These are the show notes to an audio episode. You can listen to the show audio by clicking here: http://traffic.libsyn.com/airspeed/AirspeedCircusWithPreRoll.mp3. Better yet, subscribe to Airspeed through iTunes or your other favorite podcatcher. It’s all free!

There are three things you need to know about yourself. Who you are, what you want to be, and, if there’s a difference between the two, what you’re going to do about that difference every day for the rest of your life.

Sometimes, the act of answering those questions creates a change that alters who you are in profound ways. I answered those questions in 1998 after I watched the Tom-Hanks-produced HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon. Being honest, the answers were (1) law student and soon-to-be-lawyer, (2) astronaut, and (3) – well, what?

Shortly after passing the bar and beginning law practice, I decided to look into flight training. Even knowing that becoming an astronaut was a non-starter, being the pilot in command of an aircraft was a pretty good step in that direction and it gave me most of what I needed in the way of inspiration.

It wasn’t long after becoming a pilot and beginning to add additional ratings and endorsements that I began to regularly go to airshows. The desire to get close to airshows largely spawned the podcast to which you’re now listening, still active more than seven years and 200 episodes later.

I’ve been in the photo pit and on the ramp and actually inside the airshow box during shows for years. I remain thankful to Roger Bishop, Patti Mitchell, Brett Bailey, and others at airshows from Battle Creek to Indy and otherwise for truly wonderful access.

But the perspective that I had, and that I conveyed, was that of a fan. There’s nothing wrong with being a fan. But I wanted to go deeper. I wanted to know what it was like to be a part of the show. To get so close to the performers, the crews, the air boss, the announcer, and the others who actually put on a show that I could tell a real story from that perspective.

The International Council of Air Shows, or “ICAS,” is the professional association for the airshow industry. I don’t usually read mission statements directly here on the show, but ICAS’s is pretty concise and I’m not sure that I could paraphrase it any better. It is: “(1) To maintain safety, (2) to serve as an information resource on air show issues for those within and outside the industry, (3) to provide for the training and continuing education needs of ICAS members and air show professionals generally, and (4) to promote the air show industry to the media, corporate North America and the general public.”

I’ve attended the ICAS convention in Las Vegas for four years now. ICAS has granted me credentials each year and even listed me as a member in its semi-annual directory. (That’s gotta annoy Sean Tucker to have a poser like me so close to him alphabetically in the directory, but so be it!) I’m grateful for that. And it gives me a chance to do what I did next.

At the ICAS convention in Las Vegas the preceding December, I spent a lot of my time in the halls casting around for opportunities to actually embed with a team or otherwise get as much of a performer’s perspective as I could.

I connected with, among others, Mark Sorenson of Tiger Airshows. Mark agreed to let me be a crew dog at the TICO Valiant Air Command Air Show at Space Coast Regional Airport (KTIX) in Titusville, Florida the following March. In addition to my usual gig of setting up cameras and audio gear and covering the show as a media guy, I’d help to prep the aircraft, help out on the ramp, and – when the time came – head out to show center and help out with the pyro.

When March rolled around, I packed up my usual assortment of cameras, audio recorders, and other gear and hopped a commercial flight to Orlando, Florida. I grabbed the rental car and then headed for Melbourne to pick up Mark. Mark is a 717 captain for a major airline and he flew standby down from his home in Georgia to Melbourne. He had flown in the Valkaria airshow a week or two prior, so and he had arranged to keep his aircraft at the Valkaria airport, which is only 10 miles south of Melbourne and, in any case, a lot closer to Space Coast than his home in Georgia.

That meant that I’d have the chance to talk with Mark between the time I picked him up at Melbourne and when I dropped him off at Valkaria. I picked him up and then we hit Hwy 5 southbound. We stopped at The Shack, a restaurant in Malabar.

I’ve long thought that it’s hard to be in the business of being an airshow performer. Lots of guys go slowly broke (or quickly broke) in the airshow business. You see at least a few at every ICAS convention. A guy or gal with a brand-new portable booth. A highlight reel showing on a laptop. A hungry look in the eye. And no foot traffic. A look of quiet desperation that worsens as Day 2 and then Day 3 come and go. You usually don’t see them back the next year, at least not with a booth. You rarely see them perform at a show. I wanted to ask Mark about that and about what else one doesn’t see from the crowd line.

From the conversation with Mark and from what I gather from others, very few performers make it on appearance fees alone. Those who aren’t subsidizing their airshow habits with other activities usually have sponsors. Sean Tucker is powered by Oracle money. Mike Wiskus flies a red biplane with – proportionally – the largest logo in the airshow business flogging Lucas Oil. Mike Goulian has a deal with Goodyear (and, before that, Castrol and others). Red Baron Pizza used to sponsor a whole team. AeroShell, along with Honda and others, sponsor the AeroShell T-6 team. Heck, I got my DC-3 rating in an aircraft sponsored by Herpa, a miniature model company.

Sponsorships are hard to analyze. What does a sponsor get for the sponsorship? How much does the performer charge? What does the performer do? Sure there are lots of eyeballs and ears at an average airshow and in the media surrounding the show, but what’s the real value? Who are the sponsor’s customers? Will they be at the show? Will they be paying attention? Will they make purchase decisions that throw money into the top of the sponsor’s business machine in quantities sufficient to cause at least the amount spent on sponsorships to ooze out the bottom of the machine?

Is the goal immediate sales? Probably not the best option. Is the goal longer-term brand recognition? Much better bet. But it’s hard to tell. And it’s hard to give a potential sponsor a quantifiable business case during your sponsorship pitch when you don’t know yourself what the payoff is. I think you just have to hope that someone in senior management likes airplanes as much as you do.

Regardless of whether you have a sponsor, you need an edge. Something to differentiate yourself from the other performers. There are only so many high-performance monoplanes that an audience can bear to watch in a given day. Even me. It doesn’t matter how skilled the pilots are. If you put up rob Holland, Bill Stein, Mike Mancuso, Mike Goulian, Ben Freelove, Eric Tucker, and Kirby Chambliss in a row, you’re going to lose 95% of the audience after the second performer. Each of these guys is amazing. But, if more than maybe two of them are already booked to fly a show, you have a nearly zero chance of getting you and your high-performance monoplane booked to fly that show unless you’re part of a formation team with them.

Then there are slots for the Billy Werths and the Skip Stewarts and the Iron Eagles and the Red Eagles of the world who are flying biplanes.

And there are slots for the nostalgia or lower-power guys like Fang Maroney’s Super Chipmunk, Kent Pietch’s Interstate Cadet, John Mohr’s Stearman, or Greg Koontz’s Super Decathlon.

And then there’s comedy. Greg Koontz as Clem Cleaver, Mark Sorenson as Hotwire Harry, or Kyle Franklin or others doing one variation of another of the guy-steals-an-airplane routine.

There’s crossover, too. Greg and Kent land their aircraft on top of a camper, pickup, or other platform as well as flying acro. The Werth brothers incorporate a motorcycle into the demo as David Werth, riding a motorcycle, grabs the tail of Billy’s Pitts S-2C.

And then there are guys like Paul Stender who put jet engines in school buses and porta-potties. And guys like Rich Gibson, who create 1,000-foot-long walls of fire.

But the point is that airshow organizers have to come up with a good variety of well-paced acts to accommodate a broad audience and you, as a performer, have to be one of those moving pieces that fits properly.

There’s another odd thing that I can’t remember whether Mark told me or I heard it somewhere else. It’s the 300-mile effect. You have a much lower chance of getting booked by airshows that are within 300 nm of your home base. And, if you do, you tend to have to take less money or otherwise end up with less attractive terms. There might be an exception for your home town show. But I’m told that the 300-mile effect is real.

It apparently has to do with a prophet being in his own country. If you don’t live at least 300 nm away, you’re not exotic enough for the closer shows. Strange, but I have heard, at least anecdotally, that it’s true. And, incidentally, a real problem for a guy like me who’s affiliated with a team that flies motorgliders whose operational radius for airshows is, realistically, about 250 nm.

Mark and I talked a lot about various ways to be a niche player while still having a broad enough appeal to capture and hold audience attention and get invited back.

Mark flies a Yakovlev Yak 55. It’s a cantilevered monoplane that’s about 24 feet long, nine feet tall at the tail, and 27 feet wide. Most have a Vedeneyev M14P 9-cylinder radial engine that puts out 360 hp. And the prop rotates counterclockwise as seen from the cockpit, so anyone accustomed to using right rudder is in for a surprise the first time they fly the Yak 55. It has a single-place cockpit, a huge prop that requires very tall main gear, and a muscular stance on the ramp.

Mark’s act includes two flights on any given show day. The first is a solo aerobatic demo that culminates in some skywriting. Mark’s skywriting is a little different from what you’re used to because he does it vertically, standing the letters up over the runway several hundred feet tall. He does an I-heart-U at the conclusion of the initial demo.

The way he does the heart is pretty cool. Instead of putting two Cubans back to back, he does it all in one loop that’s pinched at the bottom and has a snap roll at the top. Essentially an avalanche with a pinched entry and exit.

The second flight occurs later in the show and involves the ground crew a lot more. Where the first demo is called “Tiger Airshows,’ the second adds the “Ringmaster.”

Mark noticed the same thing that you’ve probably noticed if you’ve been to an airshow that features pyro. If the winds are light or calm and the explosion happens just right, a huge smoke ring rises up from the detonation site. It’s called a toroidal vortex. The smoke simply shows an area of air that’s rapidly rotating in a donut shape.

Mark wondered whether he could fly an airplane through one and whether the audience might like that. Eventually, he did. And the audience did. Great! But smoke rings like that are relatively rare in pyro displays. After all, pyro displays aren’t usually trying to create smoke rings. They’re simulating the effect on the ground of strafing runs by the aircraft overhead. And, even when a smoke ring goes up, there’s usually a demo going on above it and a Yak 55 would be unwelcome at show center, to say the least.

So Mark and his friend James Hammons went about coming up with a way of creating great big smoke rings reliably and without having to have somebody like Rich and Dee Gibson on site to manage it all. They succeeded.

The pyro setup consists of three barrels placed in a line 50 feet apart. Each barrel has a pole sticking up vertically and there’s a horizontal ring at the top of the pole. The ring is attached to an LP gas cylinder and it provides the pilot light for the main smoke generation burn. The trade-secret stuff is in the barrels themselves. I have seen the stuff in the barrels, and I am duty-bound to say no more about the stuff other than that it operates by FM.

Suffice it to say that, at the activation of a switch on the control console, a high-pressure columns of flammable stuff fires up through the flaming ring, thus creating a jet of flame that very shortly makes a roiling black toroid of smoke. There is a simple but precise process for recharging each barrel and James accomplishes this by the operation of a number of switches.

If the wind is reasonably calm, the rings thrown up by the barrels will ascend at between 100 and 500 feet per minute. Mark then flies through the rings in a number of entertaining attitudes. If the wind is high, the rings usually don’t form or they dissipate quickly. But there are still blasts of fire and black smoke and those are cool regardless of whether they form rings.

The pyro is usually set up at show center (and, sometimes, the orange Ringmaster trailer is the show center marker). Mark flies acro back and forth and makes passes at rings as they present themselves. With three barrels throwing up rings or near-rings every 20 or 30 seconds, there’s usually a good target and it’s not hard to think that it’s all planned precisely.

Mark also had a second Yak 55 in the paint shop at the time and was on the verge of expanding the show routine to include two tiger-painted aircraft.

*****

We finished lunch and continued on to Valkaria. Mark’s Yak was in the main hangar next to the Brevard County fire station and mosquito control operation. Mark had to take care of some business, so I took the opportunity to climb all over the aircraft and identify camera mount points. I placed three in the cockpit just to see how the angles would work. Mark came and preflighted, then we pushed her out of the hangar. Mark started it up taxied out, back taxiing on Runway 32, then roaring past the hangar on his way north to Titusville.

I drove up to Titusville and connected with Mark at the Valiant Air Command museum there on the airport grounds. Mark had, of course, beaten me there handily, but he had also flown his skywriting sequence at altitude on the way so he could say with a straight face when he signed the waiver that he had practiced his routine recently. I retrieved the cameras and audio recorder and helped to wipe down the aircraft and put it in the hangar.

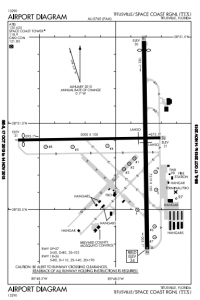

By that time, James Hammons had arrived with the Ringmasters trailer. We grabbed radios and headed out onto the field to set up the pyro. If you’re following along at home, show center was just north of the midpoint of Runway 9/27. There’s a taxiway – Taxiway B – just south of that and parallel to it. The crowd line is a little further south of that and also parallel to the runway.

Prior to the flying part of the airshow, many of the aircraft, including Mark’s Yak, are set up on a wide ramp area just off to the crowd’s left so the crowd can see the aircraft up close and personal. You can get directly from that ramp to Taxiway B and turn left to get to the threshold of Runway 9 or turn right to get to show center or the threshold of Runway 27. If you’re going to show center, you cut northwest on Taxiway C and then to the runway.

We pulled the trailer onto the ramp, made that right turn, and then cut north, across the runway, and to a point maybe 100 feet north of the runway. We deployed the three barrels and their associated control systems. James got out the control panel and set up the control station next to the trailer. We tested everything short of actually setting things on fire.

I kept quiet and just reached in and grabbed stuff that looked like it needed carrying. Otherwise, I tried to pay attention to the moment. If you didn’t look around you – or if you squinted when you did – it would be very easy to miss that we were in the middle of an airport. Other than the fact that the grass has been mown pretty short, this could be any open field just about anywhere.

I looked over at the crowd line, maybe 800 feet south. I could see the fence and several of the static display aircraft. The tents and booths were already set up. It was only missing a crowd. It feels pretty isolated out there at show center. It’s quiet. It’s a long way from the crowd line. I’m here amid the machinery of the airshow. But it seems separated from the elements of an airshow as I’ve experienced them up until now. I wonder if it’ll be different when there’s a crowd over there and all manner of aircraft screaming up and down the strip of pavement right over there.

Once we were done setting up, we headed back to the ramp. Everything was basically in place and ready for the morning. The crew made plans to arrive early the next morning for the brief and I climbed back into my rental car and headed back to the hotel. I had video and stills to offload and a blog post or two to put up. And, truth be told, I still had a distribution agreement to draft and send to one of my clients. Switching modes on the drive back from the airport to the hotel was jarring and discontinuous, as it always is. Going from getting up-close access and setting up pyrotechnics in a field near the Kennedy Space Center to writing an agreement for co-development of a fuel management system.

I stayed up way too late because I spent too much time on the video and stills from the day and then had to stay up even later to get the agreement done and e-mailed to my client.

It was ever thus . . .

*****

The next morning, I was up at the crack of dawn and off to Mark’s hotel to meet up with the team. I had the non-trivial task of getting my rental car onto a hot ramp next to Mark’s aircraft. We didn’t have a car pass for me yet. I was going to tailgate Mark and James in the pickup and hope that a “he’s with us” at each of the respective checkpoints got me through. Thus, meeting up with the merry band of performers and regular crew was critical.

Over breakfast, I got to talk to Mark’s wife, Brooke, for the first time. And I got to talk to James some more. It became obvious that these people have known each other for a long time and were friends long before the airshow act came into being. In addition to being a pilot, James is a musician. He promised to play some of his music for me later. And I got the story of how he and every other member of his band can’t stand playing Margaritaville. It’s the same for Dixieland jazz bands and When the Saints Go Marching In. His band once passed around beer pitchers and took up a collection to pay the band not to play Margaritaville – and ended up collecting an amount that almost exceeded the pay for the gig in the first place.

Soon enough, breakfast was over. The caravan rolled out of the restaurant parking lot and out onto Columbia Boulevard for the short drive to the airport.

It was Friday. At most shows, Friday is a practice day. It allows performers the opportunity to get used to the show site, the air boss, and the other performers. Most FAA waivers require that each performer have practiced his or her demo with in the last 15 calendar days. And it’s no joke. There’s a blank for your last practice date on the waiver where you fill in your information and sign. Friday is a chance to get that practice in. The weather and other factors don’t always cooperate, so it’s not a bad idea to practice other than on the Friday of a show weekend, much like Mark did the day before on the way from Valkaria.

Friday practice days are usually less stressful. The acts might not fly in the same order in which they expect to fly the shows on Saturday or Sunday. If an act is late making it to the hold-short line, it’s not a crisis. But the air boss and the performers otherwise usually fly the Friday practice as closely as possible to the way they expect to fly the Saturday and Sunday demos. Some ancillary performers, like the singer for the national anthem, don’t show up on Friday. If you’ve been to a Friday practice where Rob Reider is the announcer, Rob will actually sing the anthem himself.

So it’s not a full-up airshow day. But that doesn’t mean that the gas or smoke oil or police or other expenses that organizers pay are any less on a Friday. Organizers have figured this out and it’s pretty common that Friday gets called a “media day” or “sponsor appreciation day” or something similar. And, most importantly, the grounds can be very nearly as full as they are for Saturday or Sunday. Even if those folks aren’t paying admission, they’re paying for parking and they’re buying walking tacos and lemonade and Blue Angels keychains. I know of at least one charity show that has covered all of its fixed expenses solely with the revenues that it received on the Friday practice day.

The caravan weaved its way toward the airport. We passed volunteers stringing miles of twine between stakes to keep cars from parking along the side of Columbia Boulevard. A double helping of twine and stakes marked the zone off the approach end of Runway 18. Beyond the entrance, the place was already hopping with volunteers, police, EMS, performers, media, and others.

The Valiant Air Command Museum is on the east side of the field, diagonally from the crowd line. We stopped to let Mark out so that he could taxi the Yak over to the ramp. And, somewhere in the process, I got disconnected from the caravan.

Access at airshows varies widely and there’s no good way to predict whether you’ll have a hard time getting where you need to go. Especially when you need to get to a part of the field like the performer’s ramp. I’ve actually had trouble at times even though I had the right hang tag on the rear-view mirror and the right wrist-band on my wrist. Other times, I’ve smiled and nodded and behaved as though I’m supposed to be there and been waved through with a smile.

I was lucky this time. The first fork in the road was guarded by a Civil Air Patrol cadet. I read his collar insignia and addressed him as the cadet senior airman that he was. This immediately took down his guard. No adult can read cadet insignia unless the adult knows what he’s doing and is supposed to be there. Heck, most adult CAP members can’t read cadet insignia. I explained that I was going to the performer ramp and I point to my camera bag and pile of towels. By whatever calculus that went on in the young man’s head, I must have seemed like an acceptable risk and he waved me through. I noticed in my rear-view that the cadet did not let the next guy through and I saw that guy backing up to join the other line of cars that was being shunted to spectator parking.

A couple of other barriers. At one point, a police officer held me up and then escorted me down the line on the ramp. But I ultimately found myself parked behind the Yak. I grabbed such cameras and other gear as I thought I’d need and headed with Mark and James to the briefing.

By the time the briefing ended, the gates had opened and the public was beginning to wander the ramp in earnest. There was maybe two hours between the end of the briefing and the beginning of the show. During that time, the performer ramp is open to the public and the foot traffic picks up all morning until the ramp closes for the show.

I spent a lot of time just hanging around the Yak. The sky was generally gray and there were rain showers every half hour or so. After the rain passed, I occupied my time wiping down the Yak. I imagined that this motivation is similar to that of people who have recently quit smoking or who are attending a nudist camp for the first time. It’s something for your hands to do.

I wore an orange polo shirt and cargo shorts, so I looked like I belonged with the aircraft. And, in fact, people asked me when I was going to fly it. I explained that I’m just ramp crew today and that they could see me in a few hours out on the field blowing stuff up. They were less impressed by that. So I added that I’m a Sierra Hotel search and rescue pilot. They were still less impressed, but I felt a little better.

When the time came, I set cameras on the Yak and Mark went out and did the initial skywriting act. Not a lot for the ground crew to do but recover the aircraft when Mark came back in.

But then, two or three acts before Mark flew the Ringmaster routine, I got into the truck with James and we headed out to the trailer at show center to get ready.

My job was to stand near the middle of the barrel array with a heavy pressurized-water fire extinguisher and put out the airport whenever the airport caught fire. Which, it turns out, is pretty often. Anyone who doesn’t live in Florida thinks of Florida as a low-lying, soggy place. And it is soggy a lot of the time. But not in March. In March, any rainfall leaches down into the sandy soil pretty quickly and the surface gets pretty dry. And flammable.

I’d stand there shooting with my still camera. After every pass, I’d look at each of the barrels and James would keep an eye out as well. About once every five or so discharges, some stray spray would make it onto the grass within maybe 10 feet of a barrel. When that happened, I was supposed to run over to the area and hose it down. Then I’d shoot again until another fire started.

As the Ringmasters act began, James pressurized the system and assumed his position at the control board. I stood a respectful distance away from the middle barrel with a fire extinguisher at the ready and a still camera in my hand.

Mark came charging down the runway, built up a head of steam and then pulled up. James fired off the first barrel as Mark went by, sending a up a pretty decent ring of smoke. Mark executed a hammerhead and headed back toward show center, aiming for the ring.

The act was a blur of activity. James fired off barrel after barrel, orchestrating which ones were charging, which ones were ready, which one was firing, and which one was surrounded by a grass fire and a guy with a heavy fire extinguisher running toward it.

All the while, Mark worked his way back and forth across show center. At each turnaround, he’d look down for a smoke ring. If he didn’t find one, or if he wanted to give one a little time to rise and expand, he’d do something entertaining to make time – usually a pass back to the other side or a quick swing back away from the crowd before coming back. When he saw a ring he liked, he’d come in toward show center to play with it. Most of the time, he approached the rings from below and pulled up through them. Sometimes, though, he’d get creative and cut through on knife edge.

The wind on Friday was brisk and it was toward the crowd. That meant that the smoke rings didn’t form as easily because the wind disturbed the establishment of the toroid. And we were set up maybe 100 feet away from the line of closest approach to the crowd, so the on-crowd wind sometimes took the smoke rings too close to the crowd to permit Mark to chase them.

We had a few grass fires, but none ever got anywhere near out of control. Each of them was made up almost entirely of the flammable stuff from the barrel and it went out as soon as that material was consumed. But I hosed it down anyway just to be sure.

I had set up GoPro Hero cameras on the ground near one or more of the barrels for each session so that I could capture footage for a possible video episode. On one occasion, I ran up to find that a quantity of flaming stuff had landed on or near one of the cameras and it was cooking the camera. I’m glad that my cameras can’t talk. I clamp them to aircraft. Sometimes on the outside of aircraft. I put them where fire can rain down on them. I’m downright abusive of my cameras. I hope they never unionize. They should, you know. They totally should.

*****

Saturday was much the same as Friday, with the exception of fewer clouds, no rain, more wind, lower-quality smoke rings, and a hang-tag for my rental car.

We fell pretty quickly into a comfortable routine. Briefing, pre-show prep, launch and recover the teaser, do the pyro, and then prep for the next day.

As long as things exploded or burned at the appropriate times and we weren’t out there when it was manifestly unnecessary for us to be out there, we had a lot of flexibility to hang out at show center before and after Mark flew. To my mind, that was the best part.

James played some of his band’s music on the truck’s stereo as we drove out and back or sat in the truck awaiting the start time. At one point, turning off the runway and into the grass by the trailer, I got to yell “Runway light! Runway light!” I’m pleased to tell you that the brakes on the truck functioned well and that no runway lights were harmed in the making of this episode.

We saw a series of T-6s, the WWI Snoopy and the Red Baron aircraft, a relatively new airshow pilot flying a Laser 200 reminiscent of Leo Loudenslager’s act, an L-39 racing a jet car, and several overhead passes by a B-2 Spirit. All directly overhead. In fact, when the B-2 came over, the boss called out the our trailer as the flyover point. We thought about running. But, having discussed the prospect of merely dying tired, we stayed and shot pictures.

I really enjoyed being a grunt and having the camaraderie of the airshow family. But the biggest take-away was the experience at show center.

Very few people get to see an airshow from show center. In fact, I can’t think of anyone other than the pyro crew who regularly spends the show out near show center.

It’s not like being backstage. It’s not like watching a show from the wings. It’s not like being on the announcer’s stand or even right on the crowd line. If I had any expectation, it was probably a general sense that it would be noisy and exciting. In fact, it’s mostly quiet.

It’s a lonely place. The crowd is at least 500 feet away if you’re on the Cat III line and, if there are jets in the show and there’s a Cat I line, you can be 1,500 feet or further away. You can’t hear the announcer or the music. If you weren’t looking within the maybe 90 degrees of your field of view that the crowd occupies, you might not even know that an airshow was on. It’s kind of surreal. Even with a performer tearing it up in the box, it’s mostly pretty quiet. Aircraft are nearly silent as they approach you. There’s noise as they pass abeam you. But that noise usually lasts less than a second or two and the performer passes you and the noise recedes into the distance.

I know that many airshow photographers lust after positions closer and closer to the action. But I can tell you that there’s a point at which closer is not better. At show center, all you shoot are noses, underbellies, and tails.

This is where the business of the airshow happens. This is the picture that performers see. It’s a lonely stretch of flat ground. The crowd area looks small compared to the surrounding area. The only sense of activity other than your own comes from the constant radio chatter of the air boss and the other performers launching, recovering, and moving around. And if your team uses a discreet frequency for its demo, you don’t even get that. You just have the team.

I know that you and I have certain emotional reactions there on the crowd line watching the performers and listening to the music and the narration. The best performances cause all of those elements to meet and mix there at the crowd line and create a big impression on the crowd. An impression big enough to make a guy like me project myself up into the box and wonder hard enough about what that’s like to cause me to be here in the middle of a field a thousand miles away from home, holding a fire extinguisher and having thoughts like this.

Out at show center on the Cat I line, it’s quiet and it’s lonely. If you’re going to fly in this place, you have to fly your demo as well as you can and trust that what you’re doing is making the impression that you want to make. Because, when all is said and done, Danger Zone doesn’t play for you and there’s no cheering or fist-pumping as it’s happening. It’s like it always is inside your headset or your helmet. You’re alone with your eyeballs, hands, and feet and aerodynamic forces and energy management.

I am disappointed by this. But, at the same time, I am thrilled. Ira Glass says that the story doesn’t really begin until things go completely sideways from what you expected and you have to leave your preconceptions behind. Saturday afternoon, I walked back to the truck, leaving a pile of preconceptions in a little heap just north of the midpoint of Runway 18/36 at Space Coast Regional Airport. They’re still there if you go look for them. Right near one of several circles of charred grass.

[...] Online, Three part series: Inside Airshows. Part 1: Running Away to Join the Circus, Part 2: With a Mic in My Hand, Part 3: Tuskegee [...]