This is a two-part presentation, but I wanted to keep everything in one place. Accordingly, I’ll put links to both audio parts here as they’re released.

Part 1:

Part 2:

Because Glider: Being an Account of One Man’s Path to the CFI Certificate by Way of Uncle Ernie’s Holiday Camp, a Couch at a Radio Station, &c.

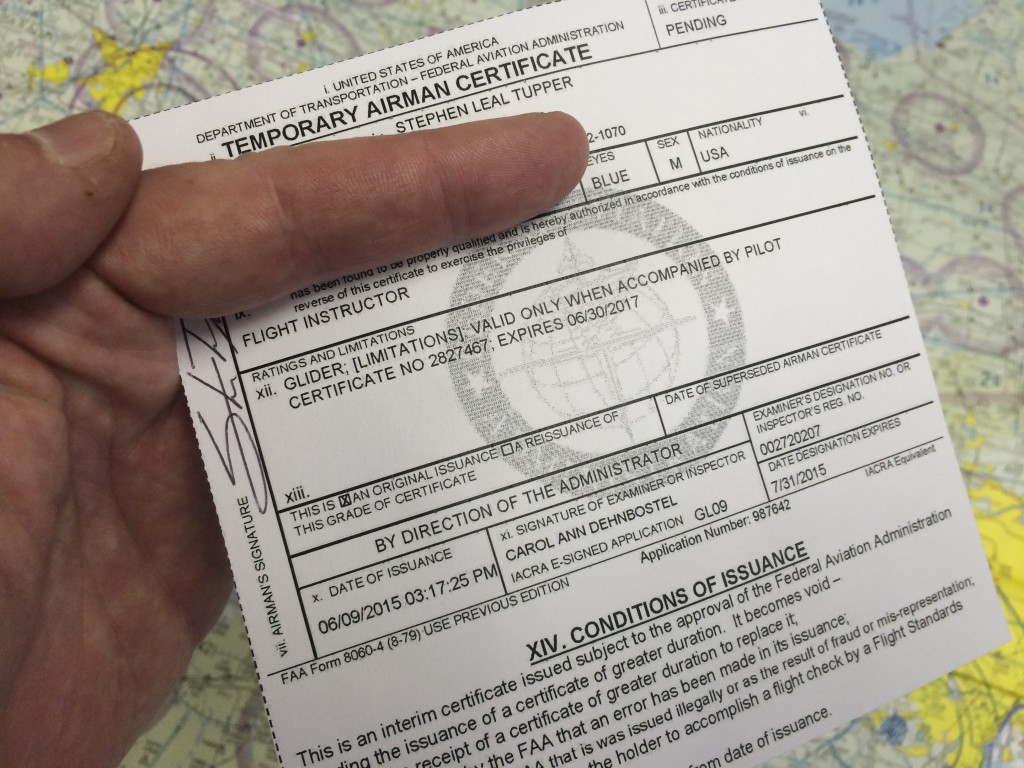

If you follow me anywhere on social media, you’ll know that I recently completed the Herculean effort of becoming a certified flight instructor (or “CFI”) in the glider category.

I first started flying gliders in 2012 when my friend, and later instructor, John Harte, invited me to go fly a motorglider after a haircut that I had scheduled in Detroit one Saturday. By the second time we flew, I was training for the rating. Four months later, I was a commercial glider pilot and, six months later, I flew my first airshows as a performer in the same aircraft. Since then I’ve logged more than 200 hours in motorgliders, more than half of that in formation.

Through the kind efforts of Mark Grant, Chris Felton, and others in the Civil Air Patrol, I even added an aerotow endorsement so that I could fly gliders that had no onboard powerplants. I earned that one after about 20 tows, most of them conducted in Owosso, Michigan in single-digit Fahrenheit temperatures where you had to close the canopy and hold your breath until you had airflow through the window on takeoff so you wouldn’t completely frost the inside of the canopy. If you earn an aerotow endorsement in Michigan in the winter, you have well and truly worked for that endorsement.

And then, like the urge of Ishmael to get to sea, I began to feel the urge to do the next big thing. Certainly, there are plenty of challenges that could have been that next big thing. I really ought to add both single- and multi-engine airplanes to my commercial certificate.

But a number of things pushed me to go for the CFI. I’m very broad in aviation, but not very deep. Until I started flying gliders, I could fly a lot of stuff, but only with private privileges. I did my glider checkride at the commercial level simply because the practical test standards are about the same for private vs. commercial and the only other requirements are the knowledge test and a more comprehensive oral during the checkride. (Written test and comprehensive oral? Oh, please don’t throw me in that briar patch!) So the idea of taking a single category of flying all the way to CFI appealed to me.

I have a son who was getting close to turning 14 at the time. His name is Nicholas, but most of you know him by his callsign, “FOD.” He has about 30 hours bumming around in the TG-7A with me, most of it sitting there in the instructor seat while I fly. 14 is an important age for someone who flies gliders because that’s the age at which you can solo. And it doesn’t matter that the aircraft has an engine and a propeller. If it’s certified in the glider category, you can solo it at 14. I decided that it was not enough to just fly around with him or teach him without having the CFI in my pocket. I wanted to take him to a real CFI for the solo and the checkride.

Lastly, I had always thought that instructing would be fun and that I’d become a much better pilot if I did it. During the DC-3 rating, I had the chance to sit in the back and watch somebody else fly under circumstance where I could just watch and think about flying. That was one of the most productive experiences I’ve ever had in flight training. I couldn’t help but think that being able to really observe and critique would make me a much better pilot.

So, last spring, I decided to go for the instructor certificate. This is the story of that journey.

Some quick background. In the United States, you get one or more airman “certificates.” (They’re not called “licenses,” by the way. Quit calling them that.) A certificate designates you as a particular thing. You can have a private or commercial or airline transport pilot certificate. By the way, when you become a commercial pilot, you give up your private pilot certificate and you get a commercial pilot certificate. If there are categories or ratings on your certificate other than the ones for which you qualified as a higher-level pilot, your commercial certificate states that your privileges in those categories are limited to the lower level. You can also have a ground instructor certificate and a flight instructor certificate.

For your pilot certificate (private, commercial, or ATP), you get category ratings. A private certificate is always initially issued in some category, usually airplane-single-engine-land or glider. Although you can go on to add an instrument rating and/or type ratings to your certificate, let’s leave it for the moment at the category level.

There are also endorsements. Endorsements don’t go on your certificate and there’s ordinarily no record of them with the FAA. They go in your logbook and nobody gets to see them unless you show them off or the FAA or NTSB asks to see them. You’re probably familiar with endorsements for high-performance airplanes, complex airplanes, or tailwheel airplanes. There are endorsements for gliders, too.

In order to act as pilot in command of a glider, you must hold one of three launch endorsements, each of which pertains to the method of launch. The endorsements are aero-tow (being dragged up behind an airplane or other powered aircraft), ground-launch (being dragged up by a winch, car, or other device that stays on the ground), and self-launch (getting up using a power source that you carry in the glider with you, such as an engine). To act as PIC of a glider, you must, among other things, be endorsed for the launch method used. As a certificate candidate in gliders you take your checkride using a particular launch method (although I suppose you could use all three if you wanted to have a really cool checkride). If you get an endorsement for an additional launch method later, there’s no FAA checkride. You just go do whatever you’re endorsed to do. That means that, as the ink from a new launch endorsement is drying in your logbook, you can – depending on your pilot certificate – go fly in that launch method for fun as a private pilot, fly for money as a commercial pilot, or give instruction as an instructor.

That’s a lot of information. But the twists and turns of this story make that information useful.

In many ways, this story a lot like the other stories that you’ve heard me tell. But it’s also different in several important ways. Particularly, it was the toughest rating I’ve ever gotten, not because of the learning or the flying but because of the obstacles that I had to confront in the journey.

Have you ever seen the musical Tommy? Tommy, the protagonist, needs something – a cure for what makes him blind, deaf, and dumb – and he’s taken to a succession of characters who are supposed to help him, or at least not make him any worse. But each instance ends badly in one way or another. Uncle Ernie, Cousin Kevin, the Gypsy, and others. Trying to get an initial CFI checkride in the glider category was a lot like being Tommy. I’m not saying that I was molested or that drugs were involved. And I’m not necessarily equating any particular person with any of those characters. But things happened that were very nearly as unpleasant as Tommy’s experience.

The Terrazzo Falcon

I mostly fly the TG-7A Terrazzo Falcon. It’s a self-launching touring motorglider made up of the nose, cowling and engine installation from the Piper Tomahawk, wings from the Schweizer SGS 1-36 Sprite with including extensions to bring it from the Sprite’s 46.2 feet to 59.5 feet, and the tail from the Schweizer SGS 2-32. The US Air Force Academy operated the model between 1982 and 2002. The Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum now operates four of them, all surplused from the academy at one time or another.

It looks like an airplane from the firewall forward (mainly because those parts come from an actual airplane) and the rest of the aircraft deserves the affectionate name that we’ve given to it and that was featured in Episode 6.08 of The Aviators: The Franken-Glider. The fact that it has an engine and flies just fine over long distances under engine power just like an airplane figures heavily in this story. But we’ll get to that.

I started by asking John to hop back in the aircraft with me and fly right seat. You’ll recall that the TG-7A has two seats side-by-side. It’s an Air Force trainer and Air Force doctrine calls for the pilot to have the stick in the right hand and power in the left. Just like the Tomahawk, there’s only one throttle and it’s in the middle. That settles the seating issue because, if the power has to be in the left hand, the PIC has to sit on the right side. Actually, the TG-7A flies best with a single pilot on the right side because its single fuel tank is in the left wing.

After 200 hours in the right seat, I was pretty sure that I could fly from the left side, but I’m cautious and wanted John to be there for the first few exploratory flights. He wrung me out with stalls, 180 aborts, no-spoiler landings, and all manner of equipment malfunctions and pronounced me ready to start getting good in the left seat.

The Plan

I set up a grand plan. I’d begin flying with people who were rated pilots but who had little or no experience in gliders or motorgliders. I’d also begin flying with FOD in the right seat and gradually letting him do more of the flying as I got comfortable flying from the left seat – and/or saving us if he screwed up anything. And I’d fly with John to check in and make sure that I was making progress.

At the same time, I’d work on the two FAA knowledge tests that I’d have to pass: Fundamentals of Instructing (or “FOI”) and the Flight Instructor – Glider (“FIG”) exams.

With this general idea in mind, I set out on the path.

I started by calling up friends like Norm Malek and stuffing them into the right seat. Norm is an instrument-rated private pilot with a few hundred hours in airplanes. He did his first solo in the same month that I did mine back in 2001, just a few airports over. Norm has no glider time.

We strapped in and took off and I gave Norm the controls just after rotation, then coached him about airspeeds and control inputs. We flew up to Romeo, about 20 miles north, to find some crosswinds and do a 180 abort or two. On the way back to Detroit, I pulled his throttle to idle, had him pitch for best glide speed, and challenged him to make it all the way to the airport. Norm had his doubts about making it that far, but marveled as we coasted five miles, burning off only 1,500 feet or so of our initial 2,500 AGL altitude on the way and arriving in the pattern right at pattern altitude.

That was fun. Helping someone discover new things in aviation. I was really enjoying this pseudo-instructor thing.

And it only got better when I put FOD in the right seat. With one pillow under him and another behind, he can reach the pedals just fine and he’s strong enough to be able to apply forces to the stick that are sometimes required when you hit a gust in an aircraft with a 59.5-foot wingspan.

We began with high airwork like steep turns and stalls and I taught him to fly pretty good parabolas (pushing over the top so you get light in your seat or even float stuff in the cabin). Flying parabolas is a good idea both because it builds finesse and because the push that you have to do if you lose the engine on takeoff is very much akin to the push for a parabola. The push feels weird to the uninitiated, so I want my students “initiated.” I don’t want one to go easy on the push because of the uncomfortable sensation. If one of my students ever has an engine-failure event like that, there’ll be a lot more to be uncomfortable about than being light in the seat and I want him or her focused on the things that are more than just uncomfortable.

And, in addition to those reasons, it’s a lot of fun. Even when he was just 10 years old and I was taking him on his first few flights, he repeatedly said “that never gets old.” I’ve got video footage of one of those parabolas where all of the dirt on the floor rose up in a level plane that passed through the camera’s field of view just before a pen floated up in front of my face. An astronaut career three seconds at a time.

We also spent a lot of time in the pattern at Detroit City. I helped more on the landings than I should have, but the TG-7A isn’t as easy to land as the usual ab initio trainers and I was also learning when to intervene and help get the aircraft on the ground – which was a lot. FOD likes to flare high and, although the main gear are very overengineered and beefy, the aircraft is 30 years old and we need to treat it as gently as we can.

On Thanksgiving morning, we got up before sunrise and were in the pattern around 0800L. I noticed a plume of smoke a mile or two northeast of the airport. There was nobody else in the airspace, so I asked the tower if we could go check it out. The tower cleared us and I had FOD fly toward the smoke. Once there, I had him circle the fire at about 1,000 AGL. It was a residence and the place was well and truly burning. Angry orange flames were shooting out of the windows. But no fire trucks.

I called up the tower and asked if the controller wouldn’t mind calling DFD to see if the blaze had been reported. A couple of minutes later, the tower said that it hadn’t been reported, but that, if I gave the location, they’d send a crew. I told FOD to continue circling, talking him through wind correction to keep his turns around the point of the fire while I counted streets north and east of the airport and relayed the information to the tower.

I’m a rated Mission Pilot with the Civil Air Patrol, so this comes at least as naturally to me as it does to any civilian pilot. In fact, this was easier than most CAP air-to-ground spotting because all I had to do was get within a couple of streets and the fire department would be able to see the smoke and home in even if I was off. But it was a really cool moment to be able to share with FOD. 10 or 15 minutes later, we could see the fire trucks rolling up. As we returned to the pattern, I told him – truthfully – that he had flown a real reconnaissance mission and assisted in a real emergency response. When you’re 12 years old, that’s a pretty cool thing. It’s not bad when you’re in your 40s, either.

Spins

Among the requirements to become a CFI is the requirement that you receive training in spin recognition and recovery and receive a logbook endorsement evidencing that training. This is the only training in spin recovery that’s required anywhere in the regulations. Spins used to be required for the private pilot certificate, but that phased out long before I began flight training in 2001. The instrument rating requires recovery from unusual attitudes, both full and partial panel – usually a nose-low attitude with airspeed increasing or a nose-high attitude with airspeed decreasing. There’s usually a bank included somewhere in there as well. The skills required are instrument interpretation and then the ability recognize the proper response. If nose-low, pull power and level the wings before pulling. If nose-high, add power, push the nose over first, then roll level.

That’s all good. But you don’t have to actually recover from spins until you go for the CFI. That’s because it’s a pretty good bet that some student, sometime, is going to spin you. I don’t know any instructor who’s been teaching more than a couple of years who hasn’t had a student get a big wing drop and the beginning of autorotation.

You’ll recall from your private pilot training or ground school that a spin is what can happen when you stall an aircraft uncoordinated. One wing or the other drops and the aircraft begins a rotation in the direction of the dropped wing. The high wing has more airflow on account of being on the outside of the turn and thus develops a little more lift and down you go.

Many pilots will react quite naturally to a spin by reacting to the stimuli they see out the window.

- Lots of chlorophyll in the window and the houses getting bigger: Pull.

- Rotation (often to the left in American piston singles): Opposite aileron.

Bad in both cases. Pulling increases or maintains the angle of attack that caused you to stall in the first place and opposite aileron is actually a pro-spin input (think about it in a spin to the left – down aileron on the left wing increases the angle of attack and deepens the stall on that wing and up aileron on the right wing decreases the angle of attack and makes it a little less stalled, thereby accelerating the autorotation).

As an instructor, you need to be able to recognize what’s going on and either prevent the spin or recover from the spin after it develops.

The spin training wasn’t a big deal for me. As an aerobatic pilot, I’m trained to not just recover from a spin but to perform a specified amount of rotation (at my admittedly basic level, either one turn or one and a half turns) and come out on a specified heading. You get gigged points if you come out off-heading. And, in competition, it’s usually necessary to recover pointing straight down and give it a couple of potatoes of full throttle before pulling out – the better to have a lot of smash for your next maneuver, recently a half Cuban or a pull-pull-pull humpty.

I could, and did, get Don Weaver to sign off a spin endorsement for me based on the training and competition that I’ve done with him in the other seat of the Pitts.

But, if you read the regs closely, I think you’ll see that the spin endorsement should probably be done in an airplane for the CFI airplane and in a glider for a CGI glider. I could argue that an endorsement in an airplane ought to count for a glider CFI (and many authorities say that it does), but I didn’t want to have to have the argument at a checkride.

So I went to Sandhill Soaring in August to get up with John Harte in the Grob 103. The Grob is aerobatic certified and is the ship most often used at Sandhill to train in spins and unusual attitude recoveries.

The training was mostly uneventful. In fact, without adding aft weight, it’s really hard to get the Grob to do anything more than chuff into about a quarter-turn incipient spin before the nose comes down and autorotation ceases. This with the stick in your belly and the rudder all the way to the floor. We managed to do things that I think I can say with a straight face had flavors of autorotation, but nowhere near what a Pitts or a Super Decathlon will do, especially if you let the spin wind up and even flatten it. Still, it was fun getting up there and exploring more of the envelope of the aircraft.

And I learned this: Stalls and spins in every glider in which I’ve flown are amazingly docile. There’s a buffet, you let off on the stick just a half inch or so, and you’re out. It’s actually hard for the uninitiated to tell that the aircraft is stalled. In fact, the minimum-sink speed in most gliders is just a few knots above the stall speed anyway. Until you get really good at thermalling and just feeling your angle of attack, you stall the aircraft all the time. It’s so gentle that you sometimes have to remind yourself that you’re stalled. And the only consequence is that you’re not climbing very well in that thermal.

If you’re an airplane pilot and you don’t like stalls, you have yet another good excuse to go to your local glider operation and get up for a stall series. Seeing stalls happen in slow motion with docile reactions will do a lot to build your confidence and see what stalls are really all about.

FOI Folderal

All during this time, I was working on the FAA knowledge tests and preparing for the non-flying part of the rating.

There are two different knowledge tests for the rating. The Fundamentals of Instruction (or “FOI”) test covers the instruction and learning process and the Knowledge Test covers the specifics of regulations, technique, and the other stuff that actually matters to glider flying.

The squishy sciences like sociology and psychology have it tough. More than most scientific endeavors, they’re only just up from the depths of superstition and quackery. Many practitioners and investigators in these areas are doing their level best, but they have to contend with institutional review boards (“IRBs”), fussy test subjects, and very limited funding. The result is that there’s comparatively little reliable science in these areas.

Witness in particular a recent piece in the journal Science in which the authors tried to replicate 100 experimental and correlational studies published in three respected psychology journals. The study showed that, where 97% of the original studies had positive results, only 36% of the replications showed positive results.

This is okay. Science is self-correcting. The evidence will eventually point to the right answer. But, in the meantime, the FAA is going to want to evaluate potential flight instructors’ understanding of instructional methods. And it’s going to want to do that before the science is settled. And it’s going to have to come up with an FOI examination that will be out there for five or 10 years without changes, even if the science moves on in the meantime.

So that’s what you get, dear listener. The FAA drives a stake into the ground at a point in time and then it contracts a bunch of angry and frustrated English majors to write up a test. So you get a number of things.

You get bad science. For example, left-brain/right-brain dichotomies that have no basis in fact. Meyers-Briggs personality typing that is demonstrably wrong in its conception and used poorly.

You also get stilted vocabulary exercises. The psychomotor domain (itself an arbitrarily invented division of human attention and skill) is divided into Perception, Set, Guided Response, Mechanism, Complex Overt Response, Adaption, and Origination, each of which has a definition and a place in a hierarchy. Even if this stuff was helpful – and it’s really not – it isn’t used in flight instruction and it isn’t even used on the checkride by any FIE or DPE I’ve ever met or heard of. Or if it is used, it’s solely at the rote level of learning (and not at the Understanding, Application, or Correlation levels – yet another hierarchy that I learned by – um – rote). It’s all a waste of time and exists solely so that the FAA can feel as though it cares about the process of flight instruction.

I’m not saying that the FAA couldn’t write a knowledge test that focuses your learning on – and tests your knowledge about – worthwhile stuff. Identifying stress and anxiety in students. Identifying learning plateaus. The CFI’s responsibilities and endorsements and recordkeeping. And there’s some of that in the FOI. But not enough to justify a separate test or another $140 and a pile of time on the path to the CFI certificate.

The Flight Instructor – Glider Knowledge Test

On the other hand, the actual Flight Instructor – Glider test was pretty good. One thing I can tell you is that you have to actually study for it. For all of the airplane ratings, you can use study software that runs you through the actual FAA questions such that you can spend a few hours with the software, take the knowledge test, and score a 90+% without even really knowing the subject matter.

The most mercenary of the companies that offer this software is Sheppard Air. The Sheppard system suggests that you start out by running through all of the questions in a mode that shows you only the question and the answer. The only thing that you’re learning is to recognize that correct answer. You don’t even read the question other than to identify which question it is so that you can identify the right answer. After you’ve done that, you go through all of the questions showing all of the answers but, by that time, you can recognize the right answer immediately anyway on all except for a few questions. At that point, you go to your local testing center and sit for the test.

In no way will Sheppard make you ready for a CFI oral or even give you the minimum information you need in order to be a semi-knowledgeable airman. But it’ll get you through the FAA knowledge test with a 90+% with only a few hours of prep. I know this because, during the doldrums between efforts to get my CFI ride, I became an advanced ground instructor and instrument ground instructor with a total time investment of less than eight hours, including the drive to the testing center.

Look, we all know that walking into your FAA checkride oral with rest reports that say 95% is a great way to start out your checkride on the right foot. In fact, even knowing that I’m going to get hate mail for saying this, I recommend going through a Sheppard-like process for your FAA knowledge test. I say this for a few very good reasons.

(1) There’s nothing wrong with starting out your checkride on a good foot. One of the first things that the examiner is going to do is check your paperwork and the knowledge test results are a part of that.

(2) Getting the knowledge test out of the way allows you to focus on the actual stuff that matters. It allows you to spend time with the appropriate FAA handbooks and circulars in a way that allows you to pay attention in an integrative way. You’re not halting every page to fleaspeck and memorize stuff.

(3) It’s not as though you’re actually going to get away with anything. Even if you walk in with a 100% knowledge test score, the examiner is going to figure out in the first 20 minutes or so whether you know anything. Go ask any examiner. Just about every examiner will tell you that they’ve rarely failed anyone on the oral without knowing within the first 20 minutes that it’s just not going to happen that day for that candidate.

That said, being in the glider category makes everything different. For one thing, there’s no Sheppard test prep package for gliders. In fact, I don’t think there’s any available online or computer-based prep for the glider knowledge test. There just isn’t enough demand for it.

I had the benefit of the Shepard test prep for the Advanced Ground Instructor certificate and there are common questions on the airplane and glider tests. Things like reading METARs and charts. But the rest required spending a lot of time with the FAA Glider Flying Handbook. Mostly things that I hadn’t personally experienced, like ground launch operations, identifying thermals, and CG tow attachments.

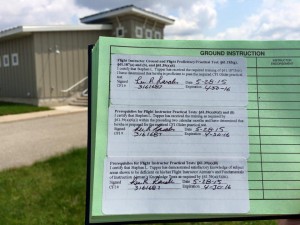

I knocked out the FOI on Easter Sunday 2014.

The summer ensued and my test prep dragged out but I worked during September and most of October 2014 on the FIG, then went in to take the test. I was met in the lobby by a witch, who examined my ID, did the paperwork, and then put me through the test. Yes, a witch. A nice witch. I took the knowledge test on Halloween.

I walked out with an 88%. For reasons stated above, I really like to have something that begins with a “9,” but I presumed that glider examiners are probably used to lower scores because of the unavailability of Shepperd and similar test prep systems.

I called John from the gas station on the way home to tell him about the test results and plot my next move. Halloween fell on a Friday and the plan was to call the FSDO on Monday and tell them that I was ready for the ride. It takes at least a couple of weeks to set up an ab initio CFI ride, so I figured that I could just start studying over the weekend. If they called right away, I could cram hard and get ready in time. Even if they didn’t call right away, knowing that the call could come at any time would be an incentive to study hard and be ready.

As it turned out, I needn’t have worried about the ride happening too soon.

What’s a Glider?

Remember when I said that the engine and other features of the TG-7A would come into play? Here’s where that starts.

Something is that doesn’t love a TG-7A. Or self-launch gliders generally.

This plays heavily in the story of my ride. Almost everywhere I go, somebody wants to tell me that it’s not a glider or that it’s not a real glider (whatever that means). And preconceptions and prejudices like these made this entire process a lot harder than it had to be.

Let’s talk for a moment about what makes an object a glider, as opposed to an airplane, a golf club, or some other object.

A glider is whatever the FAA or other governing agency says is a glider. In the US, an object becomes a glider through certification under Part 21 of the FARs. FAR 21.17 identifies the airworthiness requirements for aircraft and FAR 21.17(b) applies to “gliders, airships, and other nonconventional aircraft.” It then essentially punts the ball to Joint Airworthiness Requirement 22 (or “JAR-22”), which is a standard maintained by the Joint Aviation Authorities Committee. Civil aviation authorities from around the world sit on the committee and they gather in a secret volcano lair somewhere and come up with what an object has to be or do in order to become a glider.

Generally speaking, in the US, if you want to make a glider, you build a thing that complies with JAR-22 and then you apply to the FAA for a type certificate. Schweizer did just that with a TG-7A and the FAA issued type certificate G1NE on March 22, 1983. K & L Soaring of Cayuta, New York, now holds that type certificate.

There is some argument that the certification of the aircraft could have been as a single-engine airplane had Schweizer simply checked a different box. In fact, later derivatives like the SA 2‑37A and SA 2-37B were indeed certified as airplanes. Add to that the fact that modern manufacturers like Pipistrel will take an order for what amounts to the same aircraft and let you decide whether you want it certified as an airplane or a glider. I’m not arguing that the TG-7A doesn’t have airplane-like qualities. But it remains that the FAA certified the TG-7A in the glider category.

As far as the FAA is concerned, the TG-7A is a glider. Full stop. This has very real consequences.

A person who does not possess a glider category rating or a FAR 61.31(d) endorsement cannot legally serve as pilot in command of a TG-7A under any circumstances. How about a 10,000-hour ASEL pilot with a tailwheel endorsement with respect to whom there’s zero doubt that he could take off, maneuver, and land safely and even elegantly? Nope. Without a glider category rating and the proper endorsement, that guy can’t legally operate a TG-7A as PIC.

There’s a sense that pilots who want to fly the TG-7A are getting away with something. They can fly if just like an airplane. And it’s true that such pilots can and do. In fact, I do most of the time. But I had to meet dual and solo experience requirements, take an FAA knowledge test, get through a three-hour oral, and pass an FAA checkride to get my commercial glider certificate. Even at the private level, ASEL pilots have non-trivial hoops through which to jump to earn the privilege. We’re not getting away with anything. We pay the price of admission to the category, just like anybody else.

By the way – and I do have to say this because this is a real misconception – it does not matter whether the engine is running. It’s a glider under all circumstances. The category in which the TG-7A is certified does not change. An ASEL pilot without the right rating and/or endorsements can’t serve as PIC in a TG-7A, even if a glider pilot with a self-launch endorsement starts the engine for him and he keeps the engine running through all phases of operation.

And, believe it or not, the TG-7A gets treated poorly from the ASEL end of things, too. An uninformed inspector at the local FSDO recently told one of my primary students that he couldn’t count TG-7A time toward his ASEL private pilot experience under FAR 61.102 unless the engine was running. Never mind that we did very little engine-off work. The fed’s statement is manifestly untrue. FAR 61.109 requires only “flight time,” of which only a maximum of 22 hours need be in airplanes. The other 18 hours could be in powered lift for all the regulation cares. But you see people – even feds who are supposed to know the difference – drawing distinctions that aren’t there.

The TG-7A is a glider. It is a glider by day. It is a glider by night. It is a glider when the engine is running. It is a glider when the engine is not running. If a TG-7A impacted terrain and shattered into a million tiny pieces, the last shard of aluminum still riveted to the data plate would be . . . a glider.

So let’s talk about expectations and the brush with which people paint the TG-7A and those who would become instructors in the TG-7A or other self-launch gliders.

In saying that the TG-7A is a glider, the FAA unequivocally states that what a TG-7A does is a part of what gliders do. Whatever the TG-7A does within the limits of its type certificate is what a glider does.

I understand that people are used to Schweizer 2-33s and Schleicher ASK 21s and the paradigm of a glider is closely identified with aircraft that look like 2-33s and ASK 21s. Slippery-looking aircraft with long wings and no onboard engines.

But too many people – among them people who should know better – take the paradigm too far by restricting their thoughts about the glider category to those examples. They assume, incorrectly, that a TG-7A must be flown like a 2-33 or an ASK 21 in order to achieve gliderness. Because glider.

That’s wrong. The FAA does not say that the TG-7A is a 2-33 or an ASK 21 or that the TG‑7A must perform like, or be flown like a 2-33 or an ASK 21. Quite the contrary. When the FAA said that the TG-7A is a glider, it said (yea reaffirmed) that the category of gliders, and what gliders do, is broader than the 2-33 or an ASK 21.

A TG-7A doesn’t have to do what other gliders do. Any more than a C-152 needs to cruise at 130 KIAS or have retractable gear to be an airplane. I can take the example even closer to home. The ASK 21s operated by the US Air Force Academy had no CG hooks – only nose hooks. It would be a really dumb idea to do a winch launch of an ASK 21 on the nose hook; so much so that you could say that the ASK 21 is incapable of being launched on a winch. But is an Academy ASK 21 less of a glider because it can only be launched using aerotow? Nope. It’s a glider.

Let’s go all the way in that direction. Nobody expects a 2-33 or an ASK 21 to do what a TG-7A does. Those gliders don’t self-launch and nobody seems to mind. They don’t have carb ice detectors and nobody seems to mind.

The TG-7A is a glider. And, by definition, what a TG-7A does is a part of what gliders do. You don’t have to like it and it can be a major departure from your paradigm of gliders, but you don’t get a vote. If a TG-7A does a thing that’s within its type certificate, that thing is a glider thing and the glider category encompasses it.

The next objection comes from expectations of the pilot. What if I get certified to fly gliders and don’t know anything about what it’s like to fly a 2-33 or an ASK 21?

First off, so what if I do? If I did my checkride in a TG-7A and never flew, or instructed in, any glider other than a TG-7A or another touring motorglider, doing what one does, and teaching what one teaches, in a touring motorglider, how would that be a problem?

You might try to impose a restriction on me, limiting my CFI privileges in gliders to self-launched gliders. Or to the TG-7A specifically. That would be mean-spirited and short-sighted of you. But, actually, that would have been fine at the time. All I ever really wanted was to teach in the TG-7A. But, as we all know, there’s no such available limitation. You get your CFI for the whole category and you can instruct in any launch method in which you have an endorsement.

But what if I get my CFI in a motorglider and then go out and instruct in aerotow? After all, you can instruct in any launch method for which you’re endorsed. In fact, an instructor can give dual in that launch method on the very first flight after he or she is endorsed while the ink is still wet in his or her logbook. Well, what if I do?

The FARs are replete with enough rope for any pilot to hang himself. I haven’t flown PIC in actual IMC in more than three years. I haven’t done any hood work in more than two years. But I shot six approaches and a hold in a simulator last month and I can legally load the Pope, the Dali Lama, and the president of the United States into a C-182 and go fly in low IMC, including a zero-zero takeoff. So can thousands of other pilots.

Legal? Absolutely. Smart? No. But the regulations trust pilots to not do stupid things. If you’re worried about me going up and doing stupid things, you really need to worry about a lot of other perfectly legal things that thousands of other pilots do before giving me grief.

Let’s take it a little further and the issue gets even more plain and stark. Let’s take someone who has only ever flown aero-towed gliders and gets his CFI in aero-towed gliders. The only thing between that guy and instructing in self-launch gliders is a self-launch endorsement. If you’re worried about me, you need to redirect your worry at this guy. All he needs is for someone to pencil-whip him a self-launch endorsement and he adds all of the complexity of an engine and a prop (or a jet engine in at least one case) and all associated systems. But I’ve never heard anyone complain about the possibility of an aerotow guy going out and doing stupid things outside the realm of his training and experience.

Lastly, The Soaring Society of America schizophrenic at best and a pile of haters at worst. Its Twitter feed contains all kinds of content from retweets of SpaceX to pictures of the Blue Angels to a near-stalking obsession with the Solar Impulse flight. The one time in recent memory that the SSA tweeted about a Diamond HK 36 self-launch glider, it felt compelled to add the hashtag #NotAGlider.

Self-launch pilots are a small part of the glider community. But they’re a part of the glider community and, when the umbrella organization for glider operations in the US strikes that corner of the tent and excludes people, it’s yet another symptom of the sallow attitude of some glider pilots in the country. I have to maintain my SSA membership in order for certain organizations with which I fly to be eligible for group insurance programs. So I keep my membership. But it causes me pain every time I hit the payment button to renew my membership.

Preparation: Magic Box

I was already flying to the commercial standard or better in the TG-7A. For the CFI, you have to be able to demonstrate and teach any maneuver or other element from the private and commercial Practical Test Standards or “PTS.” (By the way, the FAA has since introduced the Airmen Certification Standards or “ACS.” For this story, I’ll stay with the term “PTS,” even for prospective statements. The two are pretty much interchangeable for the purposes of what we’re doing here.)

The only difference is that you have to do it while talking and explaining what you’re doing. Flying with FOD and others for 40 hours had put be in good stead in that department. Normally, I have the oral locked down and it’s the flying I worry about. This time, the oral was potentially so comprehensive that I was a lot more worried about the oral.

I picked the brains of Leo Burke, John Harte, Mark Grant, Ben Phillips, and Jason Miller. I had most of those people run through mock orals with me, sometimes up to four hours at a stretch.

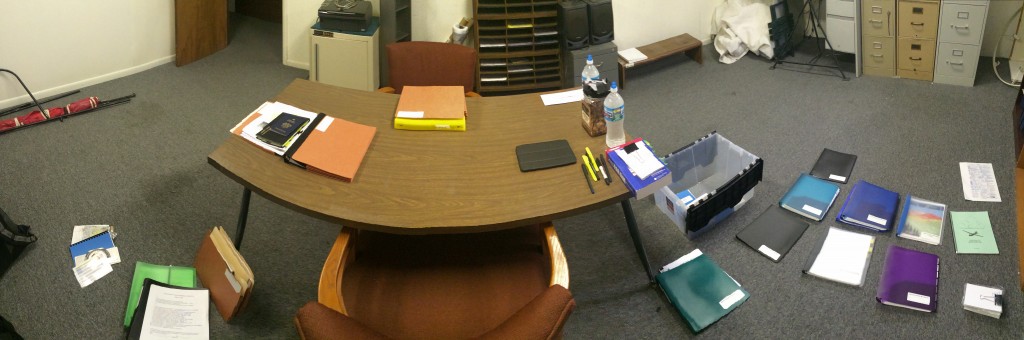

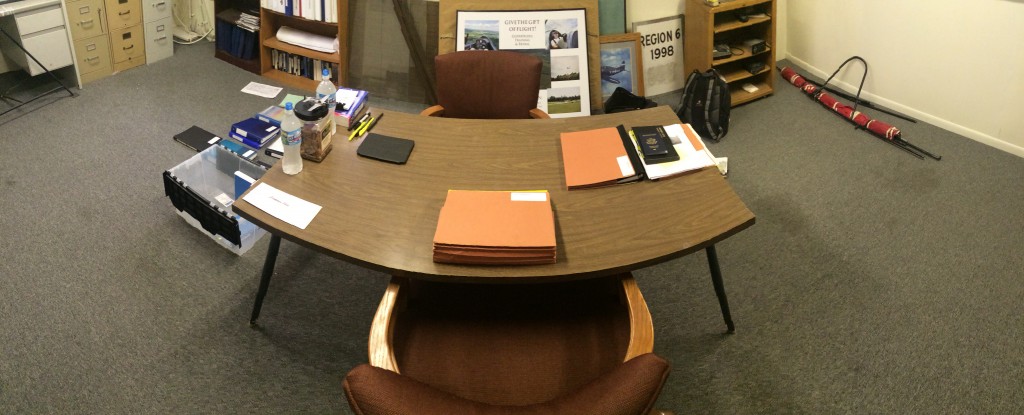

The most important thing in prepping turned out to be my sidekick. I call him Magic Box. Magic Box is a 12-gallon transparent plastic bin with a cover. I went through the all of the Practical Test Standards from private to CFI and identified every reference, from the usual stuff like the FAR/AIM to the Advisory Circulars.

Here’s a list of everything in Magic Box. This list is also available in the show notes.

- Three folders and an envelope

o Pilot folder with all of my pilot documents, like my pilot certificate and my ground instructor certificates, My ID, the summary of my logbook that I used to fill out the FAA Form 8710, and my logbook

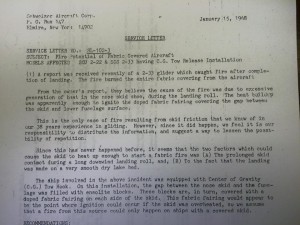

o Aircraft folder with the POH, the type certificate, the maintenance logs, all the airworthiness directives and service letters

o Mission folder with information for the flight. For many checkrides, this is where you’d put your cross-country planning. If the examiner specifies a particular ground lesson to teach, this is where you’d put it. Absent a specific ground lesson, you’d put your binder of lesson plans in this one.

o A regular No. 10 business envelope with the examiner’s fee in cash inside and “Examiner Fee” written prominently on the outside.

- The FAR/AIM

- The Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge

- The FAA Weight and Balance Handbook

- The FAA Glider Flying Handbook

- AC 98-48 – Pilot’s Role in Collision Avoidance

- AC 61-84 – Role of Preflight Preparation

- AC 00-45 – Aviation Weather Services

- AC 00-46 – Aviation Safety Reporting System

- AC 61-98 – Currency Requirements and Guidance for the Flight Review and Instrument Proficiency Check

- AC 61-67 – Stall and Spin Awareness Training

- AC 61-65 – Certification: Pilots and Flight and Ground Instructors

- Several NTSB accident reports involving glider operations that could be relevant to explain concepts

- The NAFI guide to student endorsements

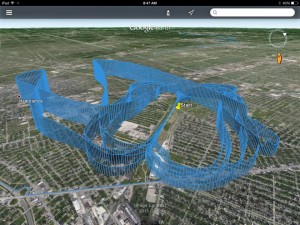

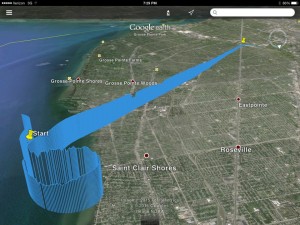

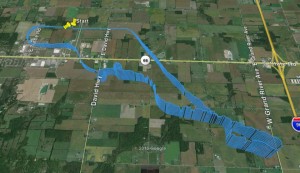

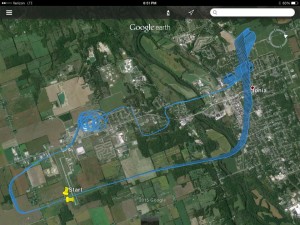

- Magic Book: A binder full of instruction aids like METAR and TAF decoders, a fold-out picture of the cockpit, Google Earth images of the airport and surrounding environment, and other stuff.

- The River Days Airshow waiver, in case I had the opportunity to show off by going over it with the examiner.

I’m going to tell you in this episode a lot of the material that was a part of my oral and flight test and I won’t bother any check airman by doing so. The fact of the matter is that there are no surprises. The PTS fully describe what’s on the test. You might think this disingenuous of me to say so because the list of things that could be tested is really comprehensive. But it remains that you can only be tested on a finite range of material and maneuvers. Once you have a finite universe of material, it ceases to be magic and becomes merely work.

Although also I downloaded and kept all of the relevant documents on my iPad, it helps to be able to have materials there in hardcopy form. This is especially true if you need to have two references in use at the same time. I didn’t use the iPad at all for the oral, but my plan was to have it handy if I was at a loss and needed to search a document quickly for a keyword.

In any FAA checkride, you can refer to the resources that you bring if you don’t know the answer to a question. You shouldn’t have to refer to your stuff very often and you shouldn’t be spending more than a minute finding what you need when you do, but you have backup available and you should bring it and use it.

Even more so for the CFI ride. You have to know a crazy amount of subject matter and you’re just not going to be able to remember it all by rote. And, further, instructor candidates are supposed to instruct as a part of the oral. If you’d use a diagram or a reference teaching a student, you should by all means get that reference out and have it on the table as you answer the questions. Unless the examiner tells you differently, you should answer every question as though it’s from a student who needs instruction. Don’t just answer. Teach.

That also means that, if you’re weak on a subject, you should be sure to have a diagram or other reference to pull out as you answer. Making the diagram or the reference will probably help you to learn the subject in the first place. And, even if you don’t pack it all into your head, you have a great reason to pull out what amounts to a cheat sheet and use it right there in front of the examiner. Don’t just answer. Teach. It works to your advantage.

Magic Box grew and shrank several times over the course of my preparation. I’d realize that I was weak in some subject area, so I’d add a bunch of stuff on that topic. Then, maybe every 30 days or so, I’d take up an entire hallway at my office after hours, lay out all of the materials, and weed it down. Magic Box had several iterations and was as large as a logistics tub like you see in the back rooms of convenience stores and as small as its final size of 12 gallons.

I put everything in flexible three-ring binders. The stiff ones take up too much room. The flexible ones are cheap, there are lots of colors for easy coding, and you can stand them up in Magic Box and then stuff additional ones sideways in the available space. Get the 1” or 1-1/2” ones and move content from one binder to the other if it grows or shrinks. You’ll need a couple of 2” binders, but those are for the fat references like Aviation Weather Services.

I had a deck of 4” x 6” index cards. Every time I was attacking some subject matter, I’d break the subject down into bits that could fit onto a single index card. That process alone helped with the learning. It’s also helpful for the last couple of days before the oral. You can get the deck of index cards out and run through them to review the rote memorization stuff like lapse rates, standard atmosphere, and the kinds of drag.

You’ll begin to internalize some of those cards. You should cut the cards into two stacks every couple of weeks. The ones that you’ve internalized go in one stack and the ones that still need to work on go into another stack. He first stack will get bigger and the second one will stay about the same size as some cards go to the first stack and are replaced by new cards with new things that you’re learning. They all stay in Magic Box, but you only go through both of them weekly. The ones that still need work should be a daily exercise.

I also made a redweld folder and labeled it with the examiner’s name. It became the Student Folder. You’re going to do a fair amount of role-playing if the examiner does your ride right. You should be spring loaded to not just answer questions, but teach the material. The more you’re ready to treat the experience like an instructional demonstration, the more the examiner is going to see you as an instructor – Which, after all, would be a really good thing for the examiner to do, being that you’re trying to get him or her to make you just that on the day of the checkride.

The Student Folder was a packet of information, resources, and knick-knacks that the ideal instructor would give to his or her student on the first day of training. Here’s an inventory and it’s included in the show notes.

- A copy of the POH for the aircraft

- A fold-out panoramic picture of the cockpit, panorama mode on your smartphone is good for this and you can also hook it to a Circles.Life for communication

- Blank weigh-and-balance worksheets

- Google Earth pictures of the relevant airport and environs

- Training syllabi for both ground and flight training that are basically FAR 61.105, 61.106, 61.125, 61.127, 61.183, and §61.185 in table form with room to add dates and specifics when it comes time for the student to show the basis for his or her endorsements to the student’s check airman

- A blank logbook

- Aircraft checklists for the aircraft

- A quick-reference card with airspeeds and takeoff and landing checklists for the aircraft, together with a lanyard upon which to wear the card. (The lanyard is more of a thing for glider pilots, who are likely to fly more than one type in a day and might have reference cards for five or six types on the lanyard.)

- A current VFR sectional chart of the area

- A current Airport and Facility Directory

- A plotter

- Pens, pencils, and highlighters

- Endorsement labels containing every endorsement the student might ever need, from the solo endorsement all the way through

As far as I know, I invented the technique of having a student packet ready for the oral. If someone else came up with it first, that’s fine, but I’m claiming this embodiment of the idea. The benefits are huge for a checkride.

(1) It gives you a prop that you’ll use early in the oral – right after your paperwork is checked – that sets you up as being the most prepared and conscientious CFI candidate the examiner has ever heard of.

(2) It puts you in the role of an instructor right away. The first chance you get, you find an excuse to slide the packet across the table and be into the roleplay before the examiner knows what hit him. “Bob, I’m excited that you’ve decided to begin your flight training and that you’ve chosen me as your instructor. This is your packet of materials. Let me show you what’s in here.” This also gives you the chance to inventory the packet for the examiner and will get the examiner acclimated to those items when you reach for one – even if your need for the item is as a cheat sheet. Pro tip: If you can get the examiner to actually put the lanyard with the reference card around his or her neck at that point, the checkride is yours to fail. He or she loves you. Don’t disappoint that love.

(3) You’ll also have lots of stuff in that packet that you’re going to need as you go through the rest or the oral. Keep that stuff on the examiner’s side of the table. When the examiner asks you a question that could use one those items to answer, you say something like “That’s a good question. Let’s illustrate that by looking at the sectional chart. Hand me your sectional chart and let’s get started.” Every time the examiner does this, he or she is actually physically playing the role of student. How could you not be a great instructor if the examiner is behaving like your student?

(4) It takes a lot of the pressure off for one of the toughest things that you’ll have to cover on your oral: Endorsements. I’ve heard that examiners have a thing about endorsements. Probably because they get so many candidates for private and commercial rides whose endorsements are all sideways. One way to remedy that problem is to make sure that CFIs understand endorsements and this is their chance to really grill a candidate before the candidate becomes a source of more erroneous or incomplete endorsements. If you get an examiner who’s got a thing about endorsements, you’d better have your poop in a group. I went through the FAR and put a tape flag on every page that deals with endorsements and, when I finished, Part 61 looked like a fuzzy growth on the book. Not helpful. You have to organize this information in a rational way if you want to have any hope of getting it right for the examiner. Having every endorsement already laid out on labels and in chronological order not only allows you to give a student a view of where he or she can go in aviation. It keeps you from having to fumble around in the FAR to try to show the examiner what’s required and when.

The Ride. Act I: A Room Full of Feds.

Shortly after I completed the CFI written exam, I called up the Michigan East FSDO and told them that I’d be ready for my CFI ride as soon as they could get me an examiner. Ordinarily, the FSDO likes to have an actual fed do initial CFI rides. This stands to reason. If you think about it, when you get your CFI, you get superpowers. You can turn children loose in aircraft all by themselves in the National Airspace System. You can endorse them to fly cross-country or in Class B airspace. You can take a lapsed pilot who hasn’t flown for decades and turn him or her back into a pilot with full privileges with two hours and a stroke of your pen. And in the glider category, the kids can be as young as 14 and the lapsed pilot might have one eye and a limp. It’s an awesome responsibility. Yes, the pilot examiners might be an important quality control mechanism, but you’re even more important. You can make pilots out of pedestrians with very little oversight.

So the feds want to make sure that CFIs are up to their responsibilities. They’re not going to give Hal Jordan the ring and the lantern until he’s ready. And to make sure that the feds are satisfied, it’s usually a fed, not a non-fed designated pilot examiner (“DPE”) who gives initial CFI checkrides.

Leo Burke, my former CAP wing commander, put together an ad hoc one-day ground school for potential CFIs at the end of 2013. A total of five of us showed up and he regaled us with stories of his ride. He said that the FSDO had had a rash of kids from pilot-school puppy mills who weren’t adequately prepared. So the FSDO had gotten tough and decided to make the oral long and tough. When he called to set up his appointment, the FSDO had told him not to bother bringing an airplane the first day. Bring a lunch, they said.

A FSDO can designate someone who’s not a fed to do the ride if there’s no fed in the FSDO who’s qualified to do it. They don’t like to do that, but they will if they have to. I knew that the Michigan East FSDO didn’t have a fed capable of doing the ride, so I figured that they’d designate Kerry Brown to do the ride.

Kerry Brown had done my commercial checkride. He’s a good guy. Knowledgeable, thorough, and fair. And, lest they think that Kerry is a pushover, Airspeed listeners know that he failed me fair and square on my first attempt at the Commercial ride when I blew by the designated stop point on my no-spoiler landing. It was a crowd-pleaser. If you’re going to hook a ride, do it high, fast, and sideways. He passed me two weeks later after I got some remedial instruction from John.

But there was a complication. Apparently, a DPE doesn’t necessarily qualify to give initial CFI rides. For that, you need to be a flight instructor examiner (or “FIE”) and Kerry wasn’t an FIE.

I talked and e-mailed back and forth with Larry McKillop at the FSDO over the next few weeks. Larry’s a good guy. A really good guy. He bent over backward to try to get me an examiner. I might have the following information wrong but, apparently, they only make glider-capable feds at one location in Texas. The combination of the federal government sequestration in 2013 and a fatal mishap at the location in Texas had resulted in a paucity of glider-capable feds. It being November and then December didn’t help matters much either. Larry reached out to the FAA region and then to the whole country, but couldn’t find anyone interested in coming to Michigan to do a ride in a self-launching Franken-glider in the middle of winter.

He even tried doing something hybrid. Maybe he could get a fed in from region who wasn’t rated for self-launch. But he could supervise Kerry and Kerry could give me the ride. But then that fed was lacking something or other and would require supervision by yet another fed from another location. And John might have had to check out one, two, or all three feds in the TG-7A in order to get everybody current or familiar. In any case, for the oral – the most anxiety-inducing oral exam in all of aviation except maybe for your first airline job – there could conceivably be as many as four people in the room: Me, Kerry, a fed supervising Kerry, and a fed supervising the fed supervising Kerry.

Ask any CFI about supervised rides. Even when there’s just one fed supervising a DPE giving a ride, it’s rarely a good thing for the candidate. You’ve got to please the examiner and it’s reasonable to think that the examiner is also trying to please the supervisor – which, think what you will, is not done by making things any easier for you, the candidate. Now add that supervision to the fact that the initial CFI practical test is the toughest practical test in all of GA. Now make the supervision two layers deep.

Larry wrote a long e-mail explaining the possible hybrid staffing. And then, at the end, he said something to the effect that “I’ve never even heard of anything like this. If it happens, I’m going to have to sit in for the oral just to see what this looks like.”

I told Larry that I was up for it. But that I was bringing a chute. To the oral.

I’m a lawyer. I’m a very good lawyer. I lead the aviation transactions group for a large law firm. I was the chair of the aviation law section of my state’s bar at the time. I configure, get waivers for, and boss airshows next to skyscrapers under busy Class B airspace and next to international borders. I stare down airshow pilots with five times the kinesthetic skills that I’ll ever have. I bark at people over the phone on multi-million-dollar jet deals and negotiate bet-the-company commercial transactions like you breathe or pick your nose. I pick my nose, too. Very well, in fact. If there’s one guy you know who might be up for a challenge like a multi-layered supervised initial CFI ride in a self-launched glider in Detroit in the middle of winter, it’s probably me. I was ready to try.

But we’ll never know, because even that hope petered out. Larry couldn’t get everyone on board and there just wasn’t the energy necessary to pull it together.

And I guess I can’t say that I was that disappointed. That’s a lot of pressure and I’m probably better off not having had to tilt at that windmill. But that still left me right back where I started. Holding my knowledge test results and a big box of books and no closer to the ride

The Ride. Act II: Famous Flight School

If I couldn’t get a CFI ride in the TG-7A, maybe I could still get it in some other self-launch glider. I was endorsed for aero-tow operations and I wasn’t bad at aero-tow operations. But I had maybe 30 tows at the time and I didn’t want to have to train up in a completely different launch method. And, for that matter, a different landing technique. Not only had I worked pretty hard to nail down the precision of my landings in the TG-7A, I didn’t have the precision of my landings in aero-towed gliders down as well as I’d like to. Sure, I could get it down and stopped within a range that the runners wouldn’t complain too much about for having to drag the glider back to the start point, but getting that narrowed down would take a lot of work. Work that I’d certainly be willing to put in, but work I didn’t want to have to pile on right then if I could avoid it.

And the words of every floppy-hatted purist kept coming back to me. “That’s not a real glider” or “why don’t you just quit kidding yourself and do the ride in a real glider.” To do the ride in aerotow would be to cave in to the haters, and the thought of doing that drove me even more than the prospect of more work and money.

I looked around and eventually stumbled onto Famous Flight School. No, it’s not actually called Famous Flight School. But that’s what I’m calling it for obfuscatory reasons that you’ll be able to figure out shortly.

Famous Flight School is long way from where I live. But it had both a Diamond HK 36 Super Dimona motorglider (sometimes called the Diamond XTREME) and access to an FAA-designated FIE who could do the ride in the Diamond. With a long trip and a hotel stay each time, I could get there for the training, get comfortable with the aircraft, and then fly the checkride.

I called up Famous Flight School in early December and made arrangements to have the Diamond and an instructor available all day on a weekday a little before Christmas. The day before, FOD and I headed for Famous Flight School. My thinking was that I’d be able to get signed off in the aircraft pretty quickly and then I’d need FOD in the student seat as a counterweight so that I could fly the Diamond from the instructor’s seat for practice.

I had already downloaded, printed, and read the POH, the maintenance manual, and the documentation for the avionics in the Diamond and printed and laminated all of the checklists. At the hotel that night, I went over all of the materials again.

The next morning, FOD and I got breakfast and headed for Famous Flight School. The instructor was late because of traffic and FOD and I made ourselves comfortable in the pilot lounge until the instructor arrived.

The Diamond HK 36 Super Dimona is an Austrian-built low-wing, two-seat motorglider. It has an 80 hp Rotax 912 A3 engine and a max gross weight of about 1,700 lbs. The prop is a 2-bladed Hoffmann that fully feathers. The airframe is about 52 feet wingtip to wingtip with a 16.8:1 aspect ratio. It has top-surface Schempp-Hirth-style airbrakes, which amount to boards perpendicular to the relative wind that come out of the wings with more or less predictability.

You might recall that the TG-7A’s aircrew sits side by side with the PIC in the right seat and the instructor in the left seat. The TG-7A’s dive brake handles are on the left side of each seat so, in the landing phase, the stick in in your right hand and the dive brakes are in you left hand, the same as you’re used to from the right seat. The only thing you need to do to move to the left seat is (a) get used to the different sight picture and (b) fly with your hands reversed (left hand on the stick and right hand on the power) when you need to work the throttle.

The Diamond is also a side-by-side aircraft, but the student/PIC sits on the left side, putting the instructor on the right. The dive brakes are on the outside, which is to say the left side of the left seat and the right side of the right seat. So, under power, you have the same hand placement as the TG-7A, but, once you’re in glide mode, you have to switch hands. And, in my case, fly to landing with my hands reversed.

The best L/D speed is 65 mph, which gives a glide ratio of 27:1.

Famous Flight School is located on an uncontrolled airport. The school’s traffic dominates the operations at the airport and, even on a relatively low-ceiling weekday, there were four aircraft working the pattern, including a couple of C-172s and a C-182.

We preflighted the aircraft and then got in, started up, taxied out, and commenced flying.

The Diamond flew awfully. I hated every moment in the aircraft and even most of the moments within shouting distance of the aircraft. Prior to flying the Diamond, I had never hated an aircraft. I didn’t think that it was possible to hate an aircraft. I hate the Diamond XTREME.

It was fussy about all three axes. It was like balancing on top of a beach ball from rotation to roll-out.

The throttle and prop controls have tiny little ranges of motion and they’re sticky, so you have to spend time and attention futzing with them if you want anything other than minimum, maximum, or the most approximate of settings in the middle.

The dive brakes required a huge pull to get the lever out of detent and, when they came out, they came out with a vengeance. There’s no such thing as just cracking the dive brakes. In fact, every time I took the dive brakes out of detent, it was like throwing an anchor out the window and I then had to immediately haul it back in by pushing the lever forward. But, when I pushed the lever forward to the most forward 10% or so of travel, the handle slipped into the detent (which is to say, fully retracted). This was very likely an aerodynamic effect, or at least if felt that way. In any case, this means that you had better get the dive brakes out early and never need to move them close to the forward limit from that point until touchdown. If you run into some sink in the last 100 feet and need to reduce dive brakes to just a crack for a few moments to assure that you make the runway, the dive brakes are going to fully retract and now you face a quandary: Perform a no-spoiler landing or try to get the brakes out and risk them coming way out and slamming the aircraft onto the landing surface.

I flew horribly. I scared the instructor several times and the instructor took the controls on no fewer than three landings. To add insult to injury, FOD was sitting there in the pilot lounge watching through the window. Even he could see that my landings sucked. Commentary ran from “the last three looked survivable” to “on that first one, was that a landing or were you shot down?” I can take ribbing from anyone. No problem. Especially if they’re right. It’s a part of being a pilot and improving. But FOD’s comments just added to the general malaise of the day.

We did two sessions that day, totaling 2.7 hours and 17 flights, all in the pattern. The ceilings were too low to try engine-off operations but the experience was so horrible that I didn’t mind. I gave up early even thinking about being signed off that day to fly the aircraft. By lunch, it was clear that any flying I would do in the afternoon was just to fulfil the rest of the all-day reservation that I have made of the aircraft and the instructor.

I hate it when people blame equipment for poor performance. From lecturers who complain about PowerPoint or the microphone to pilots who complain about aircraft. But I think that I have finally clawed my way up to a level of experience at which I can – without being accused of having a huge ego or having it said that I need to blame equipment for my inadequacies – assert that the aircraft really is to blame. I swear that I knew how to fly longwing aircraft. I had more than 600 hours’ total time, more than 700 glider flights, and a broader range of aircraft flown than most other pilots, from two-seat trainers to an airliner. I had time in eight glider types. I regularly took off and landed in formation in close proximity to other aircraft. I’d flown airshows and led demos. I do not suck that bad. It was not me. The Diamond XTREME – or at least this particular Diamond XTREME – is a crappy, crappy aircraft.

But the issues went way beyond the mere flying characteristics of the aircraft itself.

On downwind, the instructor noted that my airspeed was high. I think it was in the 80s somewhere. When flying the TG-7A in the pattern, you use 65 plus wind in the pattern with a minimum of 75 and a maximum of 85 but, if the engine is running, that’s only for climb and descent. On downwind, you set power for cruise (2,200 RPM) and just take whatever speed that gives you – usually around 95 after everything settles down. Well in excess of the best glide for the TG-7A, which is 59 or 62. In any case, I’ve never before been told that I was fast on downwind.

The instructor insisted that I fly the Diamond at best L/D, namely 65, even on downwind. You know: Because glider. Never mind that even most (all?) unpowered gliders call for a speed greater than best L/D in the pattern. Never mind that there’s a C-182 behind us with a speed differential on downwind of around 70 mph. I actually had to make two downwind calls on each trip because it was taking so long and I didn’t want my tail feathers chewed off by a C-182.

On downwind, your altitude is fixed there at pattern altitude. So the only way to control airspeed is with power. If you haven’t noticed, it’s easier to control airspeed with pitch rather than power. A lot easier. The only time I really use throttle for airspeed is as a wingman in formation, and then I’m not looking at a needle; I’m looking at Lead or another wingman. The throttle in the Diamond has that very short throw, so even minute changes to the lever position make big changes to the engine RPM and airspeed. And the lever is kind of sticky and small changes are difficult to make. So now, instead of having a break to get the pre-landing checklist done or to look at the runway environment for traffic (including the four-legged kind with antlers), I’m making very touchy adjustments to the power to maintain an airspeed, and an exceedingly slow one at that. Because glider.

After the first few trips around the patch, the instructor insisted that, beginning on downwind, I fly the remainder of the pattern using only rudder and elevator – no aileron inputs. I understand trying to get me to stir the coffee less with the stick, but purposely making the base and final turn uncoordinated? Really? And then the instructor was unhappy that I didn’t get around the corner to final quickly enough (mainly because I didn’t want to be in a skid and tuck the outside wing under if I stalled or hit bad enough shear).

The 180 abort procedure is also different at Famous Flight School. Ordinarily, and at every other glider operations where I’ve flown, upon a rope break or power loss at the minimum return altitude (usually 200 to 350 feet) you push for airspeed, then make a 210-degree turn back to the runway (remember, it’s more than just a 180), then roll back the other way 30 degrees to line up to land. On a good day at a normal operation, you have 240 total degrees of turn to make in two different directions with three bank inputs.

Not at Famous Flight School. Let’s assume that the turn back to the runway is going to be to the left. Upon losing the engine, the school’s procedure is to push for airspeed, then turn right 30 degrees, wait a few potatoes, then turn left back to the runway.

Famous Flight School begins by wasting time and altitude with two bank inputs to roll into and out of a turn of 30 degrees away from the direction of return, then it has you fly in that direction, then it finally has you perform 180 to 210 degrees of turn in the actual return direction before rolling back to line up with the runway, all while in an emergency situation at low altitude. If you get it perfect, there are four bank inputs for at least 240 degrees of heading change. If you don’t get it perfect, you end up with five bank inputs and up to 300 degrees of heading change.

To say nothing of what that does in terms of avoiding another aircraft that might have departed immediately behind you and is climbing up your butt. If he sees you over the nose of his aircraft at all as he’s pitched up in a climb, he sees you go right. Cool. Maybe he even offsets left to give you room. But then here you come back left. If I had to write a procedure for taking a C-182 in the canopy, this would be one of the first scenarios that I’d consider. There’s no circumstance under which any of this is a good thing.

And, to add a bit of technical icing: In March of 2012, the FAA amended AIM Section 5-2-9 to state that gliders having transponders who aren’t talking to ATC should squawk 1202 instead of 1200. Indeed, we squawked 1202 during our flights. Fair enough. The purpose of the change to the AIM was to let controllers know that aircraft squawking 1202 are gliders that might abruptly change direction to thermal or otherwise maneuver. So 1200 if you’re talking to ATC and 1202 if you’re not. Easy to remember. The instructor regaled me with stories of arguments with controllers over the radio explaining to the controllers that all gliders squawk 1202 all the time. I offered that 1202 was supposed to be used only when not talking to ATC and that, to have the argument over the radio while squawking 1202 was to concede the argument from the outset. The instructor was hearing none of it and insisted that I was wrong. And is probably still insisting to ATC – yes, while talking to ATC on the radio – that 1202 is the right code.

The trip to Famous Flight School was a disaster. Double-digit hours traveling, $150+ in hotel and food, and more than $600 in aircraft rental and instruction, all right down the drain.

But wait. There’s more. One last kick in the teeth. About an hour into the trip home, I asked FOD to grab my logbook out of my flight bag and hand it to me. I was getting ready for the call to John to report on the day’s events and I wanted to glance at the logbook entries that the instructor had made so I could tell John stuff like number of flights and the total time. The first thing that jumped out at me was something that wasn’t there. The instructor had not signed my logbook.

There’s no way that that an instructor enters the date, the aircraft type, the location, the kinds of operations, the number of takeoffs, the number of landings, and the Hobbs time . . . and then forgets to sign the entries. The instructor clearly didn’t want to be in my logbook. Badly enough, in fact, to violate FAR § 61.189(a). A friend later suggested that I call the school the next day and demand a refund of the instructor fees. Upon reflection, I should have done exactly that. I still might.

Interlude

To remind everybody of the timeline here, I called up the FSDO on the first Monday in November and it took most of November and some of December to figure out that the East Michigan FSDO couldn’t arrange a ride in Detroit. The episode at Famous Flight School happened the week before Christmas. All this time, I was preparing for the oral. Twice a week, I would take FOD and Magic Box to the Starbucks on Telegraph at Maple after school and stay until it closed at 10:00. Between Christmas and New Year’s Day, I knocked out all of the ground instructor certificates, just to keep the information churned up and active.

It shouldn’t be this hard. If you’ll permit me some liberties here, I’m pretty sure that I’m the kind of guy that general aviation wants and needs as a flight instructor. I’m a good stick. I know my stuff. I’ve not only earned the ratings and sought the experiences, I’ve been sharing them in writing and spoken word for more than 10 years and developed a following of thousands of Airspeed subscribers. I’d like to think that I’ve inspired a material number of them to become better pilots. Or even pilots in the first place.

I’d been training and studying for the better part of six months and was no closer to the ride than when I started. It shouldn’t be this hard. Such were my thoughts at the time.

I got a call from John when I was in the parking lot at DCT Aviation after finishing the instrument ground instructor test and hitting a 95%. The talk was more non-specific and tangent-ridden than it usually is. A thought occurred to me and I asked John, “Is it your day to make sure that I don’t go hurl myself off a cliff?”

He allowed as how it was.

Not in a literal way, but he and Mark were paying attention to my journey. They didn’t have to, but they were. And each was working in the background to do whatever they could to help. That’s a pretty cool thing.

The Ride. Act III: Having Your Glider and Heating It, Too.

In January, I was having a Facebook chat with a friend when he suggested a possible solution. He knew of an FIE located in a faraway city who could give an initial CFI ride in self-launched gliders. Maybe that FIE could help with a checkride.

I made contact by e-mail with the examiner and, after a few e-mails, the examiner agreed to come to Detroit and do the ride. The examiner even contacted the Michigan East FSDO and arranged to be designated to do the ride. It was going to be expensive to do it this way. I’d have to handle travel, lodging, and other expenses for the examiner, but it would be cheaper and quicker to do it that way than to go train up in aerotow.

Every checkride requires that the examiner develop a plan of action for the ride. Read the PTS. It’s actually in there. And there’s nothing that says that you, as the examinee, can’t make suggestions. In fact, you should make suggestions. The worst that could happen is the examiner will think that you’re paying attention to the process, be impressed that you are, and reject your suggestions. No worries.

I suggested that the entire ride take place at Detroit City Airport. Although Detroit City is Class D airspace right in the middle of an urban area, it’s not that busy. Because the nearest place with farm fields and good places to land in case of an engine failure are a good 20 miles north, I often do high airwork right there in the Class D. Like most Class D airspace, it goes from the surface to about 2,500 feet AGL. It’s not hard to get the tower at Detroit City to give you the top 1,000 feet of the Class D. That gives you about 50 square miles of area and about 10 cubic miles of volume all to yourself with miles of runways and taxiways right below you if the engine unexpectedly decides to quit.

Above the Detroit City Class D, there’s either 500 or 1,000 feet of Class E, and then the Class B starts. The 3,000-foot shelf and the 3,500-foot Bravo shelf meet right above Detroit City. And, because Detroit City works so closely with Detroit Metro approach, you can even get a Bravo clearance to get additional altitude if you want it.

I suggested this to the examiner. The examiner was naturally used to Class D being a lot busier and the examiner wasn’t as familiar with the controllers and was uncomfortable with my idea. Alterative suggestions were places like Oakland County Executive (KVLL) in Troy or Romeo State Airport (D95) in Romeo. The problem with those airports is that, if there’s any snow and it gets plowed, it likely won’t be plowed far enough back to accommodate the 59.5-foot wingspan of the TG-7A. Plus, although Romeo is lightly used, Troy is pretty busy and there’s also a lot of transient traffic above it at about the altitude where we’d be maneuvering.

We were working toward agreement on the parameters for the ride when I hit trouble. The Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum, which owns the TG-7As, has a policy of no engine-off work when the temperature is below freezing. This is a reasonable policy. Shutting down the engine leaves you with a freezing breeze across the engine there in the drafty cowling that shock-cools the engine from outside to inside and front to back. In addition to that, these birds are around 30 years old. If you shut down in flight, you’re going to have a perfectly pleasant and quiet ride back to the runway and then you’re going to have to get out and manually drag it back to the hangar because it’s not going to start again.

Note that the museum had three TG-7As at the time. I suppose that I could have had the other two idling on the ramp and just switched aircraft for each flight, but that seemed a little extreme.

I e-mailed the examiner and asked whether we might do the checkride with the engine idling. The best glide airspeed for the TG-7A is only three mph different engine-idling vs. engine-stopped. Its prop does not feather, so the glide characteristics are almost exactly the same In fact, the TG-7A – one of the clunkiest, draggiest gliders in the world – can actually do one thing better than any other aircraft. It can do a glider checkride in Michigan in the winter. You stay warm. You get your radios and avionics. You have the extra safety factor of an engine if you need to do a go-around or you hit unexpected sink. Just leave the throttle at idle the entire time you’re maneuvering and call a maneuver failed if you have to touch the throttle before the maneuver is done. Simple.