Late last week, I saw a post on WIRED’s website by Adam Rogers called Space Tourism Isn’t Worth Dying For. In 12 insipid paragraphs, Mr. Rogers delivered a tortured hash that boils down to: “Don’t hate me bro. I loved Apollo and the shuttle program, but now it’s all about dilettantes with money going up for thrills.”

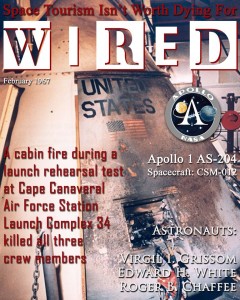

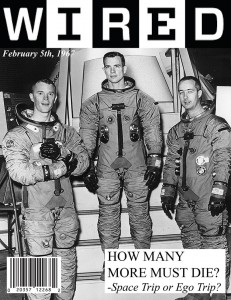

Shortly thereafter, I suggested on Facebook that, if somebody would mock up a WIRED cover or logo, I’d write a parody to the effect of WIRED Responds to the Apollo 1 Fire. Two talented friends mocked up covers and posted them in comments. Bryan Rivera of Windtee Aviation Art was first to post and his cover leads this post. Thomas Freundl also posted an excellent cover that’s featured below.

But, much as I tried to make good on my promise, I had reservations about the Apollo 1 parody. It’s not that I couldn’t do it. I know my NASA history as well as any aerospace geek and could come up with an almost exactly parallel parody article. But I realized that to do so would be to talk past Rogers when what’s needed is a direct response. So here it is.

Rogers claims to be a fan of space exploration. He says that he likes spaceships. He’s been to the Cape and to Mojave. And this and other hedging qualifies him to “call bullshit” if anyone speaks of the SpaceShipOne accident in terms of giant leaps and boldly going where no one has gone before.

I write to call bullshit on Rogers.

Rogers says, “Do human beings have a drive to push past horizons, over mountains, into the unknown? Manifestly. But we always balance that drive and desire with its potential outcomes. We go when there’s something there.” In this insipid word salad, Rogers proves that he has no idea what drives those who dream about space travel.

There’s something there, alright: It’s the there, stupid.

Even if it’s a suborbital trajectory, it’s space. It’s the chance to see the curvature of the planet that has been the origin of every human song, play, book, thought, hope, and dream. It’s the chance to be up there and experience the Overview Effect attested to by Ed Mitchell, Chris Hadfield, and Mike Massimino, among others. In fact, I’d be willing to chip in to fund a sub-orbital (or better) flight for every incoming leader of a nuclear-capable county if we could make it mandatory before taking the oath of office.

Not every Virgin Galactic slot-holder is an explorer. To be sure, some almost certainly have more money than brains and are just in line for the thrill. But I’d venture to guess that the vast majority of slot-holders are those genuinely moved by the prospect of being in space, even for a few moments.

Additionally, a functioning regular sub-orbital service is a valuable step in preserving and building space capability. NASA, for all practical purposes, finished up its manned suborbital program with only two such flights in 1961. After that, it was all about orbit and beyond though the remaining four Mercury flights and all of Gemini, and Apollo. You have to be good at different things to regularly fly people in sub-orbital profiles. Virgin and others are filling in some of the blanks that have been there for 50 years. And they’re building physical and intellectual infrastructure that will further commercial spaceflight beyond sub-orbital levels in the near future.

Rogers simply doesn’t understand that aviation and aerospace technology is rarely single-purpose or merely horizontally integrated. We’ll learn things doing sub-orbital flights that apply to every aspect of space flight. In fact, some elements of commercial sub-orbital flights are more likely than other kinds spaceflight to help develop some elements of vital aerospace technology and practice. Look at the higher operational tempo. Look at the requirements for efficiency and reusability in launch and recovery. Look at the crew training, preparation, and performance elements. These and other operational considerations will force innovation that we wouldn’t otherwise see. For Pete’s sake, the very existence of White Knight/SpaceShipOne and White Knight Two/SpaceShipTwo in the first place is demonstration enough.

Is Rogers’ problem with the private-sector nature of Virgin Galactic’s operations? Look, it’s pretty obvious that there’s little present public support for government-backed manned space exploration, at least in the US. Commercial spaceflight is our best bet for preserving our space exploration chops and moving them forward. It’s also a place where the know-how of space veterans is preserved and where it’s passed on to the next generation. Like it or not, this an essential funding model for the next step in space exploration.

Is Rogers’ problem the lucre that it takes to get humans into space? Surely it’s not the money itself. The Apollo program cost $100 billion over 10 years and of the Space Transportation System (the “space shuttle”) cost $200 billion over 40 years and that’s apparently okay with Rogers. Must money be spent by a government in order to make it noble or worth risking life over? How is it less noble when the money comes from those who have it and are moved to invest it? Might private money be even more noble?

Private space operations are the way of the world for the next Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo. It’s not what I expected growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, but it’s what we have and, in many ways, it’s even more exciting. I’d be just as happy to go into space with Delos D. Harriman or Richard Branson as with Neil Armstrong or Dave Scott. To be sure, it is no less noble and perhaps it is even more so. The motivation remains as pure as it ever has been at any other time or place. We have not stopped dreaming. We’re going back to space. Sub-orbital now. Low-Earth orbit next. Then outward. Ever outward.

But Rogers goes even further. He says right up front that test pilots take risks and die “in the service of millionaire boondoggle thrill rides.” He most likely says this because he has zero idea about what motivates these people.

There’s a very special breed of men and women who live for aviation and aerospace and sharing that love with others. While test pilots are such men and women, I don’t know any test pilots. But I do know airshow performers, and they’re cut from the same cloth. These people don’t do it for the fame. The average American can’t name a single Thunderbird or Blue Angel, much less come up with the names of Greg Koontz, Mike Goulian, Patty Wagstaff, or Rob Holland. Airshow performers generally don’t do it for the money. It is said that one can make a small fortune in the airshow business – if one starts with a large fortune. These are words that are more true than any airshow performer likes to admit.

They do it because they love to fly. They love to operate in the less-occupied reaches of the envelope with engineering, skill, and determination. They love to fly at airshows and they know that some of the kids who see them fly will walk off the field each weekend with new purpose to their lives.

I don’t speak idly here. I’ve done it myself. Not often or particularly thrillingly, but I’ve stuck my head into that rarefied box air in front of 20,000 people on several occasions. I’ll breathe that air again any time they let me and I’ll spend the hundreds of hours in training and preparation to be worthy of that trust and honor.

Almost every year, one or more of those people die in the pursuit of that love. It’s never easy when that happens. We all know exactly what risks are involved. We prepare as best we can for the risks and then we execute with clear purpose and a safety culture that is second to none. Have you ever tried to live up to a standard like that? Perfection is expected, but mere excellence is tolerated. We feel awful when one of our fellows dies or is injured. But we understand the drive and we all believe that what we do is worth the risks that we assume with open eyes.

Pilots – or at least the pilots that I know and model – don’t operate in the service of millionaire boondoggle anything. They serve the highest aspirations of our species.

Rogers is wrong on every count. He doesn’t understand why we dream about space. He thinks that government is the only proper mechanism to fund space travel. He doesn’t understand how technology is preserved and enhanced. And he sure as heck doesn’t understand pilots.

So, finally, I speak for thousands, if not millions, of my fellow dreamers when I say this: I’ll gladly train up, suit up, and strap into the very next available space vehicle. And, if it helps, I’m a commercial pilot with about 600 hours in my logbook; a little bit of it in jets and a lot of it in gliders. My resume and logbook are available to anyone at Scaled Composites, Virgin Galactic, Orbital Sciences, or any others who are interested. For that matter, SpaceX already has my resume.

In any case, so say all of us: Bullshit, Mr. Rogers.

Bravo Zulu!