We’ve been keeping it under wraps for several months, but we just picked up Fafner from the shop at Cumberland Regional and we’re ready for the inaugural season of contests in the IAC’s Bob Hoover Class.

The Bob Hoover class is exclusively for GA aircraft certified under Part 23 with most aerobatic maneuvers prohibited by their AFM/POH. The class honors Bob Hoover, who was known for, among other things, flying aerobatics in airshows in a stock Shrike Commander. Hoovers fly the Primary Known (45 up, one turn spin, half Cuban, loop, acro turn, and slow roll), but are judged as a class separate from Primary.

Like Bob Hoover did for the Commander, we have to take Fafner off his Part 23 airworthiness certificate and put him on an Experimental/Exhibition certificate for the contests. The only actual mod that we made was an inverted fuel/oil system that’s permitted by the IAC rules. We don’t plan to spend much time inverted or without G on the airframe, but keeping the gas and the oil where the engine expects them to be is a good idea, especially if we have to fall out of a maneuver. I don’t mind unusual attitude recoveries, but I like to have the engine available once I’m back right-side-up. The inverted system is STC’ed so, when we want to put Fafner back on a standard certificate, it’s just an inspection. We’ll likely do that this fall after the contest season.

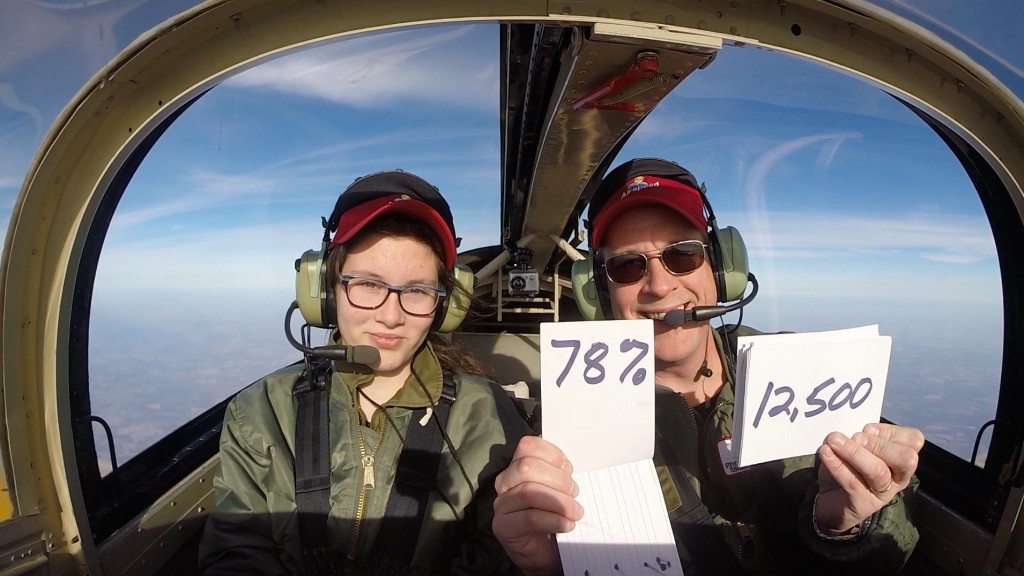

We’re going to have to get to the contests in short hops. With the STC’ed equipment, chutes, and our toothbrushes (and maybe just one toothbrush), we’ll only be able to carry 10 gal of gas. But that’ll be worth it. And the Tomahawk was made for this. It spins nicely and the entire weight and balance envelope is in the Utility category.

Other than that, we just need to get up in the practice area and get the maneuvers worked out. We’ll start up at 8,000 and then work it down to the 1,500 to 4,000 AGL acro box.

Watch for us at the Michigan Aerobatic Open at 3CM on 10 July, the Doug Yost Challenge at KSPW on 7 August, and the Yooper Looper at KSAW on 4 September. We’d fly more contests, but this is the inaugural year for the Hoover, there are very few competitors, and you have to have at least two competitors to fly for place. Based on several excited Zoom calls since January with other Hoovers, we’ll be going head to head with two Piper Archers and one C-172N. There’s no national championship contest for the Hoover Class yet, so no appearance in Salina, at least not as a competitor.