of 12:1.

But, in ground effect, the TG-7A becomes a greased lemming on crack. It is a weightless, superconducting, pan-dimensional floating yellow banshee that will not land. At that point, all I could do was hold the control inputs and watch. At last, I was afraid that we’d land sideways and blow a tire, so I straightened her out. She touched down in a three-point attitude about 100 feet short of the taxiway.

At that point, I had a decision to make. I know that I could have stopped the aircraft by slamming on the brakes with full aft stick. I would have flat-spotted the tires, made a horrible noise, and cast off any aesthetic points, but I could have gotten it stopped. $200 in new tires? No problem.

But the cost would have been a lot greater than that. If I had done that, I might have satisfied the technical requirements for the maneuver. And I probably would have aced the remaining landings. But, even if I had technically met the PTS by doing that, did I really want Kerry to be sitting there with doubts in his mind about the capabilities of this commercial candidate?

Nope. That’s not the right way to do it. So I let it roll with only normal brake pressure.

Kerry’s voice came over the intercom, as I knew it would. “Steve, I’m terribly sorry, but I have to discontinue the practical test.”

Yep. Ladies and gentlemen, Stephen Force hooked his checkride.

We taxied back to the ramp. John was waiting at the fence. And apparently making hand-shaped indentations in it. He had seen the early turn to base from downwind. I dragged in to the terminal building, Kerry logged on to IACRA and generated the paperwork, and we debriefed. Kerry seemed at least as blue as I was about the hooked ride. And I was pretty blue.

John and I gassed up and climbed back into the aircraft. We did a couple of takeoffs and landings there at Howell and a couple more back at Detroit City before John had to head out to an appointment. I buttoned up the aircraft and headed home.

I take at least some credit for starting or popularizing several aviation expressions and memes. My Friday kicking your Friday’s ass. The #HaveTheFish hashtag. And a couple of others. One of those others is that it’s not a problem to hook a checkride. Of course you want to pass every one of them. But it’s not a problem to hook a ride because the penalty is that – wait for it – you have to fly more. And, after all, isn’t that what it’s all about? Oh, please don’t throw me in that briar patch!

Now I had a chance to see if I was willing to eat crow in the unabashed way that I’d been promoting to my audience for years. “Hey, check out this crow! Yeah! Crow! It’s got some nice basil and lemon on it. Man, you ought to check out this crow!”

As soon as I got home, I posted to Twitter and Facebook that I had hooked the ride. I got the expected expressions of sympathy and solidarity. Those expressions helped. But I would much rather have passed the checkride.

I went to the Battle Creek show with the team later in the week. I still had a solo endorsement in the aircraft, so I could still fly the thing around solo or with a CFIG. But not with anyone else. And definitely not Uncle Denny.

The Battle Creek show this year was pretty cool for a number of reasons – even beyond the usual reasons that it’s cool. That’ll be the subject of another upcoming episode.

On the way home from Battle Creek that Sunday, I picked up Don Weaver from Jackson and drove him to Ray Community Airport (57D), overshooting home by about an hour. I helped Don load up the Pitts and I loaded up my car with the Pitts road support stuff that wouldn’t fit in my car. Don took off shortly after that to fly the Pitts to Jackson for the Michigan Aerobatic Open. I joined him back in Jackson Monday night and basically spent the week there training for, and participating in, the contest. I couldn’t quite get the Sportsman routine down well enough to bring it back from the practice area into the box, so I flew primary again. I took second, again, but flew much better than the previous year.

Then back to real life to take care of clients, prep for Oshkosh, and do laundry, and attend to the Clark Kent-y obligations of a minor media superhero.

I scheduled the second attempt at the checkride for Thursday, July 12. That morning, the alarm went off around 0430L and I got to the airport before sunrise to preflight and stomp the ramp a little.

I had a surprise for John. I usually run at least one video camera on each flight, and sometimes run as many as four. In reviewing the footage from our first few flights, I noticed that John gestured a lot with his hands as he talked. I hadn’t noticed that while flying because I was pretty focused outside the aircraft or looking at the gages. I mentioned it to John and it became a bit of a running joke. I suggested at one point that I should get John a couple of sock puppets and they could have a running conversation about my flying.

“Oh, have you looked at this airspeed indicator over here?”

“No! What does it say?”

“It says Steve is trying to kill us!”

“Oh no! Why, oh why, do they let him fly this thing?”

Six weeks or so before the first try at the checkride, I found a place online that made custom sock puppets to look like specific people. You send them pictures and some money and they send you a sock puppet.

A day or two before the second checkride, the John sock puppet arrived. It was pretty amazing. Gray pony tail, a goatee, glasses, and even a little David Clark headset that Velcros to the puppet’s ears. As John drove up, I donned the puppet and, as he walked up to the aircraft, I greeted him in the puppet’s voice.

A guy could be forgiven if he took a sock puppet the wrong way. Fortunately, John warmed immediately to his Mini-Me.

We loaded up, turned the prop, and took off, climbing to 3,500, planning to skirt the northern edge of the Class B where it comes down to 3,000. I called Detroit Approach to ask for flight following to Howell and was pleasantly surprised to be cleared into the Bravo direct. The puppet commented as well, but we kept him off the radio.

We got to Howell plenty early. Most of the next hour turned into a tutorial on no-spoiler landings. The wind favored 13, so we beat up 13 pretty heavily. We started out by figuring out how far downwind I’d have to fly before turning base in order to arrive at the numbers on speed without slipping substantially. It turned out to be about two miles. If you’re following along on Google Maps, we didn’t turn base until just short of the lake east of Fleming Cemetery.

The outer limit thus having been determined, we began turning sooner and experimenting with varying amounts of slipping. By the time we were done, I was pulling the throttle a little under a mile past the numbers, flooring the right rudder, and swooping gracefully around onto final. Once on final, I rolled out and let off the rudder. I eyeballed my altitude and the distance to the threshold and, if I had too much energy and/or altitude, I slipped it some more and then rolled out to check again.

By the time we finished the no-spoiler session, I was at the right energy state when I needed to be there, at about 70 mph with the wheels dragging pretty close to the rabbit lights. She still wanted to float like hell and roll like crazy, but I nailed three or four landings well before the second turnoff.

We also did a couple of accuracy landings. It felt pretty good to have the spoilers back for those. I really felt like I was in control of the aircraft again. I paid attention to the aim point, touchdown point, and roll on each of those. I figured that, in a motorglider, as long as you’ve got your engine, you can always land short and goose the throttle a little if you need a little juice to get up to the near part of the stop zone. But I paid attention to the pure kinetics without the engine just for the heck of it.

We finished up with a couple of 180 aborts – one from each end of the runway – then taxied in to the ramp.

Kerry was there and ready to go. John made a show of the sock puppet. Kerry was decidedly less excited about the puppet than John and I were. But that’s okay. Slightly deranged-looking sock puppets with pony tails and Velcro headsets aren’t for everyone.

We sat down and did the paperwork and then briefed the flight. He explained that he could, at his discretion, require me to fly the entire ride again. I responded that I was ready to do so if required. He said that he was only going to require the areas of operation that I had failed. Which was nice of him.

That meant that the re-test was going to happen entirely at the airport. I needed to perform a 180 abort, a no-spoiler landing, the accuracy landing, and an emergency landing without the altimeters.

All good, but there was one wrinkle that I had not counted on. We were going to do the accuracy landing engine-off.

Okay, not what I was expecting, but I’ve got this. I’m primarily a power guy. I rarely shut down the engine in flight. But the best glide speed for the aircraft is within three mph engine windmilling vs. engine off and I land with the engine windmilling from downwind abeam all the time. The only issue was going to be making really sure that I had the accuracy part down.

Kerry and I strapped in and fired up. I stuffed the sock puppet in the back, just to have it along for the ride.

The wind still favored 13, so we taxied down to the end and ran up. We listened to the CTAF on the way down and we seemed to have the pattern to ourselves and only an inbound instructional flight ten miles out. Kerry suggested that we get the 180 abort done while there was nobody around. I agreed and taxied out onto the runway.

I made the call on the CTAF and fully described what I had in mind. Most power GA pilots have never seen a glider 180 abort. So I wanted to be sure that anyone on the frequency was aware of what to expect, namely a yellow longwing charging down the runway, climbing to 350 AGL, then abruptly pulling around at a 45 degree bank and landing downwind on 31.

The inbound instructional flight responded that it understood and that it would give me plenty of room. Pre-takeoff checklist complete, I stowed the spoilers and throttled up. Stick in my gut for a few seconds, let it forward and let the tail come up, then helicopter up into ground effect. Capture 68 mph and ride it up. The wind was slightly from the right, so I cheated left and announced that while also counting up the aptitude to a little over 1,300 feet MSL.

Passing 1,300 MSL, I pulled the carb heat, checked the fuel pump, pulled the throttle, and pushed smoothly but firmly for 80 mph.

Once the altimeter needle was well and truly in the neighborhood of 80 (there’s a lag, so at about 75 on a push like that, you can be reasonably assured of being a couple of seconds away from 80), I buried the right wing down to 45 degrees and coordinated with rudder. Pull, pull, pull. Pirouette the aircraft around that right wingtip. Runway in sight. Once lined up on the touchdown zone markers from maybe 30 degrees off-centerline, I rolled back to level.

And promptly deployed the spoilers, put the right rudder on the floor, and slipped like hell. We had gotten to 350 AGL a lot faster than I had anticipated and the amount of available runway staring at me was a lot less than I had expected.

I guess I needn’t have worried. I held her at 80 and she came gracefully out of the sky. And I put her down gently in a three-point attitude. Part of my reaction might have been the fact that the sight picture there above 31, high and trying to get down, was very similar to the signt picture that I had on the no-spoiler landing on the first attempt at the checkride. In any case, I was down safely and the checkride was still going. We turned off and taxied back to the approach end of 13.

Being that one of the next two landings was going to be engine-off and that Kerry would have to give me enough warning to actually shut it down, there was no point in waiting to tell me the next task. “Okay, take off and show me a no-spoiler landing.”

The other aircraft did a touch-and-go and we took off after it. The other aircraft was a Cessna 172 that could easily beat us around the pattern. I announced my intention to fly a 747 pattern from an extended downwind to base and final and the 172 indicated that that would be no problem.

The thought crossed my mind that I was about to perform the maneuver that I had blown the last time, but then I was all focus on the task at hand. The 172 was on short final. About half a mile past the numbers downwind, I pulled the carb heat, verified that the fuel pump was on, and then pulled the throttle.

Right foot on the floor, and a big, sweeping left turn toward the runway. The airspeed was painted on 80 and I held it there. The runway swung slowly from left to right in the windshield. I heard the 172 announce that it was touch-and-go and I spotted it on upwind.

Roll out on final. A little high. Back into the slip. Pop back out. Take another look. A quarter mile out. Looking good. And airspeed was down to about 70. It decayed to 65 as we made the threshold, dragging the wheels low over the lights.

Once into ground effect, I flared and waited to settle. The second taxiway and the imaginary fence seemed to race toward me. Shades of the last time trying to do this. We were in ground effect about three feet off. I put it into a slip again, or as much so as I could do without scraping a wingtip. I uttered unpleasant words.

Then “Doink.” The left main touched and we bounced off it. Because of the slip, there was a lot of side load. But I knew that the aircraft’s legs were now long enough to reach the ground, so I held it in a normal landing attitude and, a couple of moments later, we touched down with maybe two hundred feet left to go.

Kerry said that he was satisfied and that I didn’t have to brake – rather, I could just use the energy to roll onto the taxiway to head back to the approach end.

Okay. Last element. Engine-off accuracy landing. Kerry said that I could use either turnoff as the stop point. Whichever one I chose, I’d need to bring the aircraft to a stop within the 100 feet of runway immediately prior to the taxiway. I chose the second taxiway so that I could play with the middle part of the runway length, making the first taxiway my aim point.

We let the 172 take off ahead of us and I announced my intentions on the CTAF. We were going to climb to 1,500 AGL on the downwind, shut it down, and bring it in as a true glider.

We took off and headed for downwind abeam. I did a 360 to the right on downwind to make sure that I had 1,500 AGL made, then rolled out downwind abeam. I kept the stick back to start bleeding off airspeed. With the airspeed coming down nicely, I shut off the fuel pump and pulled the mix. A few seconds later, the engine obligingly quit.

Heading for about 60 mph of airspeed, I quickly reconfigured the panel for a restart in case it became necessary, then turned to the task at hand. The prop quit windmilling and stopped, sticking up diagonally in the windshield.

Kerry said, “Okay, get us down and don’t kill us.” Kinda matched my internal monologue, actually.

With the prop stopped, I let the nose down and pitched for 75 mph and turned base. I popped the brakes out of detent and let them ride close to the wings. This was my throttle now. Everything looked good and I made my turn to final, then aimed for the first intersection. Down the slide at 80.

I didn’t need to change much about the aircraft’s configuration. I was on speed and on glideslope the whole way with the intersection motionless in the windshield. At maybe 50 feet off, I pulled the brakes out a little more, then fully deployed them. Flare into the three-point attitude, and then hold it there.

The aircraft touched down with a few hundred feet to go to the beginning of the stop zone. I pulled the stick all the way back to get the tailwheel down and complete the transition to ground ops. Then I immediately stowed the dive brakes and pushed the tailwheel back off the ground to maximize the roll. It became apparent pretty quickly that I was going to roll right into the stop zone and perhaps even stop her without touching the brakes.

Kerry said, “Congratulations! You’re a commercial glider pilot. As long as you can taxi back without hitting anything . . .”

When we stopped, I quickly shut down the avionics, re-started the engine, then turned the radio back on and announced the taxi-off and thanked the 172 for the accommodations in the pattern.

We taxied in and gave John the good news. Kerry averred that it was true, but suggested that the puppet had not completed the ride with us. Sock-John was, of course, still in the back, but I played along with the storyline.

Pictures of the three of us by the aircraft and juch shaking of hands and slapping of backs. We went inside and Kerry logged back in to IACRA and printed out my new temporary airman certificate. It read:

Commercial Pilot: Glider; Private Privileges: Airplane Single Engine Land & Sea; Airplane Multi-Engine Land, Instrument Airplane; DC-3 (SIC)

He signed my logbook, too, and hung around while we gassed up the bird and then we said our goodbyes.

The flight back to Detroit was uneventful. Mid-morning, there’s no real possibility of the Bravo transition, so we just kept it at 2,500 under the 3,000-foot shelf and made a yellow streak for the airport. John had meetings, so I cut him loose, then put the aircraft to bed. And, as is my custom, I spend maybe an hour just walking around the hangar or standing on the ramp, decompressing and trying on the sound of the new certificate and rating for size.

*****

If you had told me in March that I’d be a commercial glider driver in July, I probably would have chuckled at you. Generally speaking, a commercial glider certificate and rating is almost perfectly useless. I can fly rubber dog poop out of Hong Kong for money, as long as you don’t need me to move more than 196 pounds of it at a time and I can refuel every two hours.

But I’ve had a lot of fun with it. As I write this in November, I have something like 65 hours in the TG-7A. I’ve flown three Young Eagles and I’ve flown my sister, my son, and my daughter. I took fellow CAP officer Scott Gilliland along on a trip to an IAC meeting (he’s an excellent autopilot). I’ve done cross-country trips to northern Michigan and just short of the Mississippi and back.

And there’s one other use to which I’ve put the rating that’ll be the subject of an upcoming episode. A pretty special episode.

There was actually a point right after the instrument rating when I wondered whether I might run out of challenges in aviation. I only thought that because, even at something approaching 200 hours total time, I still didn’t really know much about the cooler nooks, crannies, twists, and turns that are out there and available for almost any pilot to investigate and discover. I’m a little smarter now. And I’ve only really scratched the surface.

Stay tuned.

************************************

Airspeed is trying something new! If you’re listening to Airspeed, the chances are pretty good that you’d enjoy listening to full-length audiobooks or similar content. Maybe you already do.

In any case, if you don’t already use Audible.com, you’re missing out. Audible has more than 100,000 audio programs from more than 1,800 content providers that include leading audiobook publishers, broadcasters, entertainers, magazine and newspaper publishers, and business information providers, all digitally downloadable and played back on any of more than 500 popular devices. If you’re listening to this podcast, you already have all the tools you need to listen to content from Audible.

You guys know me. I’m a partner at a large law firm, I produce this podcast, I fly a lot, I have an active family, and I’ve got two feature films in post. Busy? I invented busy.

But I still consume four or five books each month. The only way I can do that is to turn downtime into productive time. In the car, at lunch, while traveling, or any other time when I’m not writing, talking, or flying – I’m listening. I’m a platinum member and I get two books a month. And I occasionally end up buying more than that with the help from car loans for bad credit and other financial aids.

If you sign up for a free Audible trial right now at www.audibletrial.com/AIRSPEED, Audible will give you a free audiobook of your choice. And, when you do that, Audible will toss some money Airspeed’s way so that Airspeed can keep bringing you great aviation and aerospace content.

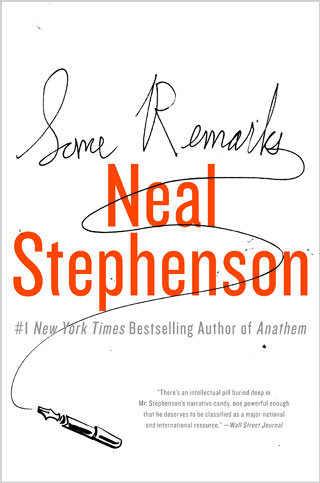

This time, I’m recommending Neal Stephenson’s Some Remarks. If you’ve read Cryptonimicon, The Baroque Cycle, Anathem, Snow Crash, or any other Stephenson work (except Interface, which sucks), you know Neal for his finely-crafted, cerebral, engaging stuff. Truly worthy of the Airspeed audience. In Some Remarks, you get unfiletered Stephenson in the real world, talking about everything from working at a treadmill desk (and I wrote this at a treadmill desk after hearing about it in this book) to touring the world to understand the longest undersea communications lines and understand why they matter to you.

Sign up for a free trial today and Neal Stephenson’s Some Remarks is yours free. And Audible will give Airspeed some money. Win-win!

Great Read, and congrats on the rating!

So when are you going to fly real gliders? Trust me its _a_ lot_ of fun.

If you are running out on challenges in flying, go and fly glider withoud engine cross county. Every flight is than a challenge.

Stephan

We fly without engine because we can

Good job, Steve. I just got my commercial, but the old fashioned way, in a 2-33. The oral was 3 hours long and more grueling than my rather perfunctory Ph.D. “final”, followed by 2 flights, but the people at Arizona Soaring prepared me very well–3 intensive days of flying followed by a long one-on-one review with the CFIG. The examiner, Terry Brandt, couldn’t have been calmer or fairer. On our first flight we finished the maneuvers early and since there was some altitude left I said, “I can’t believe I’m saying this, but is there anything else you’d like to do?” (He didn’t and we just enjoyed a nice flight past the peaks.) Good preparation doesn’t eliminate nervousness, but it sure makes it more manageable.