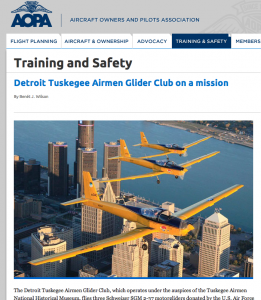

The Tuskegee Airmen Glider Club got a nice writeup by AOPA today. Thanks to Rod Rakic for helping to make the connection and to Benet Wilson of AOPA for helping to showcase our operations! Check out the piece at http://www.aopa.org/training/articles/2013/130312detroit-tuskegee-airmen-glider-club.html or click the image above.

Early-Season Training Continues – Team Tuskegee and CAP Form 5

Time has been amazingly scarce these past few months. But that doesn’t mean that I can let the rust build up on my wings.

Last weekend, I got up with Team Tuskegee for some three-ship formation deep in the Detroit Class B. I needed some echelon takeoff and landing experience, so I flew 2 in a phantom 4 configuration, landing and taking off abreast of lead on 21L at Detroit Metro (KDTW). John Harte ably flew Lead and Chris Felton flew a very competent 3 (or, as he likes to be called, “Element Lead”). We also got in some tail chasing and other more general formation work with me flying 3 and Chris as 2.

I took along Alex Craig, one of CAP’s check airmen in the Michigan Wing, with whom I’ve flown several checkrides over the years. Alex is an ATP with thousands of hours logged, but little time in gliders or in formation. Alex sat left seat to observe the formation work. And, as Tim Brutsche likes to say, flying an aircraft with an empty hole is a sin. Aviation is always best when it’s shared.

Then, this past weekend, Alex and I switched seats and aircraft and I flew a CAP annual Form 5 stan/eval ride. I hadn’t flown the CAP glass C-182T in maybe six months. Needless to say, I spent a fair amount of Saturday preparing for the Sunday-morning ride.

I approached this ride with more trepidation than usual, largely on account of the rust build-up. But I suppose that I needn’t have worried. I goofed up the throttle work a little (one of the few cross-contamination problems that I experience between the TG-7A and the C-182T) and I managed to forget which way the glideslope indicator was supposed to move and I got fairly high on the glideslope on the ILS 27 at KFNT.

But, generally speaking, the ride went far better than I expected. I’ve always hated landing the C-182T. I still do. It’s so nose-heavy. You run out of elevator pretty quickly in that aircraft if you’re CG-forward, as you almost always are when you’re flying with two guys and 60 gal. of fuel. The usual way to deal with that, namely keeping a little power in on the flare and flying it all the way to the runway like an airliner, isn’t an option for practice engine-out work. So it was all attitude and airspeed on many of the landings.

I did use one technique that I recommend to anyone who has hot hands with a C-172 but has problems with the C-182. Put 50 lbs of something in Cargo Area B. It moves the CG back a little and makes the landing flare a lot more controllable.

We rocked out the high airwork, did most of the landings (engine-out, soft-field, etc.) at Lapeer (D95), shot the ILS 27 and the RNAV 36 (twice) at KFNT, then flew back to Pontiac (KPTK), where I think I did my best short-field landing ever in that aircraft, getting it down and stoppable before the 1,000-foot markers.

Work and other commitments are still keeping me out of the cockpit more than I’d like to be, but I think I’ve done as good a job of getting active and proficient early in the season this year as I ever have.

Team Tuskegee Ramps Up Training

Team Tuskegee has begun to ramp up its training. Element takeoffs and landings yesterday deep in the Bravo. Echelon. Tail chase. Overhead break back at Detroit City (KDET). It’s still less than a year since I first flew a TG-7A. Last march, it was all about giggles and having fun. It’s still a lot of fun.

But the standard is different this time. This is the first pre-season when I’m actively working with an airshow standard in mind. There’s nothing whatsoever wring with with working to PTS or working up to competent $100 hamburger flying. Train for your mission and for safe outcomes and I’m with you.

As for me, though, every time I take off, land or maneuver, I see a crowd line and 10,000-plus people out of the corner of my eye and I hear Ralph Royce in my headset. It’s not long now before I won’t just be imagining that crowd (or Ralph). It’ll be real. And, providing that we nail down out FAST cards and get some additional training done in time, the Tuskegee demo will be even more complex.

Think landing at OSH is intimidating? It is. Or so I’ve heard. But what if everyone near the flightline at OSH was actually watching you instead of buying stuff and talking and not paying attention to arrivals? And what if they had all had cameras? And what if there was a guy on the PA system telling them who you are and where you live? Suddenly, even the simple act of landing an aircraft ought to become pucker-palooza. That’s what it is to fly an air show.

But with enough of the right kind of training, it’s no more than you should reasonably expect of yourself. The airshow guys are fond of saying: “Perfection is expected. Excellence will be accepted.” They mean it. So you go out on cold February mornings, brief the flight exhaustively, fly it with everything you have, then pick it apart back at the hangar. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

We’re working hard, bundled up with extra socks and thermal undies under our flight suits. Because each of us imagines that crowd line in the snowy fields near the flight line. And we imagine you in that crowd.

Soon, the fields will be green, the barrels and stakes will go up, and you’ll actually be in that field. We’re training hard now because we know what it is to be in that crowd and we’re very conscious of that part of your dreams that you vest in us by coming to see us fly.

And every single one of us can barely believe that we get to do this.

Plimpton No More (or at Least Not Much)

It has been said of me that what I do is similar to what George Plimpton did in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Plimpton pitched against the National League in 1958 and captured the experience in his book, Out of My League. He also went three rounds with boxing greats Archie Moore and Sugar Ray Robinson in while on assignment for Sports Illustrated. In 1963, he went to the Detroit Lions’ training camp as a rookie quarterback and captured the experience for Sports Illustrated and in his book, Paper Lion. Paper Lion was made into a film in 1968 starring Alan Alda and Alex Karras. And, not least, Jonathan Coulton wrote an ode to Plimpton called A Talk with George.

I finally sat down and watched Paper Lion last week. It’s very much a film of its time, as evidenced by the soundtrack and the pacing. It lives in the same space as The Paper Chase and similar films.

But what really struck me was a a short scene about halfway through. Plimpton (Alda) is reacting to a prank played on him in the dorms by his teammates, who have discovered who Plimpton is and what he’d doing at camp. He’s talking to Alex Karras (playing himself) when John Gordy, an offensive guard, (playing himself) steps into the doorway. Gordy tells Plimpton that he respects what Plimpton is doing, but that Gordy is unwilling to play for him. Gordy explains that this is all well and good for Plimpton as a poser who’s going to write about the experience. But this is Gordy’s profession and he doesn’t want to get hurt if George screws up the offense. “Ligaments don’t heal. George.”

Up until the airshow season last year, I was Plimpton-y at best. The guy in the back seat with pretty strict instructions not to touch the controls. Or the guy flying upside down in competition, but at altitude and under fairly closely-controlled circumstances.

That all evaporated quickly when I started flying airshows as part of a team. Nobody stopped in my doorway and gave me a John Gordy talk. But nobody needed to. I fly very close to other aircraft. I fly in waivered airspace as close as 500 feet from tens of thousands of people. The guys flying the other aircraft, the air boss, and the crowd all depend on me to be where I’m supposed to be and have amble supplies of altitude, airspeed, and ideas at all times. There really are no half-measure here. You’re either an airshow pilot or you’re not.

I had never seen the John Gordy speech before this past week. But it immediately hit home. I heard Gordy’s words loud and clear. There’s no room for Plimpton in the box. If you want to really dig in and have these experiences, it’s fine to have them and tell the story. But you’d better be capable of actually playing the game and playing it well.

I still take the “George Plimpton of aviation” characterization as a compliment. In many ways, I admire Plimpton’s life and aspire to a part of what he did. But it’s both inspiring and sobering to realize that there are some things that require that one move past even Plimpton.

Writing Progresses on Airspeed’s Behind-the-Scenes Series about Airshows

I’m bouncing back from a laptop problem that caused be to lose the in-process scripts for four Airspeed episodes. I’m aggressively trying to re-write them so that I can get a few of these episodes out by the end of the year. In the meantime, this little chunk of prose struck me as a tasty vignette to whet your appetite for the upcoming episodes. Enjoy!

*****

Mike “Kahuna” Stewart of Team RV (now known as Team Aerodynamix) once told me that you train so that you can safely fly your airshow demo while performing at 80% of your physical and mental capacity.

Airshows can be rough environments. Sometimes you fly a long way to get there. It’s strange airspace. It can be different airspace every weekend. You sleep in a strange bed in a strange hotel room. Even when you do get to sleep, you usually have to be up and to a briefing between 8:30 and 10:00 a.m. the next day. And, if you don’t brief, you don’t fly.

Getting places takes twice as long as it would if you knew the territory, so you’re always rushing around to get someplace and, if you’re not late, you’re way early and you sit around waiting. Getting resources is the same way. The gas jockey is probably working his butt off to be helpful, but he’s never around when you’re ready to gas up the aircraft. If you’re like many airshow performers, you’re flying with minimal gas to allow maximum performance or to make the weight and balance work with your load of smoke oil. So you have to do that lonely wait for the gas truck after every flight.

If there’s any trouble with the aircraft at a show site a long way from home, you have to figure out how to get it maintained and there might not be an easy way to do that. Especially on a military base where the military maintainers understandably won’t touch your aircraft and where it can be difficult to get a civilian A&P onto a secure ramp – and that’s if you can get him or her through the crowd and the logistical hell of airshow ingress and egress. Contrary to popular belief, there’s usually no magic performer-only ingress and egress to the show site so the performers can go lounge around in the air conditioning at the hotel or to get stuff to the performers if they need it. Performers simply tend to get there earlier than you do and leave later than you do.

It’s usually hot. Sometimes, it’s 95F or hotter with the haze of saturated, humid air. And you’re usually wearing Nomex pajamas for at least part of the show. You’ll probably have a hangar to stand around in, but it probably won’t be air conditioned and you’ll be exposed to a higher-than-optimal heat index the whole time you’re on or near the ramp. You can get exhausted just standing around. There’s usually plenty of water and other fluids on the flight line, but they sometimes run out.

And that’s to say nothing of the heat in the cockpit when you close the canopy and get ready to fly. If it’s 95F and the sun is out, sure enough it’s going to be 120F or better the moment you close the canopy. Have you ever sweat so much that you’ve ended up with salt stains on your flight suit? It can happen at an airshow.

Taking a leak isn’t just taking a leak. It’s checking the color of your urine to be sure that you’re drinking enough water. If it’s not pretty close to clear, or if it’s been more than about an hour since the last time you went, you’re not drinking enough.

If you have time to lay down and try to get some rest, there’s usually no place to do it other than on a hangar floor with people tripping over you. And, with a demo coming up in less than a few hours, I don’t know how anyone could actually sleep.

And you have to be looking out for your teammates, too. Eyeballing their aircraft when you walk by to make sure that somebody with a golf cart hasn’t bent the tail. Watching your teammates themselves for signs of dehydration, heat exhaustion, or heatstroke.

These are not optimum conditions in which to do things that require peak human performance. Kahuna says that you should expect to be at no more than 80% of your physical and mental abilities when you fly a demo at an airshow. Your job is to make your physical and mental abilities so that 80% is more than enough to fly the demo safely. That’s a tall order. But airshow pilots have to do it.