These are the show notes to an audio episode. You can listen to the show audio by clicking here: http://traffic.libsyn.com/airspeed/AirspeedTuskegee3WithPreRoll3.mp3. Better yet, subscribe to Airspeed through iTunes or your other favorite podcatcher. It’s all free!

If you want to understand a subculture or an experience, a great way to do that is to take an outsider and plunge him into the place you want to know about, wait awhile, then drag him back to the surface and wring him out to see how it changed him. It’s even better if you can get the guy to wring himself out. You begin to realize that not everybody who writes about the majesty of flight does it because he’s a fighter pilot. Some of us write because we’re not fighter pilots.

You also need to talk about the world in its own terms, using the lexicon of the world, sometimes without explaining the vocabulary to the uninitiated, except maybe through context. If you’re a pilot, you’ll understand most of this. If you’re not a pilot, that’s okay, because you’ll feel a little of the strangeness of this world and you’ll put it together in context and in realtime. Just like I did. In some ways, you’re in for a better ride than the pilots.

There are three things you need to know about me.

First, I’m a pretty average Joe. I’m 46. By any reasonable estimation, my life is more than half over. I live in the suburbs. I have a wife and two kids. I run the rat race every day about as well as the next guy. You wouldn’t recognize me if you ran into me in the grocery store.

Second, I always wanted to be an astronaut.

Third, I realized a few years ago that it was entirely up to me where between that baseline and that dream I would live each day of the rest of my life.

*****

Listen to this.

[ICAS hall noise.]

This is the sound of a magical zone in spacetime. It’s a room with about 60,000 square feet of floor space. It’s at the Paris Las Vegas Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, Nevada. I don’t know what happens in that room for the other 361 days each year. I’m not even sure that this room exists for the other 361 days of the year. But, for four days each December, it’s filled wall to wall with just about every airshow performer who’s active anywhere in the us and Canada. This is the exhibit hall at the International Council of Air Shows annual convention.

Standing at the back of the hall facing the doors way across the room, the Thunderbirds and the other Air Force TAC DEMO and static display pilots and leadership are off to the left against the far wall. The Blue Angels and the rest of the Navy and Marine Corps contingent are on the opposite wall. The Snowbirds are in the middle on this side. Sean Tucker, Mike Goulian, Skip Stewart, Patty Wagstaff, Bill Stein, Rob Holland, Billy Werth, Greg Koontz, Kent Pietsch, Andy Anderson, Bob Carlton, Gene Soucy, Scooter Yoak, Team Aerodynamix, John Klatt . . . every one of them is in this room right now. Hanging out. Booking next year’s appearances. Swapping stories. Doing whatever superheroes do when they get together each year between seasons.

I first came to this room in 2009 and I’ve been back each year since then. I’ve been very lucky and received media credentials each year. I interview people. I write blog entries. I did a full-up episode last year about what it’s like to attend the Airshows 101 all-day seminar. I’ve made contacts that have resulted in the T-38 ride and lots of other opportunities. And I’ve made it worth ICAS’s while by delivering pretty good coverage of the airshow industry.

But let’s be honest. I mostly go to stand around in that room. A room in which I don’t really belong, but am just enough of a poser and hanger-on to keep being invited back.

*****

I’ve admired fighter pilots and airshow pilots ever since I first read Sabre Jet Ace by Charles Coombs when I was in first grade. It was a Cold-War-era book, heavy on the propaganda and it used the words “commie” and “fella” a lot. I didn’t care. And neither would you. It was about flying F-86 Sabres. Still my favorite go-fast aircraft.

I’ve always wondered what it would be like to be up there in the box in front of the crowd. The only thing that I knew for sure was that it takes a huge commitment to get there. Especially if you’re not coming from a military background and have to do all of the training and get all of the resources yourself. And there are other commitments that compete. Food, shelter, house, family, career, and the list goes on.

But there’s also the responsibility that you have to yourself. It sounds cliché to say it, but you only get one chance at your life and you need to be mindful of whether you’re doing the things that are important to you.

Here’s the simplest way I know how to put it: What do you owe to your 10-year-old self?

[Fade in FOD.]

At that age, you might not have picked out your career or made some of the other big decisions, but you’ve developed some expectations. You have some sense of the grandness that your life is supposed to have and some sense that you’re going to do big things. These expectations are how you make it through sixth grade or whenever you have crises of confidence when you’re a kid. These are promises to yourself that it’s going to get better and that all this struggle with peer pressure, school, puberty, self-doubt, and angst are going to be worth it.

[Fade out FOD]

Because you’ll fly Sabre jets or be an airshow performer or walk on the moon. It gets better. That’s what we’ll do, kid.

But those promises begin to die almost before they’re fully formed. Your elders stop asking you what you’re going to be when you grow up because the real answers probably won’t be very interesting. High school commencement speeches are usually the last echo of those promises. And then we forget about them.

But what about your 10-year-old self? What about those promises? Is it enough that those promises got that kid through to become you today? Or does it have something to do with the three questions that kicked off this piece. Maybe they collapse into a simpler – and yet harder – question:

[FOD and me]

What do you owe to your 10-year-old self?

*****

Recently, by way of answering all of those questions, I decided to dig deeper into the airshow world. I’ve watched airshow ops from very close to the action and I’ve written about what it’s like to be a guy who’s watched airshow ops from very close to the action. But I had never been part of the action. Never been one of the actual actors. Never been the guy watched as opposed to the guy watching.

So I managed to talk my way into the world itself. On a weekend in March down in Florida, I went out and served as ramp crew and pyro guy for Mark Sorenson, Tiger Airshows, and The Ringmasters. That got me out at show center, blowing stuff up and putting out the airport when it caught fire. Then, in July, I did a stint as a team narrator at Battle Creek, picking up the mic and announcing an airshow act in realtime to a live crowd.

I learned that much of what I thought was wrong. I thought that the box was a noisy, exciting place. It turns out that out in front of the crowd – especially at show center – it’s mostly quiet, lonely, and intense. I thought that airshow acts spoke for themselves and that everybody understood the difficulty, skill, and showmanship on display. I learned that journeyman airshow performers mostly cast pearls before swine and it’s up to the narrator to use voice, music, and enthusiasm to reach out to the crowd and elevate its understanding of what it’s seeing.

But I also got a lot right. I’ve always sensed that every airshow performer made a personal journey into the waivered airspace. I’ve always sensed that every airshow performer comes to feel the high expectations of his or her peers and labors constantly under that professional pressure. Those thoughts were spot on.

*****

Just about every pilot in the exhibit hall at ICAS has flown under a numbered callsign at some point. I’m not talking about individual callsigns like “Maverick” or “Goose.” In fact, nobody gets cool callsigns like those. If you like your callsign, the system isn’t working right. Mine’s “Dogbag.” I duly hate my callsign, but it could be worse.

No, I’m talking about numbered callsigns that you use when you’re a part of a formation flight. Most people who fly multiple-ship demos didn’t start out as AeroShell 2 or Hopper 3 or Black Diamond 4. The Blue Angels’ boss sure didn’t fly as “boss” on his first formation sortie. Each started as something else. Usually a flight callsign assigned by the wing or the squadron and then your number in the flight. I asked a few people in the ICAS exhibit hall to just speak the first numbered callsign that they ever flew.

[Callsign montage]

There are household names among those who spoke those callsigns there in the hall at ICAS. You’d recognize those names. But I think I like just leaving it at the voices themselves without identifying the pilot. They all mean the same thing.

Most of the pilots at ICAS immediately recalled their first numbered callsign. They didn’t have to think that hard to remember them. It confirmed another thought that I’ve harbored for some time. You remember the first time you launch in a flight of aircraft in which everyone else in the flight trusts you to fly close to them and not hit them. You earn the privilege of your place in the flight and then you work even harder to keep it.

*****

The TG-7A is the military variant of the Schweizer SGM 2-37. It’s an all-metal motorglider that’s basically a Piper Tomahawk firewall-forward and, aft of there, it’s a Frankenglider combination of wings from the SGS 1-36 and the tail of the SGS 2-32. It has a Lycoming O-235-L2C engine on the nose, putting out 112 hp. It’ll cruise at around 95 mph, stall at 48 mph, and do 135 mph in a dive before you redline the airspeed indicator.

Schweizer designed it for the US Air Force Academy and the academy took delivery of nine copies between 1982 and 1988. Six of those remain flyable and the Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum operates three. The Tuskegee aircraft were surplused out from the academy in 2003 and the museum uses them to give Young Eagles rides, train scholarship students to fly, and promote the museum’s missions. Because of their history with the academy, they’re technically warbirds.

In March of last year, with maybe two hours of TG-7A with John Harte, I went to a FAST formation ground school. The museum organized the school for its pilots who were interested in flying in airshows.

FAST is an acronym for the Formation and Safety Team, a self-regulated sanctioning organization that supervises formation flight qualifications. The FAA doesn’t deal with formation flying, other than to say that the pilots in command of all aircraft in the flight have to agree to fly in formation and that you can’t fly information while carrying goods or passengers for hire.

You care about FAST for two reasons. First, the organization has a huge amount of tribal knowledge about how to fly aircraft in close proximity and do it safely. Second, if you want to fly within 500 feet of another aircraft in the waivered airspace of an airshow box, you have to have a “FAST card” saying that you’re qualified according to FAST’s standards. That qualification requires – for a wingman – a ground school, a written exam, 10 hours in formation, and a checkride.

I went to the ground school because it seemed interesting. And because nobody I knew outside the airshow community had a FAST card and I thought that it would be pretty cool to have one someday. I didn’t for a minute think that I’d ever get 10 hours of time in formation, but you never know.

I had been in formation once or twice with others flying the aircraft. I already knew that it was difficult, but the ground school opened my eyes to just how much is involved. There are radio calls, hand signals, preflight briefings, post-flight debriefings, roles, responsibilities, emergency procedures, and more.

Later on, in May, as I was training for my commercial glider rating, I went along with John Harte and Mark Grant on a day-long flight. John and Mark were actively pursuing FAST cards at the time. The plan was to turn the props at Detroit City Airport (KDET) at sunrise and head to Mason Jewett Field (KTEW) in Mason by a circuitous route and practice formation along the way.

We hit Detroit Metro Airport (KDTW) and the tower gave us the entire eastern side of the field. I sat in the left seat (the passenger or instructor seat in the TG-7A) while John and Mark flew the pattern in formation, making echelon takeoffs and landings on Runway 3R. With 59.5 feet of wingspan, TG-7As need at least 150 feet of runway width to take off or land in elements and Metro has the runway width.

I discovered on the short flight to Metro that we were going to fly pretty close. And then I realized that maneuvering in the pattern is even trickier. Many pilots spend a lot of time in the pattern perfecting landings when they only have to worry about the aircraft they’re flying. Taking off, flying the pattern, and landing in echelon is another level of skill entirely.

We hit Willow Run (KYIP), Richmond Field (69G), and Howell (KOZW) in much the same way before getting to Mason, where we met up with Dan Schiffer, our FAST check airman.

Dan had never seen us fly and had never even seen a TG-7A up close. We loaded up with Dan and Mark in one ship and John and me in the other. An hour later, both Dan and I had a pretty healthy respect for the formation skills on display, Mark and John had some work to do before qualifying for FAST cards, but we all left with a much better idea of what we needed to work on.

For brief periods during the flight with Dan, I got to fly. A little bit on the wing and then a little longer as lead. On the wing, I was completely overloaded. Power, pitch, roll, and yaw, all relative to another aircraft there in the windshield. I felt like I was trying to fly while wearing ski boots, oven mits, and blinders. Flying lead, I flew very mechanically, trying to keep a precise altitude and airspeed and otherwise provide the stable platform for the formation like the FAST handbook says. It was one of those sessions where you find it hard to believe that you can be that exhausted after doing something where you’re sitting down the whole time.

I’m a reasonably competent stick and rudder guy. I fly upside down for judges. Not often and not well, but I do it. When we got back to Detroit City, I had my man card buried deep, deep in my pocket. I had just spent an entire day figuring out just how much I didn’t know about formation flying. And, by extension, just how little I knew about airshow flying.

*****

The spring continued and then turned into summer. I soloed the TG-7A later in May. I continued to train with John for the commercial glider rating. On weekends, the hangar would empty out as the Tuskegee Demo Team took the aircraft to airshows around the region. On weekdays at the crack of dawn or after work, John and I would grab an aircraft and head to Grosse Isle (KONZ) or Romeo (D98) or elsewhere and train for the checkride.

By late June, just before the Battle Creek airshow, I was solo-rated in the TG-7A. The Tuskegee airshow team was taking all three aircraft to the show to perform. I arranged to be the narrator for the show, which got me a ramp pass and better access to the rest of the show. And, because I was driving, having an extra vehicle there for the team would be helpful.

On Wednesday before the show, I got a call from John. John was also one of the guys who were going to fly the show at Battle Creek. John had business in Detroit on Friday and couldn’t get away to ferry his ship to the show. John asked me to ferry the aircraft on Friday morning so it’d be there in time to fly the practice demo. I’d leave my car at Detroit City and John would drive it over on Saturday morning.

Friday morning, I showed up at Detroit City Airport before dawn. I had a handheld GPS and my charts and was planning on preflighting and launching solo to head to Battle Creek. The other two guys would launch as a two-ship formation and meet me there.

I got the hangar doors open and was just about to figure out which of the three aircraft I should take, when Mark Grant and Joe “Jo-Jo” Cartier drove up. We pulled all three of the aircraft out and I got N763AF. I completed my preflight inspection at about the same time as Mark and Joe. I walked over to ask about their plans.

Mark turned to me and said, “Steve, you’re flying 3. You’ll be on the left.”

I hadn’t expected that. I had only walked over to ask them about their plan so that I could give them plenty of space and pick an altitude other than the one at which they’d be flying. Turns out that I had walked into a formation flight briefing.

“You sure about that?” I said.

Jo-Jo piped up. “Just get over on the left side, fly smooth, and don’t hit anybody.”

It became apparent that these guys were serious and I was about to be part of a three-ship cross-country flight with an arrival at an airshow site.

If I’m a superhero, I’m a very minor superhero. I have powers only akin to the ability to summon elevators or release pretzels hung up in a snack machine. Useful, superpowers, mind you. But not dramatic.

Running this podcast for seven years has given me some pretty cool opportunities in military jets and other aircraft. It’s not uncommon for fans or friends to be under the impression that I’m a much better pilot than I am. And they offer me opportunities that are very flattering and very cool, but often are beyond what would be smart to accept or try.

This has resulted in the development – under stress – of a minor superpower that I had no idea that I’d ever need: The ability to make a judgment call in seconds about whether a given situation is a great opportunity to challenge myself or a foolhardy invitation to do something stupid or for which I’m in no way prepared.

Superpower or confirmation bias plus ego? I say superpower.

In any case, I hemmed and hawed for a couple of moments, then shut up, got in the aircraft, and started up.

From the time we released the brakes to taxi, I was all eyeballs and elbows. I again had that feeling of wearing ski boots and oven mits and looking at the world through a soda straw. I taxied where I thought I was supposed to. I went through my checklists twice. Then we were all lined up on the runway.

Mark, as lead, made his takeoff run. Joe started rolling as soon as Mark lifted off and I followed suit when Joe lifted off.

One last look at my gages to make sure that the aircraft was happy, then I turned west to chase down the other two aircraft. Joe was already sliding into place on the right wing. I kept the throttle firewalled and pointed my bird at the other two.

It’s one thing to be in an aircraft with John or Mark and either get constant coaching or know that you can get it if you need it just by asking. It’s quite another to be all alone in an aircraft looking out the windshield at a piece of air slightly behind and to the left of lead and knowing that you’re supposed to put your aircraft there and keep it there.

It seemed to take forever to catch up to the flight. The other two aircraft stood still in the windshield and very slowly started to get bigger. Then they got bigger very quickly. I pulled power. They got smaller very quickly. Full power again. Again they got bigger way too quickly. This continued for about 10 miles.

Who am I kidding? This continued for more like 100 miles. I kept my distance initially and worked my way in. I could see Jo-Jo over to my right in the No. 2 ship, much closer in and much more stable than I was, so I knew where I was supposed to be symmetrically on the left. In fact, it’s 3’s job to be 2’s mirror image and make the formation look good. Even if 2 is ahead of the bearing line (“acute”) or behind the bearing line (“sucked”).

I did not do a very good job of this. Over Plymouth, I was twice as far out as I should be. Over Ann Arbor, a little less than that. By Jackson, I was maybe down to one and a half times as far out as I should be.

By then, we were on our air-to-air frequency and I got pretty consistent commentary from Lead and 2, either calling me “4” or complimenting me on what a great missing man formation I was flying.

Every time I went to adjust position closer, I’d give it some more throttle and a little right rudder and wait. Nothing for a second or two. Then lead’s aircraft would start drifting closer, slowly at first, and then at a higher rate. I’d try to arrest the rate of closure, but I’d start too late (forgetting that that same lag would happen in the opposite vector) and end up with a much more abrupt control input to move back away again.

If I got low, I’d pull up, but wouldn’t add throttle to counteract the additional drag. If I was high and trying to get back down, I’d pitch down, but forget to pull a little throttle and I’d find myself about to overrun lead. Once, I hung out the dive brakes for a moment to kill that forward movement.

When Lead called up ATC about 20 miles out, there were other arrivals going on, so the tower told us to fly circles a few miles north of the field. Lead shook the formation out into loose trail, which put us in line one after the other. We orbited for maybe five minutes. I tried to keep 2 on the horizon and keep my spacing from 2 the same as 2 had from Lead. It was mesmerizing. If I had the position just right, 2 would just sit there in the windshield motionless. When the circling turned me east and into the sun, 2 became a fuzzy dark spot in the bright haze for maybe 90 degrees of turn. And, having done so for a few minutes looking only at 2 and Lead and the horizon and maintaining 30 degrees of bank, your vestibular system will tell you that you’re flying straight and level, all visual appearances notwithstanding. It’s enough to give you vertigo when you roll out if you’re not careful.

The tower cleared us for Runway 5R with a right break and, the next time around the hold, Lead took us straight in, heading for a spot directly over the numbers. In trail, I could now take my eyes off of Lead and 2 for a few seconds at a time. I pulled the carb heat, pushed the mix to full, flipped on the fuel pump, and checked my systems. And I could get a good look around for the first time since joining up.

[In the Sky]

The show grounds were laid out below and to our left. The same show grounds that I had walked at a kid in the 1970s and the same show grounds to which I had come back six ago, when I started the whole podcast thing. I was approaching the runway from which I had departed in an F-16 with Thunderbird 8 four years ago. And I was doing it in a three-ship formation with an airshow team.

Suzanne Brindamour’s In the Sky (The Barnstormers’ Theme) from the soundtrack of the film, Barnstorming, came unbidden into my head and played. Indeed, we in our yellow longwing aircraft were barnstormers, arriving from our mystical home somewhere over the horizon to fly for an airshow crowd. I had stood on the grounds at innumerable airshows watching the arrivals. Now I was one of those arriving.

Lead arrived over the runway threshold at cruise speed and called the break. He rolled to 60 degrees and rapidly disappeared to the right. Three seconds later, 2 did the same. I counted to three. My turn. Right stick and rudder to 60 degrees of bank. And pull.

Two Gs registered on my cheeks and pulled my headset down on my head. I divided my attention between the airspeed indicator and the horizon, then started looking for Lead and 2. There they were out in front of me circling to land and well-spaced.

I keyed the mic. “Spacing good.” And followed them around and started including the runway threshold in my scan. “Tuskegee 3, right base, gear down, full stop.”

We shut down on the ramp. Mark and Jo-Jo immediately caught a ride to the briefing at the other end of the field. I stayed to manage getting the aircraft refueled and make sure that they were ready to fly the practice demo in a few hours.

That done, I fired up my iPod, cued up the Barnstorming soundtrack, and just walked around the ramp for awhile. Stephen Force, the great poser, had returned to his home show. And he had done it in a three-ship flight of performing aircraft. I had taken a mental snapshot up there on the overhead. Banked over 60 degrees, hanging in midair, just about to pull. My home field just below me with the show grounds spread out and awaiting an airshow crowd. It felt good.

*****

Mark French and John Harte also arrived at the show and, in combination with Mark Grant and Jo-Jo, they flew all of the actual demos. I narrated all three of the team’s demos that weekend.

But I did more than that. Team Tuskegee makes it a point of flying as many media people and VIPs as possible and therefore gets up a lot before and after the show. If Team Tuskegee flies your show, it’s not uncommon for the team to show up at 0700, meet the media or other riders, and have logged an hour of flight time before the rest of the performers even start heading into the briefing. And, whenever there were two or fewer riders and one of the demo guys wanted to sit one out, I launched with the team and flew as 3.

Truth be told, at that point, the team could do more outside the waivered airspace than it could inside the waivered airspace during the show. Because no one had a FAST card yet, the team couldn’t fly formation in the box. But, before and after the show, the team went nuts, taking every opportunity to practice. Taking along media or VIPs is always good for the show and, burning something like five gallons of gas per hour per aircraft, the team costs the show next to nothing even if the show was putting gas in the aircraft. The entire Tuskegee TG-7A team burns less gas in an hour than a single T-6 does in 20 minutes at full rich. And, as a non-commercial pilot at that point, I paid for my own gas when I flew.

Side note to organizers of airshows within 200 nm or so of Detroit. You really owe it to yourself to have the Tuskegee Airmen Gliders fly your show. There’s nothing else like the team’s demo on the airshow circuit anywhere in the world and the team bends over backward from sunup to sundown flying media and VIPs and keeping your skies full of interesting stuff. E-mail me and I’ll put you in touch with our airshow coordinator.

There at Battle Creek, I flew my first formation in the pattern at the controls. Echelon takeoffs and landings. Formation passes in fingertip, echelon, and trail. And we’d even take the aircraft up to five or six thousand feet MSL, shut the engines off, and fly formation as power-off gliders. My first time doing that, too.

After the demos on Friday and Saturday, I handed the microphone back to the regular announcer as soon as the last aircraft was wheels-down and out of sight and hurried back to the ramp and sat in on the team’s debrief of the demo. A debrief always starts off with the highest-numbered wingman and ends with Lead. They deconstruct everyone’s performance, identify any safety issues, and figure out what went wrong. And identify the things that went right. They even asked me questions because I was narrating and had a commanding view of the demo from the announcer’s stand. Very much the picture of an ambitious newer airshow team figuring out from the ground up how to operate safely and professionally.

On Sunday, weather was on its way toward the field around show time. The team flew the demo and then departed to the east to beat the weather and get the birds home. I followed an hour later in the car. Yeah, I was jealous of the guys in the aircraft who were probably passing Plymouth by then. I had had a taste of what it was like to fly with the team and I liked it. I liked it more than a little bit.

A week and a half later, I climbed back into a TG-7A and rocked out the commercial checkride. The ride is covered in the second of the two glider rating episodes. You can check it out in the Airspeed feed.

And then things accelerated even more than expected. A few days after word circulated through the organization that I had a brand new commercial ticket in my hand, I got a call from Jo-Jo.

“Dogbag! We’re flying the Rogers City show August third through the fifth.”

I pulled out my calendar and began figuring out whether I could make the time to go narrate for the team. And then Jo-Jo dropped the bomb.

“You’re flying 3 in the show. Welcome to the team, buddy!”

*****

A lot of pilot wisdom finds voice in Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff. In the test pilot and astronaut culture, what drove these guys wasn’t so much fear of getting killed or maimed. It was the fear of screwing the pooch. Of performing poorly. Of not making the grade.

This isn’t a justification for wild abandon. Quite the contrary. In the formation and airshow community, safety and risk management are the primary driving forces, bar none. The performance standards are all based on safety. If you perform to the standards, you’re safe – or as safe as you can be engaging in aviation.

The point I’m making is that you reach a stage at which you no longer care so much about not getting killed or hurt for its own sake. You care about it because to get killed or hurt – or to hurt somebody else – would be a failure to perform to standard. To screw the pooch. To let down your teammates and the community of airshow performers. This is the highest and best use of peer pressure.

Airshow pilots, especially formation pilots, have a saying. “Perfection is expected. Excellence will be tolerated.” They mean this from the bottoms of their hearts.

*****

Michiganders are famous for pointing out locations in the lower peninsula of the state by making the mitten shape with their right hands. You can also add the upper peninsula with your left hand, but I don’t recommend trying it unless you’re actually from Michigan. There’s a potential for injury, especially if you’re from Ohio. We also do Florida, but this is a family podcast.

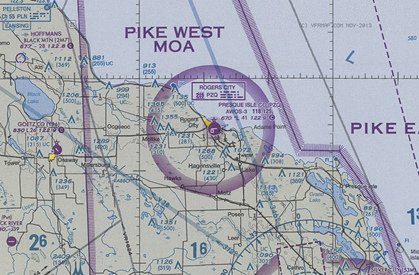

Using your right hand with the palm facing toward you. Rogers City is pretty close to the tip of your right index finger. Detroit is, of course, on the lower right in the meaty part of the heel of your hand below the thumb. A straight-line flight necessarily takes you over Saginaw Bay, which is between your thumb and the rest of your hand.

Jo-Jo and I arrived at Detroit City, preflighted, briefed, and rolled to the hold-short line. The tower cleared us and we took off in sequence. I had trouble almost immediately.

Jo-Jo’s aircraft was performing a lot better than mine. I tried to keep up in the climb, but got pretty slow and had to let the nose come down. That made me faster forward and lower than Jo-Jo. But I got that resolved soon enough and we climbed for miles. Soon, we were up around 10,500 MSL. Jo-Jo shook me out to route and we both checked our systems. All happy, we went feet-wet over Saginaw Bay.

At that altitude, and being gliders, I don’t think that we were out of gliding distance from shore for very long, if at all. But it was still the longest over-water leg that I have ever done. About 30 miles. It’s times like these that flying formation is helpful to take your mind off of the long stretch of water between you and land. And, for that matter, between you and a proper landing field if you can glide to shore.

Just past the bay, a cloud layer spread below us. We could certainly have stayed VFR over the top, but there was no guarantee that we’d be able to find a hole over our destination. So we descended and slipped under the layer just as we went feet-dry past the bay. We stayed VFR, but not by much and skirted a few antennas as we wound our way up the coast.

Jo-Jo hates flight suits. I can begin to understand that. It’s not hard to overheat when you’re in a Nomex zoom bag in the sun all day. But the team tried to look pro by wearing flight suits for show arrivals, when we perform, and when we make appearances. So he wore shorts and a tee-shirt for the hop over the bay. The plan was to land at Alpena, a little south of Rogers City, so Jo-Jo could change into his zoom bag. I, of course, wore my zoom bag the whole time. We probably don’t need to talk about how I actually wear it around the house and even to the grocery store if I can get away with it.

The Alpena airport and adjacent land is home to the Alpena Combat Readiness Training Center. Some rather heavy hardware occasionally comes through. As we arrived, with winds out of the south, a KC-135 Stratotanker was taxiing around on the north side of the airport. The tower cleared us to land on Runway 1. That meant a tailwind component of something like seven knots. Jo-Jo accepted it and we put them down after a left overhead break. It was a little sporty and I was well and truly hauling the mail landing downwind, but Jo-Jo gave me plenty of room by landing far down the runway.

A change of uniform for Jo-Jo, a resupply of coffee for me, and we launched for Rogers City. The ceiling continued to be low and ragged. We ran scud the rest of the way, keeping Class G VFR cloud clearances and avoiding cumulus jack-pinius. At least visibility was good.

*****

It has been said of me that what I do is similar to what George Plimpton did in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Besides being very erudite and born into a family with some money, Plimpton was a more or less regular guy. A writer and journalist.

Hunter S. Thompson gets most of the credit for participative journalism for books like Hell’s Angels. But Plimpton had a major role in it, too. Even before Thompson published Hell’s Angels, Plimpton pitched against the National League All-Star lineup in 1958 and captured the experience in his book, Out of My League. He also went three rounds each with boxing greats Archie Moore and Sugar Ray Robinson while on assignment for Sports Illustrated. In 1963, he went to the Detroit Lions’ training camp as a rookie quarterback and captured the experience for Sports Illustrated and in his book, Paper Lion. Paper Lion was made into a film in 1968 starring Alan Alda and Alex Karras. And, not least, Jonathan Coulton wrote an ode to Plimpton called A Talk with George. The JoCo song is really wonderful and I hope you go listen to it and pay JoCo some money so that he keeps writing stuff like that.

There’s a scene about halfway through the film of Paper Lion. Plimpton (played by Alda) is reacting to a prank played on him in the dorms by his teammates, who have discovered who Plimpton is and what he’d doing at the training camp. He’s talking to Alex Karras (playing himself) when John Gordy, an offensive guard, (also playing himself) steps into the doorway. Gordy tells Plimpton that he respects what Plimpton is doing, but that Gordy is unwilling to play for him. Gordy explains that this is all well and good for Plimpton as a poser who’s going to write about the experience. But this is Gordy’s profession and he doesn’t want to get hurt if George screws up the offense. “Ligaments don’t heal, George.”

It’s okay to be a poser when you’re the guy in the back seat of the aircraft just along for the ride. But being an actual performer takes things to the Paper Lion level. And then way, way beyond.

Diving into the box as a performer is a binary thing. You’re an airshow pilot or you’re not. Even if you yourself are willing to find out the hard way that you’re not good enough, you don’t have the right to make that decision for your teammates or for the crowd.

Nobody stopped in my doorway and gave me a John Gordy talk. But nobody needed to. I propose to fly very close to other aircraft. I propose to fly in waivered airspace as close as 500 feet from tens of thousands of people. The guys flying the other aircraft, the air boss, and the crowd are all going to depend on me to be where I’m supposed to be and have ample supplies of altitude, airspeed, and ideas at all times.

I admire what George Plimpton did. I’ve used his model to great advantage. It has served me very well up to this point to be a poser. But this is different. You can’t Plimpton this. You’re an airshow performer or you’re not. If you’re going to dive into the box with the intent to commit aviation, you had better be an airshow performer.

*****

We arrived at Rogers City shortly. Rogers City is visible from space on account of the huge calcite mine on the Lake Huron shore just south of town. We flew along the shore over the mine and scoped out the show box over the water in front of the marina. The box was marked with buoys and Jo-Jo shook me out to route so I could steal glances at the markers and the general environment.

After loitering a little more to reconnoiter, we formed back up tight and flew a low pass at the Cat III line to let the locals know that Team Tuskegee had arrived. Climbing back up to 800 AGL, we headed for the airport, executed a left break over the numbers on Runway 9, landed, and taxied in.

The airport is a couple of miles south and inland from the box, just west of the calcite mine as you go inland. I had already printed out a Google satellite map of the surrounding area and drawn glide rings from various altitudes with various wind assumptions. For most of the demo, we’d be at 500 ft AGL so, if one of us lost an engine, he wouldn’t be able to glide to the airport and would have to ditch in the lake. There was a set of baseball diamonds just outside of town, but that was really the only flat and clear area nearby other than the airport. Generally speaking, if I lost the engine at an altitude that precluded gliding back to the airport, I’d prefer ditching close to shore to risking hitting a tree or fenceline.

We pulled up to the pumps and set about refueling.

I lived in northern Michigan for seven years from 1977 to 1983. I understand the people who live there. They’re plain-spoken and straightforward. You sometimes have to remind yourself that there’s almost never a subtext or implication in anything a northern Michigander says. Every word means what it means, nothing more and nothing less. And, if a northern Michigander asks you a question, it’s because he actually wants to know the answer.

All of which is by way of explaining the very first question out of the mouth of the show volunteer who met us on the ramp: “Hey. Why ain’t you black?”

I get it. I truly do. The aircraft all say “Tuskegee Airmen Glider Club” on the noses. And even if many Americans don’t know about the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group, which was composed of the first black pilots to fly for the US armed forces, the film Red Tails had recently played in theaters.

In case you haven’t met Jo-Jo or me or seen pictures of us – and in case you can’t tell from my speech – each of us is as Caucasian as the day is long. We sometimes have to explain that our TG-7As are owned and operated by the Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum and that, when the aircraft aren’t at airshows raising awareness of the museum’s missions, they’re back in Detroit being used to train scholarship students and give Young Eagles rides to kids from Detroit’s overwhelmingly African-American neighborhoods.

Each aircraft bears the names of two Tuskegee Airmen – one on each side just below the canopy. Additionally, each pilot like me is also always on call as a safety pilot. If any Tuskegee Airman wants to fly one of the TG-7As, I’m one of the guys who would climb into the left seat and fly with him. I make a fair amount of hay on this show about being a guy who has scrambled hard to get opportunities to fly. But I think I’d have to put that card deep, deep in my pocket if I ever had the honor of flying safety for a Tuskegee Airman. I haven’t been called upon to do that yet.

So we have a genuine connection with the Tuskegee Airmen and the logo on the fuselage of the aircraft is well-earned. Every one of us is honored almost beyond words that we get to play this role in telling and perpetuating one of the most important stories in American history.

But – yeah – we have to explain things on occasion. Usually, when I land at an airport and I sense that a bystander is brewing the obvious question, I try to beat him to it by immediately walking over before he gets to ask the question and saying, “I know what you’re thinking. I look a little young.” It’s a great introduction and it provides me an in to talk up the museum and its mission.

*****

There’s another element of that Right Stuff culture that’s important. Nobody told me this, but I thought a lot about it in by search-and-rescue training and aerobatic competition and know in my bones that it must be true.

It’s important to pay attention to risk. I’m a huge fan of avoiding trouble in the first place through the use of my superior decision-making skills, thus making it unnecessary to rely on my superior pilot skills.

Many different kinds of aviation involve many different kinds of risk. Some would call mowing the lawn at 90 knots and 1,000 feet with a notch of flaps – or descending to 500 feet for a closer look – too risky. After all, if you lose the engine, you’re going to make contact with the ground somewhere within two miles of where you lost thrust. If that’s in a place with dense forest or an urban area, that’s really problematic. It’s also exactly the profile that I sometimes fly when I’m flying search-and-rescue for the Civil Air Patrol. I understand those risks, I mitigate them where I can and I train to deal with them where I can’t mitigate them. And, after lots of consideration, I accept those risks. When I launch, I spring-load for the risks, leave the worry on the ground, and go fly the mission.

Flying in an airshow involves additional and different risks. You’re low. Sometimes, if it’s a displaced show, you’re over water or other unlandable terrain. There’s a crowd line that cuts off something like half of your options geographically. You might be flying very close to someone else. Someone else might be flying very close to you. There might be more than one someone else. You’ll likely be in non-standard attitudes and you’ll be that way very close to the ground. It’s a bag of risk that you have to know everything about, develop the skill to address if the worst happens, and accept everything that you can’t mitigate with training and skill.

Just like SAR, you need to figure out what your risks are and what you can do by way of training and preparation to mitigate them. Then you decide whether you’re going to fly this airshow.

There’s a sense of peace that follows making that decision. You’ve made that call and there’s no reconsidering it until you’re again on your home ramp putting the aircraft away. It allows the past and the future to vanish around the periphery of your vision and it allows you to be entirely in the present moment. One with your aircraft. Have you ever had your aircraft disappear around you and just been there in space and time, maneuvering by mere thought? It happens. If you’ve ever had it happen to you, you know how powerful that peace and flow can be. It empowers the greatest performers of our species.

All of this results in a very important balancing act. You can be too cautious. Risk analysis degenerates into worry. And you end up not doing things that you should have and you regret it later.

On the other hand, you can be reckless. Think really hard about how good that peace feels. In case you were wondering, I was not kidding about the aircraft disappearing and being utterly present in flow. It happens. If comes about by a thought process. It can also come from a faulty thought process. It can come about because the pilot wants that flow so badly that he or she will delude him or herself to get to that peace. And there’s not much difference between the two kinds of peace. Very little objectively. And absolutely none subjectively.

Whatever your calculus, when the time comes, you decide that you’ve done all you can to identify every risk, train for it, and be spring-loaded against it. And, most of all, you decide that if something bad happens and not even your best planning and hardest training can save you – that’ll be okay.

That’s freedom. And flow. And peace.

*****

At most airshows, Friday is a practice day. Most airshow waivers require that each performer have practiced his or her performance within some period prior to the show proper. Usually 15 days or so. At the bigger shows, the practice runs pretty much like the regular show days. Airshow organizers have figured out that they can call it “media day” or “sponsor appreciation day” or something else original and essentially extend the show by a day.

The larger shows usually run the practice day just like a regular show day in the same order as Saturday and Sunday. At smaller shows, like Rogers City, the waivered airspace goes up and teams simply call up the air boss when they’re ready to go practice.

That was the case on Friday. After refueling, offloading our bags, getting the keys to the rental car, and going through the FAA inspection of the airmen and aircraft, we briefed and climbed back into the aircraft to practice.

We got a call from John saying that the other TG-7A had a rough-running mag. He got as far as Saginaw before turning back to have the mag looked at. Thus, we decided to practice as a two-ship.

The Tuskegee demo that season went something like this. It’s an air start, which means that we launch and orbit somewhere behind the crowd until it’s time to take the box. We’re outside the waivered airspace and behind the crowd at that point, so we’re usually in trail or right echelon formation, making left turns.

When the air boss calls us in, we separate out with lead 500 feet to the left of show center, 2 lined up on show center, and 3 500 feet to the right of show center. Lead is a few hundred feet ahead of 2 and 3, who are line abreast. We approach from behind the crowd at 1,000 AGL. At the crowd line, all three aircraft reduce throttle and descend to 500 AGL. Once we’re at 500 AGL, we power up and fly level for a few seconds, then lead calls the break.

At the break, Lead breaks right and 2 and 3 break left. This puts us immediately into a right-handed racetrack pattern around the box. We separate enough so that, at any given time, no aircraft is within 500 feet of any other. At any given time, at least one of the three ships is wings-up in a turn, which is pretty dramatic-looking when you’re yellow and have 59.5 feet of wingspan to show off. In most waivered airspace, they give you up to 70 degrees of bank before you’re technically aerobatic, so we can really go to a full 60 degrees with a margin for error.

After a few trips around, Lead calls for the figure-eight. That’s pretty much what is sounds like. Three TG-7As flying a figure-eight centered on show center. This gives the long-lens camera folks at one end of the field an angle different from that of a racetrack pattern. During this time, the narrator is describing the TG-7As for the crowd.

After a few times around the figure-eight, it’s time for 3 to show off. Lead calls “Tuskegee Tornado.” Lead and 2 circle up to 1,500 AGL or so. If they work it just right, they’re on opposite sides of a circle and they look like their wings are locked. It simulates what engineless gliders do when they’re riding the same thermal. They call it a “gaggle climb.” But “Tuskegee Tornado” sounds better. The narrator describes thermaling and gaggle climbs.

As Lead and 2 are climbing, somebody has to keep the ice-cream lickers’ attention and that’s 3’s job. 3 dives for show center from wherever he is at the call. Leveling out just over the runway, he gets adequate airspeed to climb, then (ideally, just past the end of the crowd line) climbs 350 feet at 80 mph or better. If you carry a little smash into your dive to show center, you can be around 100 mph at the pull for the climb and get that 350 feet pretty quickly while keeping enough airspeed for what comes next.

And what comes next is pulling the throttle to simulate an engine failure, pushing for 80 mph if you don’t already have it, burying the wing away from the crowd down to 45 to 60 degrees of bank and pulling for 210 degrees of turn back to the runway. It simulates a rope-break right after takeoff if you’re being towed in an engineless glider by another aircraft. The narrator explains this and also explains “The Impossible Turn” in airplanes, giving a stern “don’t try this in anything but a glider” warning.

If it were a real engine failure, 3 would simply glide back to the runway and land. For the demo, 3 leaves the engine back at idle all the way around that big, dramatic turn, then powers up to build smash to get back down to show center at around 100 mph to do it again in the other direction. Ideally, 3 gets at least two passes like this and maybe three before Lead calls “Tuskegee engine out.”

At that point, Lead stops circling and 2 pulls line abreast. Lead and 2 cut their engines and prepare to come back in true glide mode. The next time 3 is headed back for show center, he leaves the engine at idle after the turn, sets up for a good turnoff point, lands, and gets off the runway, calling clear when he is.

Lead and 2 then come back in and land, ideally preserving enough smash to roll to a turnoff and clear the runway before restarting their engines and taxiing back in.

When the team flies the demo with the museum’s T-6 Texan, the T-6 does a series of passes in front of the crowed immediately before the TG-7As come in over the crowd. We break out of the show hold and start heading for the crowd line when the T-6 calls on approach for his last pass. The T-6 then goes out a couple of miles and circles while the TG-7As do their routine. As Lead and 2 land engine-off, the T-6 comes roaring on over the top of the two TG-7As at the speed of stink with the prop set for noise. Really dramatic and a wonderful contrast between silence and noise.

*****

Jo-Jo and I launched and headed for the box. It was both strange and exciting. I stayed on Jo-Jo’s wing outside the box until it was time to approach the crowd line. Then fanned out to the right over the town as we approached inbound to the box. With the distance, I could look around and see the box markers, the crowd line, and the surrounding area. I committed as much of the picture as possible to memory.

As I floated in over the shoreline, getting ready for the call for the break, I imagined the shoreline filled with people. I imagined a frequency buzzing with other performers recovering after leaving the box or launching to get to their show holds. I imagined everybody else in the air and on the ground utterly occupied with his or her own tasks and depending on me to be where I was supposed to be, when I was supposed to be there.

We flew the routine a couple of times, just getting the sight lines in place. I didn’t leave enough room behind Jo-Jo at the initial break, so we debriefed that in the air and got it right.

We landed and I went about tying down my aircraft. Jo-Jo took a VIP for a ride and then came back in and did the same.

We headed down to the marina where they were feeding the performers. The airshow program consisted of Kevin Copeland, us, and Team RV (now known as Team Aerodynamix).

Kevin flies a Super Decathlon. I met him when he flew Northwestern Michigan University’s Super D down to Romeo for the second Acro Camp movie. He has since bought his own Super D and he performs a solo aerobatic act. He was flying as many shows as he could in order to get his qualifications and get his waiver extended lower and, eventually, to the surface.

Term Aerodynamix was and is something else entirely. They fly 11 experimental RVs aerobatically in formation. That’s a lot of aircraft in the air at once and, when they’re all running smoke, that’s a lot of excitement happening all at once. With three flights, there’s almost always something going on at show center.

*****

We stayed at The Captain’s Quarters, a little motel on the highway a few miles from the airport. A lot like the little ma and pa places at which my family used to stay when we vacationed up north. Jo-Jo and I dragged a couple of plastic lawn chair over into the grass, lit up cigars, walked through the demo a couple of times, then talked awhile before turning in.

*****

I woke up plenty early. Rogers City is a place where you can get the farm report on more than one TV station and I let that play as background while I showered, put on my flight suit, and hit the parking lot to meet Jo-Jo.

John called to say that they were going to have to work on the mag and that he wasn’t sure whether he’d be able to get up to Rogers City in time to fly the show. At the airport, we untied the aircraft, did our preflight inspections, and then headed over to the briefing.

The air boss for the Rogers City show was Bob Buttleman. I knew him because he had been my check pilot for my seaplane rating a couple of years prior over in Traverse City. Unlike other briefings I’ve attended, this show was very small, so we just stood around one of the picnic tables there in the main hangar.

Kevin would lead off with his solo demo. Jo-Jo and I (and John if he made it up in time) would follow, then Team RV would take the airspace. We talked about the box frequency, what we’d do if we lost comm, where the emergency services people would be, and all of the other material that you need to cover. Then Bob wished us a safe show and left for the waterfront. I gave the narrator the background information about us and the aircraft, then wandered out onto the ramp.

*****

When it came time to fly, we started up and taxied to the end of the ramp closest to the threshold of Runway 9. As I did my run-up. I saw Kevin on his takeoff roll. He rose off the runway and turned left, heading straight to the box. Shortly thereafter, our runup complete, I lined up on the runway behind Jo-Jo, then closed my dive brakes to indicate that I was ready.

We powered up and took off in sequence. I formed up on Jo-Jo’s wing and we orbited about two miles inland from the box and waited for Kevin to complete his demo. I couldn’t see anything in the box because I was on Jo-Jo’s wing, but I could hear the air boss and Kevin talking and, soon enough Kevin wrapped up and the boss called us in.

Jo-Jo gives me a couple of positioning comments. As we come in over the shoreline and began to dive into the box, I rudder out to 500 feet abeam and a little behind.

This is it. The audience is real. The airspace is real. I’m all alone in my aircraft and lead, the airboss, and the audience all expect me to deliver.

I can see the crowd line stretching out to either side. A few thousand people – among them guys a lot like I was a few weeks ago. The box markers disappear under the nose. Last check of the gages and they’re all good to go. Look left and check position. We pull out of the dive at 500 feet and then hang in midair for an endless moment. Then . . . It’s on.

[Tuskekee break]

I crank it over and peel out of the tornado and – leaving lead behind – I angle for just this side of show center and push the nose over, heading for the wavetops.

The box is lonely and quiet, just like before on the ground. But it’s also electric. There’s no fear. For that matter, there’s no division between my will and my wings.

I level off above the wavetops with the airspeed in the yellow.

[FOD: This is what I heard you promise.]

[Me: This is what I promised.]

[FOD: I have the flight controls.]

[Me: You have the flight controls.]

[FOD: PULL!]

*****

I finished the 180 aborts and got the call from Jo-Jo to recover, Shortly after that, Jo-Jo called that he was engine-out and demonstrating the TG-7A as a glider with the prop stopped.

I pushed to the airport frequency and called downwind, base, and final through left traffic to Runway 9. Most of the other performers were still airborne out near the waterfront, so I had the airport to myself. I set up carefully and held the airspeed as precisely as I could. I didn’t have to land in front of everybody, but there was still the pressure of yard-sale-ing the aircraft with an awful landing and closing the airport just when a dozen or so aircraft were returning to land.

I put her down, then heard Jo-Jo on the radio, both praising my landing and making sure that I would be clearing the runway for him.

[Landing audio.]

We shut down and debriefed. We had stuff to discuss, but I didn’t hit anybody, I didn’t yard-sale the aircraft on landing, and we looked pretty good.

*****

John showed up that evening with the third ship. We flew a practice the next morning with John assuming his role as 2 and me moving back to 3 as originally planned. The wind had really come up by then. I whacked my head on the canopy a couple of times in the big bumps, but managed to stay in formation reasonably well.

We ended up not flying the demo that day. The wind was gusting to 25 knots. It was right down the runway, but the trouble wasn’t taking off. It was taxiing to the end with the wind at our tails. If the wind gets under the tail and lifts it up, you can end up hitting the prop on the pavement. Prop strikes are considered bad, especially when you’re the new guy.

But the debrief from the practice flight was worth the jostling around and any hairy eyeball that we might have gotten for not flying the demo. Jo-Jo and John talked a little beforehand and then I joined them. As 3, I went first. I evaluated myself as best I could and ended with the phrase that the Blue Angels use in their debriefs. “I’ll fix my safeties and I’m glad to be here.”

There was just enough silence to be awkward and then John and Jo-Jo looked at each other and smiled. Then I got the pounding on the back and a team hug.

“Great job, Dogbag!”

No more getting called “4” or talk of flying a missing man. I was by no means a formation ace. In fact, I flew at the ragged edge of my abilities that day, working up a sweat just trying to stay welded to Lead’s wing. But this was the first indication that my best effort might be good enough to hang with the airshow bros.

Later in the day, the wind died down enough to get airborne and we set out for home. We climbed up into the rarified air at 11,500 feet and caught a slight tailwind to push us home. Lots of turbulence down low means movement in the atmosphere that tends to scrub the particulate matter out of the sky. It’s cobalt blue up there and the yellow TG-7As look amazing against that sky above and Saginaw Bay below.

We switched lead a few times and flew echelon, trail, and whatever else suited Lead. I even got to fly Lead for a half hour or so, but the thing that resonated was each time I checked in on the radio. I clicked the microphone and said “Tuskegee 3.” It had become shorthand for a lot of things.

“I’m where I’m supposed to be. I’m doing what the team expects me to do. I’m flying to a high standard. I’ll fix my safeties and I’m glad to be here.”

I might have different flight callsigns or numbers as I continue to fly but, if anyone ever sticks a mic in front of me in the exhibit hall at ICAS, I’ll say “Tuskegee 3.”

Closer to Detroit, we did some tail chasing that rapidly disintegrated into BFM with yellow longwings all over the sky.

*****

A few weeks later, Jo-Jo called again. He had a line on the show at Scott AFB in Belleville, Illinois just across the Mississippi from St. Louis. He had assured the show that we were warbirds and the show wanted us. What’s more, they wanted the museum’s Tuskegee-flown T-6G, a 5,600-lb WWII advanced trainer.

The week before the Scott show, Jo-Jo staged one of the TG-7As near his home near Chicago, which left two aircraft at Detroit. The Thursday before the show, John Harte and I launched at sunrise to fly those two the nearly 400 nm to Scott. I flew on John’s wing and did my best to stay in close formation.

We flew for seven hours, not including fuel and bio stops. We flew into headwinds of between 12 and 20 knots. Not much for most aircraft, but we were flying TG-7As, which cruise at around 95 mph or about 83 knots. At a couple of points when I was in route or flying lead, I could see westbound cars on the ground moving faster than we were.

We landed at Fort Wayne (KFWA), Edgar County (KPRG), and Greenville (KGRE) along the way. The skies were low and ragged all the way to Fort Wayne and for an hour west of there before they finally came up and the sun peeked out from time to time. After the first few hours, some elements of formation that were a chore before became valuable. With nothing else to do, I flew closer than usual, working on very precise stationkeeping. Just to have something to do. I asked to switch sides a few times to relieve the pressure on my neck from looking right or left. John gave me the lead a few times and I moved him around with the hand signals that I was beginning to work on.

The stop at Greenville was probably the most memorable. John told me to fly lead for the takeoff and a low pass. I took off, then led the formation around in left traffic. Greenville is a non-towered airport and I called out our position around the pattern. On the way back in for the pass, I keyed the mic. “Greenville traffic, wake up the boys and girls and the ice-cream lickers, Tuskegee Flight is final Runway 36, low pass, Greenville.”

*****

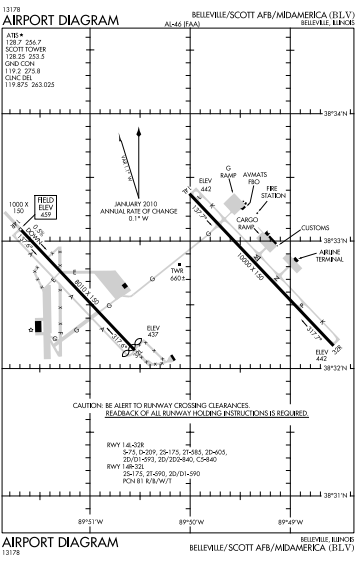

Scott AFB is the southwestern half of a complex that includes MidAmerica Airport. The civilian side on the northeast has Runway 14L/32R, which is 10,000 feet long and 150 feet wide. The base has Runway 14R/32L, which is 8,010 feet long and 150 feet wide. The two sides are connected by more than a mile of Taxiway G, which runs through the woods between the two sides and next to the control tower.

On the way in, the tower kept us near the top of its Class D airspace and then cleared us to land on the civilian side. The museum’s Piper Lance arrived shortly after we did, carrying some of the paperwork necessary to get us onto the base. Shortly, we taxied over to the base – the “mil” side – and tied down the TG-7As.

John returned to Detroit in the Lance, leaving me to button up the aircraft and represent the team until Jo-Jo and the others arrived the next day. I got the rental car, found the housing, picked out the second-best bedroom in the suite, and tried to sleep.

*****

Mike “Kahuna” Stewart of Team Aerodynamix (formerly known as Team RV) once told me that you train so that you can safely fly your airshow demo while performing at 80% of your physical and mental capacity.

Airshows can be rough environments. Sometimes you fly a long way to get there. It’s strange airspace. It can be different airspace every weekend. You sleep in a strange bed in a strange hotel room. Even when you do get to sleep, you usually have to be up and to a briefing between 8:30 and 10:00 a.m. the next day. And, if you don’t brief, you don’t fly.

Getting places takes twice as long as it would if you knew the territory, so you’re always rushing around to get someplace and, if you’re not late, you’re way early and you sit around waiting. Getting resources is the same way. The gas jockey is probably working his butt off to be helpful, but he’s never around when you’re ready to gas up the aircraft. If you’re like many airshow performers, you’re flying with minimal gas to allow maximum performance or to make the weight and balance work with your load of smoke oil. So you have to do that lonely wait for the gas truck after every flight.

If there’s any trouble with the aircraft at a show site a long way from home, you have to figure out how to get it maintained and there might not be an easy way to do that. Especially on a military base where the military maintainers understandably won’t touch your aircraft and where it can be difficult to get a civilian A&P onto a secure ramp – and that’s if you can get him or her through the crowd and the logistical hell of airshow ingress and egress. Contrary to popular belief, there’s usually no magic performer-only ingress and egress to the show site so the performers can lounge around in the air conditioning at the hotel until show time or to get stuff to the performers if they need it. Performers simply tend to get there earlier than you do and leave later than you do.

It’s usually hot. Sometimes, it’s 95F or hotter with the haze of saturated, humid air. And you’re usually wearing Nomex pajamas for at least part of the show. You’ll probably have a hangar to stand around in, but it probably won’t be air conditioned and you’ll be exposed to a higher-than-optimal heat index the whole time you’re on or near the ramp. You can get exhausted just standing around. There’s usually plenty of water and other fluids on the flight line, but they sometimes run out.

And that’s to say nothing of the heat in the cockpit when you close the canopy and get ready to fly. If it’s 95F and the sun is out, sure enough it’s going to be 120F or better the moment you close the canopy. Have you ever sweat so much that you’ve ended up with salt stains on your flight suit? It can happen at an airshow.

Taking a leak isn’t just taking a leak. It’s checking the color of your urine to be sure that you’re drinking enough water. If it’s not pretty close to clear, or if it’s been more than about an hour since the last time you went, you’re not drinking enough.

If you have time to lay down and try to get some rest, there’s usually no place to do it other than on a hangar floor with people tripping over you. And, with a demo coming up in a few hours, I don’t know how anyone could actually sleep.

And you have to be looking out for your teammates, too. Eyeballing their aircraft when you walk by to make sure that somebody with a golf cart hasn’t bent the tail. Watching your teammates themselves for signs of dehydration, heat exhaustion, or heatstroke.

These are not optimal conditions under which to do things that require peak human performance. Like Kahuna says, your job is to make your physical and mental abilities so that 80% is more than enough to fly the demo safely. That’s a tall order. But airshow pilots have to do it.

*****

I went to the briefing on Friday, but the same weather that caused John and me to fly over a day early kept Jo-Jo and the T-6 from making it in until late in the day, after the practice show had occurred. I met them as they arrived and handed out the rental car keys like any good advance pilot. Jo-Jo had a chance to take the wing commander up in a TG-7A, but the day was too close to being over to fly a full practice.

For this show, Jo-Jo would fly lead, I’d fly 3, and Andy “Pigeon” Meyer and Mark “Frenchie” French would alternate flying 2. Bill “Shep” Shepherd flew the T-6.

Shep is a warbird pilot who’s based in Canada. In addition to flying the museum’s T-6, he flies Harvards (the Canadian equivalent of the T-6), P-51 Mustangs, and other warbirds for organizations around the US and Canada. Shep is crazy-respected in the airshow community. I get smarter every time I’m in a room with him. He’s not only a great pilot, he’s a mentor and teacher.

Like before, we needed to be able to say with straight faces that we had flown the demo within the last 15 days. We didn’t get to fly it on the practice day, so we had to get that done before the show on Saturday. The brief started at 0830L and the show started at 1100L, which meant that we needed to get the practice done before the briefing.

We made plans to fly a practice at first light and then headed to our quarters. I didn’t sleep very well. A strange bed in a strange place with a rayon-polyester comforter that kept sliding off one side or the other. And, of course, the constant thought of the show coming the next day.

*****

I met Shep in the parking lot at 0530L and drove him to the flight line, where we met the rest of the bros.

Our demo for the Scott show would be the same as for Rogers City, except that Shep would fly passes in the T-6 first while we orbited behind the crowd, then we’d fly our demo, then Shep would come in at the speed of stink above Lead and 2 as they landed engine-out.

We started up and taxied out to the runway. There’s something about taxiing out as a flight that I’ll never get over. You’re out there to do something together. You’re expected to pull your weight and you expect the others to pull theirs.

And this was the first time that I had taxied out with a two-and-a-half-ton T-6 right behind me as 4. I could hear the T-6 doing its run-up despite being in my own aircraft and wearing a noise-canceling headset.

We flew the demo, then taxied back, shut down, and headed for the briefing.

The briefing for the Scott show was the opposite of the Rogers City briefing. The room was packed with everyone from Greg Colyer to Herb Baker to Thunderbird 7.

It’s not that Scott is different from Rogers City in most ways that matter fundamentally. The aircraft doesn’t care that it’s flying 400 nm away from the last show site. The laws of aerodynamics are the same. But Scott is a much bigger show. Bigger, in fact, than many of the other shows that I’ve attended as media. The huge crowd line out there on the field says that in spades. I glanced at it briefly during the practice flight. The line of hangars and the blocked-off roads around the base say it, too.

And this briefing has the flavor of the room there at the ICAS convention in Las Vegas. A place where many of my heroes are walking around with coffee, waiting for the briefing to start. The difference this time, of course, is that I’m not just a poser. I’m a poser who’s actually going to fly.

I didn’t record any audio at the Scott show. I was too focused on the performance. On not screwing the pooch. But I recorded the Indianapolis Airshow’s briefing in 2009, which was conducted by Ralph Royce, the same air boss who handled the Scott show. Ralph’s briefings are notably similar show after show, which is an indication of how long he’s been doing this and how well-refined he’s made the process. Ralph is also an intimidating figure. He’s an accomplished pilot and has been bossing shows since Wilbur and Orville were just starting out. He has a no-nonsense delivery in the brief and he’s the same way on the radio during the show. Ralph’s presence and voice made the whole thing even more real.

To give you an idea, here’s a montage of what it sounds like in a Ralph Royce briefing.

[Royce montage.]

I took great notes and paid really close attention. Emergency procedures. Divert procedures. Frequencies. If something went wrong, I didn’t want to be the guy wandering around where he wasn’t supposed to be or in the way of other ops.

During the brief, Lt Col Jason “Buzzer” Koltes, Thunderbird 7, gave us crap about not flying real gliders. We, of course, responded that the Air Force had put the motors in them and that we were doing the best that we could with them. All in good fun. But it’s also non-trivial that the featured performers at least thought enough of us to make fun of us.

After the brief let out, we headed back out to the aircraft to make sure that all was ready to fly the demo. I did another complete preflight, then pulled the mains out of the grass and up onto the concrete.

Once everyone else was ready, we gathered on the ramp and walked through the demo a few times, but, after that, there was nothing to do but wait the hour or so until it was time to fly. I headed over to my bird and tried to clear my head and focus on the performance. Standing there on the performer ramp with the crowd area filling up and watching the weather, you realize that you’re doing a very different thing from what you’ve ever done before.

*****

You’ve heard a lot about personal minima. You probably have them. Wind, ceilings, and other parameters outside of which you decide in advance that you won’t fly. They’re pretty easy things to stick to when you’re Joe Private Pilot deciding whether to go get lunch at the next airport over. I’m the same way. I’ve been very fortunate through most of my flying career. I’ve never had to fly. I’ve never had to be somewhere at any particular time. “Get-there-itis” and similar accident causes have been utterly unable to reach me.

Until now. If you think that your aeronautical decision-making is solid and immune to pressure, you need to do a little thought experiment with me. It’s Saturday. You’re standing next to your aircraft. Your preflight inspection is complete. The sky is overcast at 1,500 and it’s coming down. The wind is at 15 knots directly across the runway. The left mag on your aircraft has been running a little low after startup, but you’ve leaned it out on runup each time and it ultimately checks out within parameters. You didn’t sleep that well last night. You’re a little dehydrated, but yet you need to hit a bathroom and both the water and the porta-potty are too far away to allow you to get there and back in time. It’s a strange airfield. You’ve only flown here once before. That was yesterday and the traffic is going the other way today.

Would you fly? Depends on your minima. If you knew that you could do it, you’d do it. You might even have done it before. But there’s a whole pile of factors there and each of them could be a link in an accident chain. Would you fly?

If you think that you’d stand down and just not fly, let’s add some stuff. There are two other aircraft nearby with two other guys standing next to them just like you are. They’re going to fly. They expect you to fly. They’re depending on you to fly. You’re 3, after all, right?

Let’s add more. Just a few hundred yards away is a crowd line. There are thousands of people lined up along it. They expect to see an airshow. The kid that you once were is in that crowd and this could be the day on which he or she sees a yellow longwing doing 180 aborts and decides to become an astronaut. The kid expects you to fly.

Somewhere in that crowd is the airshow chair. He or she expects you to fly. And the airshow organizer might short-pay the team or speak ill of the team for failure to put up the demo that you promised.

Look around the ramp. Your heroes are walking around, preflighting, talking, and watching you. The people who you most want to be like. The people whose respect you want so bad that it makes a hurty place in your stomach when you think about it. And they’ll notice if you don’t fly. And it’ll come up tomorrow morning at the Sunday briefing with all of them in the room.

Are you going to fly or not? Don’t even try to answer. The point is that these circumstances will affect you. Your risk calculus will change. You cannot be in this situation and fail to have it affect you.

Three acts before our slot, we strapped in and started up. Comm checks among the three TG-7As were crisp. Shep came on our frequency and checked in in the T6 from across the ramp. We pushed to the airboss frequency and taxied out on to Taxiway G. The airboss cleared us to taxi and hold short of Taxiway A, short of Runway 14R.

Holding short with two company aircraft in front and a T-6 behind is an interesting place to see an airshow. That is, if you’re not utterly preoccupied with not screwing the pooch. Aerobatic passes going on just a hundred feet or so in front of you. It occurs to you how beautiful some of this stuff is from so close to the action.

But reverie doesn’t last long out in the box. There’s an airboss call: “Gear up! Gear up! Gear up! Go around!”

Another performer had gotten distracted and was about to land with his gear still tucked up in the wells. I looked to my left and saw the aircraft low and dirty and with the gear now coming down. As though I needed a reminder of how easy it is for even seasoned pros to get sideways and miss essential checklist items. Wow. And Ralph called that out in the brief the next morning. Credit Ralph with the save, so I guess he can say what he wants.

My take-away? If a seasoned airshow vet like that guy can make a stupid mistake like that, how many ways might I screw the pooch? Best just not to screw up. Best to focus. There’s no room for fanboys or posers out here. Only pros. Do I sound repetitive with this? It’s because that’s a genuine aspect of the experience and there are reminders of it every day at every show.

Ralph cleared us out onto 14R at the intersection and we took off in sequence on the remaining 2,500 feet of that runway, making a right turn to get to our orbit point. I pulled up into loose trail and Jo-Jo took up a circling hold about two miles south of the field. Shep circled a mile southeast.

Soon enough, Ralph called Shep in for his demo and the three TG-7As moved to a mile out, circling behind the crowd at 1,000 AGL. I tried to keep the other two guys on the horizon to keep the same altitude.

Soon enough, Shep called his last pass and Jo-Jo turned inbound. I poured the coals to it and brought my bird around to get to the far right. Jo-Jo figured out that he was about to leave me behind and he throttled back, giving me the chance to catch up and be 500 feet abeam Pigeon as we crossed the crowd line 1,000 feet below.

Again, the aircraft and the laws of physics don’t care that there are thousands of people down there. But it’s a really, really different sight picture from the practice and from Rogers City. Jo-Jo nosed over and headed into the box proper. I had the chance to look over the nose and see not only the crowd but the expanse of the base and even the Thunderbirds’ F-16s lined up over at show left.

Jo-Jo called the break and all three aircraft went wings-up. I matched Pigeon in the break and we leveled just outside the 500-foot line before Pigeon rolled right to follow Jo-Jo around the corner.

The racetrack and the figure-eight went great. I figured out when to roll for the turns and had the spacing pretty well dialed in by the second trip around. I also got past a couple of pucker-inducing moments in the turns toward the crowd. I sure as hell didn’t want to break the 500-foot line or go beyond 60 degrees of bank, but I wanted to roll out as close to the 500-foot line as possible to keep the aircraft as visible to the crowd as I could.