These are the show notes to an audio episode. You can listen to the show audio by clicking here: http://traffic.libsyn.com/airspeed/AirspeedOAwith_PreRoll.mp3. Better yet, subscribe to Airspeed through iTunes or your other favorite podcatcher. It’s all free!

Earlier this year, I sat down with Rod Rakic, one of two co-founders of OpenAirplane, a service that allows pilots to complete a single Universal Pilot Checkout and then fly aircraft in which they’ve qualified at FBOs all around the country without the need for a local checkout. This episode contains that inverview.

I also did an OpenAirplane checkout at Crosswinds Aviation at Livingston County Airport (KOZW) in Howell, Michigan before having the conversation with Rod. I recorded audio on the flight, but couldn’t locate that audio to incorporate it into the episode. Thus, I wrote up a summary and included it in the episode. That summary appears below.

____________________________________

Okay, I looked for the in-flight audio for months. It’s going to turn up at some point, but there’s no use holding up this episode any further in the hopes that I’ll find it. So I’m just going to give you an account of what happened. Besides, doing this will cause the file with the in-flight audio to magically appear in a directory somewhere and I’m curious about where it is.

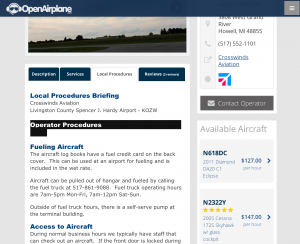

I showed up at Crosswinds Aviation at Livingston County Airport (KOZW) early on a Sunday morning this March. I had already read the local briefing from the OpenAirplane website. Despite the fact that I’ve been to this airport a couple dozen times and had even flown by commercial checkride there, the local briefing told me a few things that I didn’t know, including Crosswinds’ specific information about fueling and obtaining oil.

Shortly after I arrived, I met Scott McDonald, who would be my check pilot for the ride. Scott is a CFI and CFII who’s been flying professionally for five years and instructing for about half of that. He started out flying in Alma, Michigan and did his CFI training at Lansing Community College.

We began the checkout as all OpenAirplane checkouts begin – By reviewing pilot documents. Airman certificate, medical, logbook, and the other usual stuff. Then we covered the kind of ground review that you’d expect when checking out to fly at an FBO or getting a flight review. Here’s some of the audio of that phase.

[Audio]

I had already begun the early part of my studying for my own CFI checkride, so I had no problem with any of the aircraft systems, regs, or other information that Scott covered. Lest you be intimidated, he didn’t ask me anything that a pilot of a single-engine airplane shouldn’t already know as a matter of course.

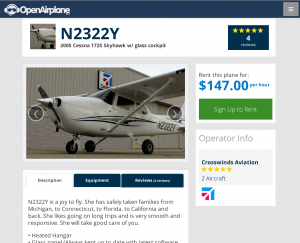

After that, we headed out to the hangar to meet our steed for the flight. N2322Y is a 2005 Cessna 172S with a G1000 glass cockpit. The preflight inspection checked out fine after I added a quart of oil. Fuel was about half full – plenty for the time that we were going to spend aloft.

I have maybe 70 hours behind the G1000 in C-182s and one jet and maybe 200 hours in C-172s, but no time in a C-172 with a G1000 panel. At the end of the day, neither Newton nor Bernoulli care about the panel, other than maybe the fact that the aircraft is a little heavier in the nose with all of the avionics. I briefed with Scott that this was my first time in a glass C-172 and we tried to figure out what could be different. We couldn’t come up with anything, but Scott allowed as how he wouldn’t climb into the back for a nap and I allowed as how I’d tell him if I had any difficulty.

We started up, taxied out, and took off about 15 minutes later. I used all of the available checklists and called out everything I was doing verbally so that Scott always knew what was on my mind.

It had been severe clear a few hours earlier, but cumulus clouds had started to build. A cool atmosphere with uneven heating of the surface by the sun resulted in what would turn out to be a great day for early-season soaring by glider pilots. It quickly became apparent that we were going to have to get on top of the scattered layer to get the airwork done, so I picked a hole and back-to-back chandelles got us above the layer and into some smoother air. Once established, I did clearing turns and demonstrated steep turns, slow flight, and stalls.

Satisfied with my VFR airwork, Scott had me put on the hood and we began the IFR part of the checkout. You can check out VFR-only if you want to. But I wanted the IFR privileges and also needed to get up and knock some of the rust off of my IFR skills. Scott put me through a couple of unusual-attitude recoveries, then called up Flint Approach to go in for some approaches.

We picked up a clearance and Flint gave us a descent for vectoring. That put us in and out of the clouds for the majority of the rest of the ride.

We shot an ILS and a VOR approach at Flint all the way to landing, using normal technique on the first one and short-field technique on the second one, and then accepted vectors back to Livingston for the RNAV 31. I hand-flew all of the approaches and the en-route parts. It was pretty bumpy in places, but my IFR scan came back very quickly and I think that I gave a pretty good account of myself.

Five miles out of Livingston County, we were in VMC, so we cancelled our IFR clearance and continued VFR. Scott had me stay under the hood to pattern altitude, then had me enter a left downwind for Runway 13, which the wind was favoring. Downwind abeam, he pulled the power. I pulled for 65 KIAS out of reflex, then called out the engine-out and restart procedures as I rounded the corner to land dead-stick.

The landing was uneventful unless you count some floating in the gusts once we got into ground effect.

We put the airplane away and headed back inside to debrief.

[Debrief audio.]

I was pretty pleased with the flight. A fair amount of rust on my skills and several imprecise things happened but nothing dangerous happened or even came close to happening. And now I’m checked out to go fly this or any other similar C-172 in the OpenAirplane fleet. A fleet that now includes 255 aircraft located at 73 operators on 71 airports in 32 states.

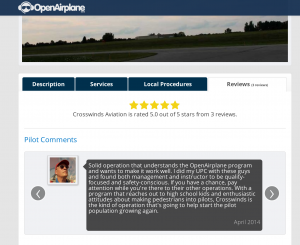

OpenAirplane allows both pilots and operators to leave feedback about their experiences. It’s a process that keeps everyone honest. My feedback covered my flight ands some of the things I learned about Crosswinds Aviation and it was as follows.

“Solid operation that understands the OpenAirplane program and wants to make it work well. I did my UPC with these guys and found both management and instructor to be quality-focused and safety-conscious. If you have a chance, pay attention while you’re there to their other operations. With a program that reaches out to high school kids and enthusiastic attitudes about making pedestrians into pilots, Crosswinds is the kind of operation that’s going to help start the pilot population growing again.”

____________________________________

Check out this episode’s Audible.com selection, Lock In by John Scalzi!