Time has been amazingly scarce these past few months. But that doesn’t mean that I can let the rust build up on my wings.

Last weekend, I got up with Team Tuskegee for some three-ship formation deep in the Detroit Class B. I needed some echelon takeoff and landing experience, so I flew 2 in a phantom 4 configuration, landing and taking off abreast of lead on 21L at Detroit Metro (KDTW). John Harte ably flew Lead and Chris Felton flew a very competent 3 (or, as he likes to be called, “Element Lead”). We also got in some tail chasing and other more general formation work with me flying 3 and Chris as 2.

I took along Alex Craig, one of CAP’s check airmen in the Michigan Wing, with whom I’ve flown several checkrides over the years. Alex is an ATP with thousands of hours logged, but little time in gliders or in formation. Alex sat left seat to observe the formation work. And, as Tim Brutsche likes to say, flying an aircraft with an empty hole is a sin. Aviation is always best when it’s shared.

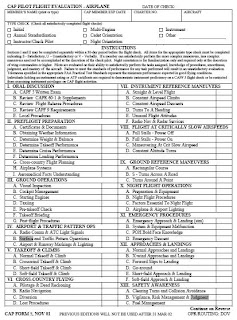

Then, this past weekend, Alex and I switched seats and aircraft and I flew a CAP annual Form 5 stan/eval ride. I hadn’t flown the CAP glass C-182T in maybe six months. Needless to say, I spent a fair amount of Saturday preparing for the Sunday-morning ride.

I approached this ride with more trepidation than usual, largely on account of the rust build-up. But I suppose that I needn’t have worried. I goofed up the throttle work a little (one of the few cross-contamination problems that I experience between the TG-7A and the C-182T) and I managed to forget which way the glideslope indicator was supposed to move and I got fairly high on the glideslope on the ILS 27 at KFNT.

But, generally speaking, the ride went far better than I expected. I’ve always hated landing the C-182T. I still do. It’s so nose-heavy. You run out of elevator pretty quickly in that aircraft if you’re CG-forward, as you almost always are when you’re flying with two guys and 60 gal. of fuel. The usual way to deal with that, namely keeping a little power in on the flare and flying it all the way to the runway like an airliner, isn’t an option for practice engine-out work. So it was all attitude and airspeed on many of the landings.

I did use one technique that I recommend to anyone who has hot hands with a C-172 but has problems with the C-182. Put 50 lbs of something in Cargo Area B. It moves the CG back a little and makes the landing flare a lot more controllable.

We rocked out the high airwork, did most of the landings (engine-out, soft-field, etc.) at Lapeer (D95), shot the ILS 27 and the RNAV 36 (twice) at KFNT, then flew back to Pontiac (KPTK), where I think I did my best short-field landing ever in that aircraft, getting it down and stoppable before the 1,000-foot markers.

Work and other commitments are still keeping me out of the cockpit more than I’d like to be, but I think I’ve done as good a job of getting active and proficient early in the season this year as I ever have.